In 2019, the NDA-led government in New Delhi passed the “Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act” which institutionalised gender nonconforming individuals under an empirical definition: “persons whose gender does not match with the gender assigned at birth, including trans-man or trans-woman, persons with intersex variations, genderqueer individuals, and persons having such socio-cultural identities as Kinnar, Hijra, Aravani and Jogta.” They were now an officially recognised category under the scrutiny of the state.

The Act provided a bouquet of rights in affirmative healthcare for gender minorities, including promises to amend outdated and pathologising language being used in medical curriculum. It offered a redressal mechanism to such institutional evils as “discrimination (in education, employment, healthcare etc.) based on gender identity” without challenging the postcolonial workings of the state policy itself. Indeed, the ruling dispensation’s legislation appeared to have made some marginal strides over the preceding Congress government in being queer-friendly. And seven decades post-independence, this Act seemingly ushered in a new era of respect and dignity for transgender Indians.

But a closer inquiry will reveal the need to challenge this “categorical thinking“: a “medicalised model of legal recognition” where transgender people were mandated to seek a certificate authorising their gender identity from the District Magistrate, making compact the notion of a ‘deviant‘ population seeking ‘permission‘ to exist in a controlled manner from the State. The Act essentially failed to compensate for the transphobia rooted deep into Western imported knowledge traditions of demographic control. For one, it made these populations quantifiable and manageable by the State while redacting the dynamicity of their lived existence and the historical trajectories that have come to shape the socio-cultural fabric within which they are purled.

Moreover, the subcontinent already possessed a long tradition of gender fluidity well before European categoricalism and labels alighted upon its shore. Therefore, any developments in favour of queer-friendly policy need to be contextualised against this historical backdrop of acceptance and dignity. The colonial persists in the post-colonial existence and decolonisation is an inward-looking enquiry that challenges the tenacious superstructures of imperial rule internalised by us. A move toward decolonisation would then require scrutiny of and liberation from the very foundations of Indian transphobia in the postcolonial period.

Therefore, assuming that decolonisation is an active and ongoing ‘process,’ do we assess India’s pro-trans policies to be decolonial? This analysis is linked to the larger problem of decolonising sexuality in South Asia and will enquire into the historical trajectory of how indigenous sexual mores and knowledge traditions were “vulgarised” and marginalised by the British.

History and philosophy

Prior to the advent of colonial rule, a vast array of “world-senses“ regarding gender and sexuality proliferated in South Asia. Vedic literature elucidated thus upon the idea of biological sex: there existed three ‘natures‘ or prakritis, the pums prakriti, the stree prakriti, and the tritiya prakriti or the non-procreative ‘third-sex.’ The last of these was a “ritually auspicious and protected community.”

Other texts mentioned ‘stree dharma‘ or ‘purush dharma‘ i.e., the conduct or ‘performance‘ required of a ‘man‘ or a ‘woman‘ in social settings. Even Sanskrit, the dominant language of the day, accounted for the existence of those who did not ascribe to these binaries in the form of a wholescale third-gender called the napunsak linga. To South Asians, since times immemorial, intersexuality had not been a categorical aberration but a standalone world of experiences in itself. Texts in the Jain tradition forwarded a psychosocial approach where a person’s gender at the physical level could be different from their gender at the level of the psyche.

By contrast, the beginnings of the Renaissance period in 15th century C.E. Europe were marked by the emergence of the “man of reason” or the “thinker,” best exemplified in Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing of the ‘Vitruvian Man.’ This was a male figure of ‘perfect‘ bodily proportions that soon became the cornerstone of all Western thought, and any departure from his form was derided as ‘degeneration.’ In this manner, the emergent epistemologies of Renaissance science essentialised the white male figurehead as the epitome of all human development.

Convinced thus of their superior genes, the Europeans felt sanctioned to commence the voyages of discovery, colonising land, then cultures, and finally bodies and psyches that were regarded as inferior to their own, echoing the “genealogy of the idea of degeneration in Western thought.” As Da Vinci had mapped out the human body in his drawing, so the colonialists ventured forth to map out and categorise the uncharted terrains of the East.

