Discrimination in matters of housing has long existed in India. Finding housing can be an onerous task for anyone who doesn’t fit within the ideal of what the Hindu upper-caste imagination views as desirable and respectable. While religion, caste, gender, sexuality, marital status, linguistic background, and eating preferences all play a role in determining if people have unrestricted and equal access to housing, caste- and religion-based housing discrimination is rampant and often results in the creation of segregated living spaces and ghettos. While popular understanding of ghettos is often associated with—and limited to—rural India, this couldn’t be far from the truth; ghettoisation pervades all of India, transcending the urban-rural divide and class.

Recently, a Muslim couple was forced to sell their newly purchased house in an affluent neighbourhood of Uttar Pradesh’s Moradabad after residents of the locality protested against them moving in because of their religion. The residents staged their bigoted protests following the news of the sale going public, demanding the house be resold to Hindus. One of the protestors said, “We cannot tolerate a Muslim family living right in front of our local temple. This is also a question of the safety of our women.” She went on to brazenly say that people of other religious faiths would not be allowed to live in their neighbourhood.

Calling it a ‘Hindu society,’ the protestors alleged that only Hindu families live in their neighbourhood and that the residents had a verbal agreement that they wouldn’t sell their homes to Muslims. Raising concerns that the Muslim family moving in would lead to Hindus leaving the area and cause ‘demographic changes,’ the protestors filed a complaint with the district administration. The previous owner of the house said that the couple no longer felt comfortable moving in.

But this isn’t the first of such attempts aimed at the spatial segregation and othering of Muslims in India, or even in Moradabad. After two Muslim families bought houses in a Moradabad locality in 2021, Hindu residents of the area began to protest and threatened to sell their properties en masse if the families did not leave. As with the recent incident, concerns were raised over a local temple, with protestors claiming they needed to ‘protect,’ it. The leader of a Hindutva outfit and his aides were found to be instigating the protestors and an FIR was booked against them.

While religion and caste-based housing discrimination have always existed, how such prejudice is increasingly being brazenly vocalised and how minorities are publicly and visibly being denied their constitutional rights without consequence brings into sharper focus the realities of segregated urban living spaces and the increasing ghettoisation of Muslims.

Urban ghettoisation

While the Islamophobia displayed in Moradabad, unfortunately, may seem like the quotidian bigotry of a country infested with Hindutva’s divisive, majoritarian ideology, the broader implication of such othering of Muslims in matters of housing is the increasingly common prospect of urban ghettoisation they face.

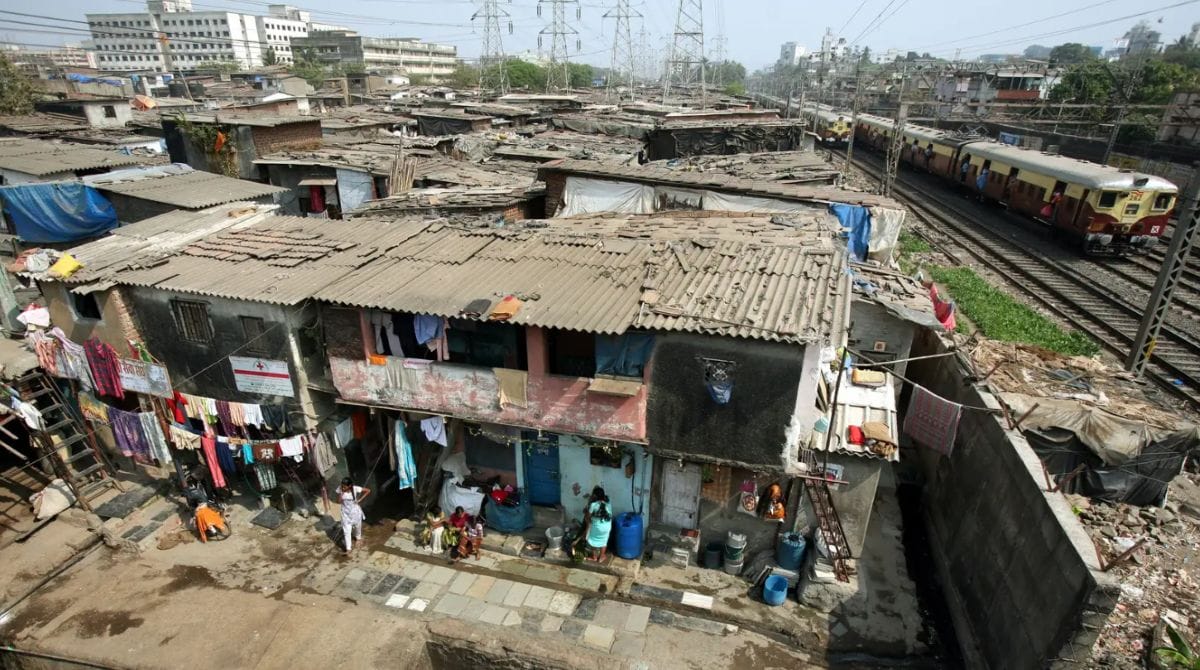

Ghettoisation is the process by which marginalised minority groups are segregated and isolated from others and relegated to living in specific, confined areas which house only members of their own community. According to French sociologist Loïc Wacquant, ghettos are an instrument for ethno-racial control and a form of collective violence. Ghettos, he posits, have four constituent characteristics: institutional encasement, confinement, constraint, and stigma.

India is no stranger to the segregation of the ‘other.’ A 2023 study, based on data from 2011-2013, found that in rural and urban spaces, spatial segregation was deeply entrenched and was on par with the levels of racial segregation in the United States. 26 per cent of Muslims and 17 per cent of Scheduled Castes were found to be living in neighbourhoods where more than 80 per cent of residents were from their religious and caste group, respectively.

But as Hindutva draws more zealots into its fold and an environment of majoritarianism suffuses, open calls for and attempts at the spatial segregation of Muslims are on the rise. In Gujarat’s Vadodara, a Muslim woman was allotted a flat under the Mukhyamantri Awas Yojna; but before she could move in, residents broke into a protest and complained to the administration, demanding the allotment be invalidated due to her faith. The memorandum by the housing society read, “We believe that Harni area is a Hindu-dominated peaceful area and there is no settlement of Muslims in the periphery of about four kilometres… It is like setting fire to the peaceful life of 461 families.”

Beyond social marginalisation and lack of development

Social marginalisation, limited economic opportunities, and lack of development are salient consequences of ghettoisation, but its effects go beyond just social ostracisation or state neglect. For one, such segregation makes minorities vulnerable to various forms of majoritarian coercion and violence. Ghettos not only make minorities more vulnerable to communal violence due to easy identification and the dense concentration in one area, but this concentration also makes targeted state surveillance of Muslims not only possible but feasible.

In Hyderabad, since 2015, a majority of cordon-and-search operations have disproportionately been conducted in Muslim-majority areas. In Delhi, a 2021 research found that it is inevitable that surveillance using Facial Recognition Technology (FRT) will disproportionately impact Muslims due to the over-policing of Muslim-majority areas in Delhi (it’s undetermined if such over-policing is arbitrary or by design). Surveillance is a component of confinement (one of the four constituent features of ghettos) as per Wacquant. Confinement can be physical (like the high walls of Ahmedabad’s Juhapura ghetto) or it can be in the form of state surveillance and over-policing.

Surveillance, as an avenue for perpetrating coercive majoritarian control, is also a frequently deployed tool. In 2022, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, a Hindutva outfit, demanded the installation of high-resolution cameras in and near every mosque, madrasa, and Muslim-majority areas “for monitoring of [sic] the activities in these places.” From surveillance aimed at public spaces—utilising overpolicing and increased deployment of surveillance apparatus like CCTV cameras—to surveillance aimed at the private sphere—through legislative measures and policies such as the Uniform Civil Code—minorities in India are already over-surveilled. These forms of intrusive state surveillance geared to the public sphere, which disproportionately impacts minorities, will only be made more frequent due to the logistical feasibility segregated living spaces afford.

Other forms of majoritarian coercion and violence, such as the economic marginalisation Muslims increasingly face can also be exacerbated by spatial segregation. Segregation can facilitate the economic marginalisation of Muslims by identifying Muslim-owned businesses and marking them with a scarlet letter by virtue of their placement in ‘Muslim areas.’ This is especially a cause for concern given the Hindutva clamour for the economic boycott of Muslims and such economic discrimination finding institutional sanction.

Increasingly, BJP-governed states like Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand have mandated that eateries visibly display the names of owners and employees, in what is clearly a bid to identify whether they are Muslim-owned. Recently, fruit vendors in Delhi’s Najafgarh were ordered to display their names and numbers on their carts by the local BJP councillor, though he claims this is aimed at preventing ‘illegal,’ Bangladeshi and Rohingya Muslims from selling produce.

The economic boycott of Muslims which is already taking shape, will only be accelerated due to ghettoisation. Wacquant believes that economic exploitation is a central aspect of ghettoisation, and this applies to ghettos in India as well. But in the specific context of Muslim ghettos in the country, beyond being sites of economic exploitation, the existence of these ghettos will also facilitate Hindutva’s economic violence against Muslims.