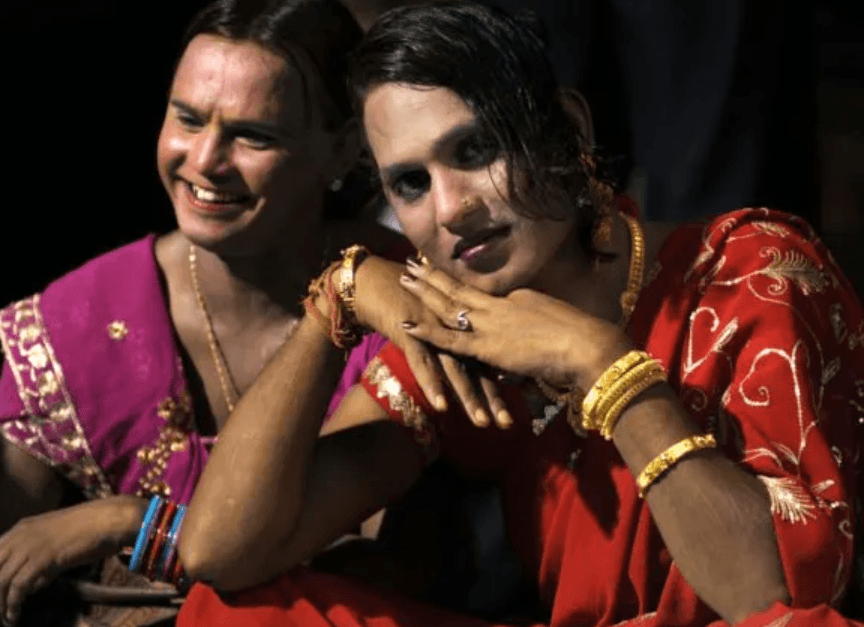

South Asia, at the dawn of colonial rule, possessed a rich tradition of gender fluidity with many different groups such as Hijras, Zananas, Sakhis, and Khwajasarais that variously dressed in feminine clothes, visited newborns to bless them as a part of “badhai” ceremonies, mentions Hinchey, performed as crossdressers in religious performances, held important political positions, or served as travelling dancers and singers. They preserved the “knowledge of (their) performance, mythology, and gendered behaviors” for posterity through chains of discipleship called “guru-chela paramparas.” The gender performance they embodied, the fluid households they organised themselves into, and the unconventional conjugal relations they formed made them altogether “illegible” to colonial sensibilities, writes Jessica Hinchey.

Western thought was obsessed with the body. Yet the idea of bodily existence was deeply repulsive to it. It sought transcendence to the level of the mind and valued above all the mechanism of thought, which was regarded solely as the domain of the perfect white man; anything ‘degenerative‘ or ‘different‘ to him was said to lead an “embodied” existence. All that concerned the body was “articulated as the debased side of human nature.” But the more it sought to escape from the body, the more it thought about the body, and the more it became about the body.

A cornerstone of Western thought was the binary understanding of bodies as ‘manly‘ or ‘womanly.’ All the dynamicity of sexuality in the subcontinent was reduced to these naturalised categories that ill-fit a sociocultural context where senses of time, space, world, gender, history, etc. were fluid. The “body politic” in South Asia was overpowered by the dominant forces of imperial history.

Colonial politics of the body

Categorisation: The British perceived their empire as one body premised on normative ideals of citizenry like ‘normal,’ procreative cis-heterosexual family units, and any threat to this body politic was dealt with with utmost seriousness. The first of these “disruptions in the imagined cohesion of the social body,” that the colonial state targeted was sexual deviance. To the colonialists, sexual ‘disorder‘ was the harbinger of political chaos, and the ever-vigilant state wanted control over the sexuality of its citizens. The colony was a queer and amorphous space upon which the coloniser now sought to impose the straight and empirical metrics of a heteromasculine regime.

The collective body of South Asian citizenry was subjugated through “census, maps, and museums” that enumerated and documented every inch of its corporeality, located the exact cause of ‘dysfunction,’ and then exterminated it through institutional mechanisms of control. One such instrumentality was the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, which “imported homophobia into Indian society” writes Hinchey, by codifying intersexuality into lawbooks as nefarious behaviour and creating a hitherto nonexistent ‘homosexual‘ identity.