The existence of ‘Hindu areas‘ and ‘Muslim areas‘ not only lends itself to effectuating economic boycotts, but it also creates barriers to accessing public spaces. Spatial segregation won’t remain limited to housing but will also give rise to demarcated public spaces. Segregating public spaces into ‘Hindu‘ and ‘Muslim‘, depending on whether they are located inside or outside ghettos, will lead to the illegitimisation of Muslim people’s claim to public spaces outside ghettos and highly segregated neighbourhoods.

In 2021, Hindutva groups disrupted Friday prayers offered by Muslims in public land which was specifically marked for this use in Gurugram. This is but one of many examples of not only the barriers Muslims face in accessing public spaces but also the lens of illegitimacy their use of these spaces is viewed with. Access to and navigating public spaces are fraught with questions of social identity, desirability, respectability, power, and many other bargains; and upper-caste Hindus, due to their socio-economic and political privilege, set the parameters of access.

Further, the Hindutva narrative that Muslims are a threat to the safety of Hindus will only legitimise such segregation of public spaces. In both, the Moradabad and the Vadodara incidents, concerns regarding safety were raised. In Vadodara, the residents said the Muslim woman’s presence would lead to ‘threat and nuisance.’ In Moradabad, women’s safety was called into question if the Muslim couple were to live there. While this is merely eyewash to make Islamophobia and a desire for segregation more palatable, the myth of compromised Hindu safety is still weaponised effectively and believed widely. This aligns with Wacquant’s claim that stigma is a key feature of ghettoisation. And such stigma will spill into matters of accessing public spaces.

A fixture of Hindutva propaganda regarding threats to safety is the alarmism surrounding the safety of Hindu women. Muslim men are said to pose a threat to Hindu women, and conspiracies such as love-jihad and land-jihad are all premised on this. Ghettoisation and consequent segregation in public spaces will result in Muslim men being viewed as having legitimate access to only public spaces located in ‘Muslim areas‘ and illegitimising their access to spaces that Hindu women occupy to ‘protect‘ them.

On the flip side, the prospect of Islamophobia, combined with patriarchal control and paternalism, will substantially reduce Muslim women’s access to public spaces outside their ghettos. In Ahmedabad’s Juhapura, women say they have limited interaction with the world outside the ghetto and few public spaces they can access within it.

Shifting the blame for ghettoisation

Even though Muslims in India are driven to live in ghettos due to various socio-economic, political, and security factors, the far-right shifts the blame for ghettoisation onto them, implying Muslims choose to stay in ghettos and impose self-segregation on themselves. The choice to live in ghettos can arguably be self-imposed in certain cases, but claiming that segregation itself is self-imposed and desired ignores the reality that the drivers behind even wilful segregation are often still external. Ghettoisation is a response to an oppressive majoritarian culture and a reaction to the threats it presents.

The Sachar Committee Report, published in 2006, said of ghettoisation, “Fearing for their security, Muslims are increasingly resorting to living in ghettos across the country. This is more pronounced in communally sensitive towns and cities.”

The idea of voluntary ghettoisation should be placed within the context of the socio-economic and political climate that prevails in India and the rampant antagonism towards Muslims. And while members of ghettos may find a sense of security in living among their own, the very concept of ghettos is associated with majoritarian control. It’s the spatial manifestation of majoritarian violence. In his 2004 paper, Wacquant argued, “The ghetto is not a “natural area” produced by the “history of migration” (as Louis Wirth argued) but a special form of collective violence concretised in urban space.” Simply put, Wacquant postulates that ghettos do not arise organically due to the voluntary migration of a community to a particular area but are a manifestation—and consequence—of collective violence targeted at the ghettoised community.

A Pew Research Centre survey found that a majority of Indians expressed that they respect all religious beliefs but still preferred segregated living spaces and resisted the idea of exogamous marriages. 36 percent of Hindus surveyed said they wouldn’t accept a Muslim neighbour, as opposed to 16 percent of Muslims who said they wouldn’t accept a Hindu neighbour. Explaining this paradox, the report stated that “[Indians] simultaneously express enthusiasm for religious tolerance and a consistent preference for keeping their religious communities in segregated spheres. In other words, Indians’ concept of religious tolerance does not necessarily involve the mixing of religious communities.” While India’s Hindu majority may not have to reconcile this paradox, for India’s marginalised communities, this paradoxical thinking has devastating consequences.

Ghettoisation isn’t limited to the spatial segregation of communities but also includes the fragmentation from mainstream socio-cultural, economic, and political practices to which ghettoised communities are subjected. The prevalence of ghettoisation and acceptance of majoritarian calls for segregation also begs the question of whether critical constitutional guarantees of equality and equal access for all are susceptible to majoritarian whims, and if minorities in India are only as equal as proponents of a divisive political ideology want them to be. And if that’s so, should we then call this an institutional failure or institutional complicity?

About the author(s)