The colonial gaze that fell upon the newly colonised bodies failed to identify third-genderism as a whole set of lived and embodied experiences. The intersex bodies didn’t fit the ideal proportions of a colonial heteromasculine body that was either manly or womanly and followed a “procreative sexuality,” writes Hinchey. As a body of citizenry, their domestic arrangements, conjugal partnerships, and “guru-chela” lineages of inheritance didn’t fit into the colonial state’s rigid “sexual regimes” marked by “heterosexual conjugality and patrilineal succession.” Finally, their cultural practices, which made them mobile performers, also didn’t fit into colonial borders, making it difficult for the authorities to keep track of and document them.

Intersex existence was reimagined by the British in horrific terms as a filthy, diseased, and contagious ailment of the body politic that required immediate diagnosis and corrective measures. Thus, the CTA was deployed to enumerate and quantify intersex bodies by clubbing all their diversity under the umbrella terminology of ‘hijra/eunuch.’ Categorised thus, they became a population under the control and mercy of a foreign power that little understood the subcontinent’s traditions except as cold and empirical data points. And most importantly, the CTA of 1871 also mandated them to be ‘registered,’ with the district police, which is starkly mirrored by the TPA of 2019.

These attempts at writing a script of deviance and institutional control onto a body that otherwise refuses to be legible under the ideals of a cis-heteronormative state are therefore not a new function of the Indian government, but in fact a 150-year-old colonial import.

Vulgarisation: In his 1965 text ‘Rabelais and His World,’ the Russian author Mikhail Bakhtin elucidated upon ‘Carnival‘: a festivity that is dissolutive of all social mores and order in favour of stricken chaos. It defiles all highbrow and refined social norms, expunges class boundaries, and allows a temporary social liberation that defies the otherwise stuffy comport of ruling classes. The Carnival exposes the imaginary social hierarchies for what they are and commits sacrilege against all that is considered sacrosanct and empyrean. It is a time for the “lowering of all that is abstract, spiritual, noble, and ideal to the material level” of the body, for bodily functions to be spoken of in brazen terms, and for the “grotesque realism” of the earthy and tangible human condition to be expressed in public.

South Asia also possesses centuries-old traditions of the “carnivalesque” where gender fluidity is performed with gusto in open defiance of the social order of the day. For instance, the Chamayavilakku in Kerala, where men dress to the nines to pay obeisance to goddess Durga; the Launda Naach, a folk theatre in UP; and the Koovagam in Tamil Nadu, which is India’s largest annual congregation of transgender women as a part of celebrations of the Aravani sect. At these festivals, people make great revelry by cross-dressing to dance and sing and have intercourse in public spaces as a part of ritual practices.

It was this Carnival that became the focal point of intersex resistance against colonial rule. In fact, even before the arrival of the British, the everyday peculiarities of intersex people itself were carnivalesque: they frequently donned female attire, sang and danced in public, made erotic jokes in common parlance, or shamed class injunctions by baring their castrated bodies. With the onset of British hegemony, any display of sexuality in a ‘degenerate.’ East was automatically “vulgarised” and deprivileged as debased, plebeian, and embodied. The Carnival therefore acquired a more conscious social form in opposition to the crackdown from the colonial authorities, inadvertently becoming a mode of resistance in the very act of intersex existence.

Unsurprisingly, the TPA of 2019 mirrors the CTA of 1871 in the state’s intention of keeping its hegemony over power and narratives intact through language that marginalises and “vulgarises.” The post-colonial politics of the body is steeped so deeply in colonial-era mores that it is difficult to characterise the current pro-trans policies of the state as decolonial.

In order to truly decolonise such and more policy trajectories, India must turn inwards in a process that Walter Mignolo called “border gnosis” (2000): privileging the modes of knowledge that emerge outside of Western, hegemonic epistemologies.

Decolonisation is an active and perpetual ‘process’ that can be brought to fruition only by indigenising policy discourse to privilege the lived experiences of the marginalised for whom said legislations are being drafted, and by looking back to our pre-colonial history for answers on who we, the South Asian body politic, actually are.