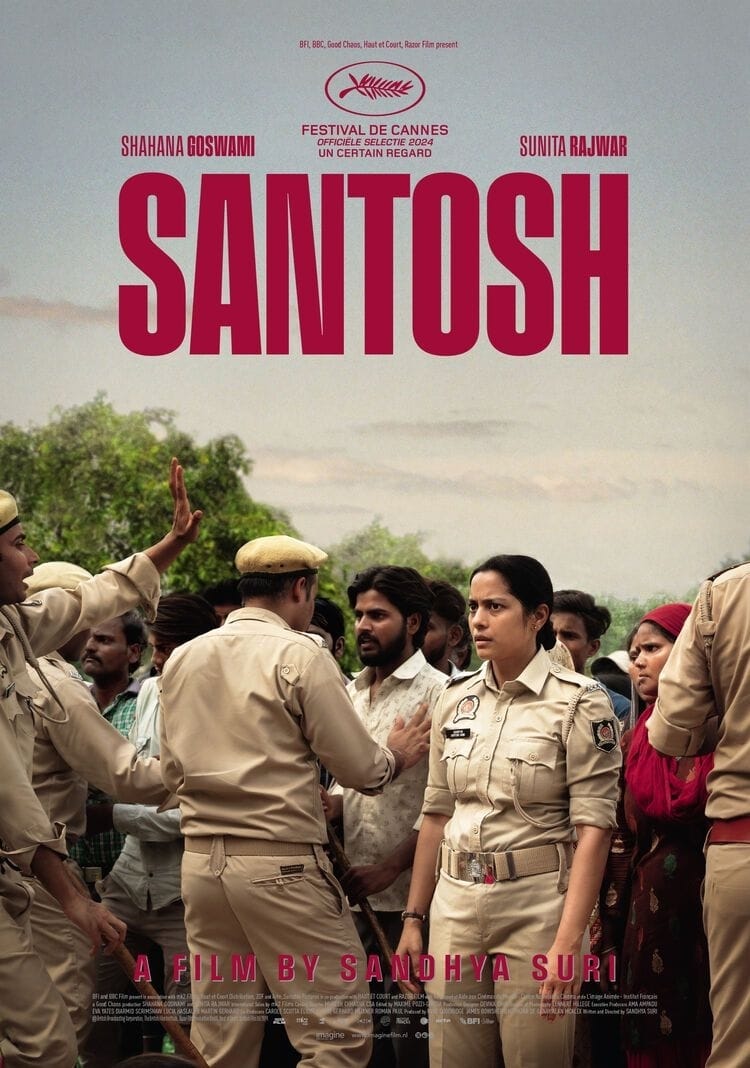

The story of Santosh Saini (Shahana Goswami) happens in a fictional world, Sandhya Suri calls it Chirag Pradesh. She is the widowed wife of Raman, who died in a communal clash in Neerut, another fictional invention of Suri that closely resonates with the real location, Uttar Pradesh’s Meerut. She inherits the constable job upon the death of her husband under Ashrit quota (compassionate recruitment).

She is the widowed wife of Raman, who died in a communal clash in Neerut, another fictional invention of Suri that closely resonates with the real location, Uttar Pradesh’s Meerut.

She quietly accepts the job as the life in Chirag Pradesh doesn’t offer much to a woman except taunts and humiliation, especially if she is a widowed woman who had married for love against the will of her in-laws, perhaps her family too.

Pseudonymous India

The cardinal necessity of journalism, sometimes– depending on the story–, is to use the asterisk (the symbol *), when the writers are using pseudonyms for the names of either victims or for the source; to conceal the identities. Santosh is very closely inspired by the real events that happen in India, so much so that it almost feels like a visual adaptation of a personal essay of a reporter who had also happened to be a constable at one point. Along with the use of pseudonyms and the non-judgemental representation of the truth of India, an added layer of skepticism makes Santosh even more realistic, mirroring the realities in India.

Santosh finds a Dalit father urging a cobbler– who is also an unofficial man to write statements on behalf of complainants. She believes that she can help him in some way as she is now a part of the system. The high-ranking police officers humiliate him, while chit chatting with the upper caste big-men (pradhan, the president) of the village.

No one in the police station cares to listen to a man whose young daughter has gone missing. The police officer doesn’t even give the serious attention that a case of a missing girl needs, but amuses himself and the others around him for the Dalit man had a toilet in his home, mocking the public’s ‘whining‘ of ‘politicians not doing enough for them‘. A few days later, Deepika Pipal is found inside a well, dead and raped.

Santosh doesn’t need to use any such asterisks to tell the story of current India that registers on average a rape for every 15 minutes. Uttar Pradesh ranks highest in the country for registering the most number of complaints with the National Commission for Women. So, the pseudonymous paralleling of India’s reality in Santosh is evident and direct.

However, the choice of using the pseudonyms is not to be seen as a not-so-brave creative choice because, the makers might have decided to do so to escape the censorship and criticism of maligning the “image” of India on the global stage.

However, the choice of using the pseudonyms is not to be seen as a not-so-brave creative choice because, the makers might have decided to do so to escape the censorship and criticism of maligning the “image” of India on the global stage. Whatever the reasons are for adding pseudonyms, the purpose of mirroring the real events of India is served in the most undramatic, non-judgemental and realistic manner.

The non-judgemental gaze in Santosh

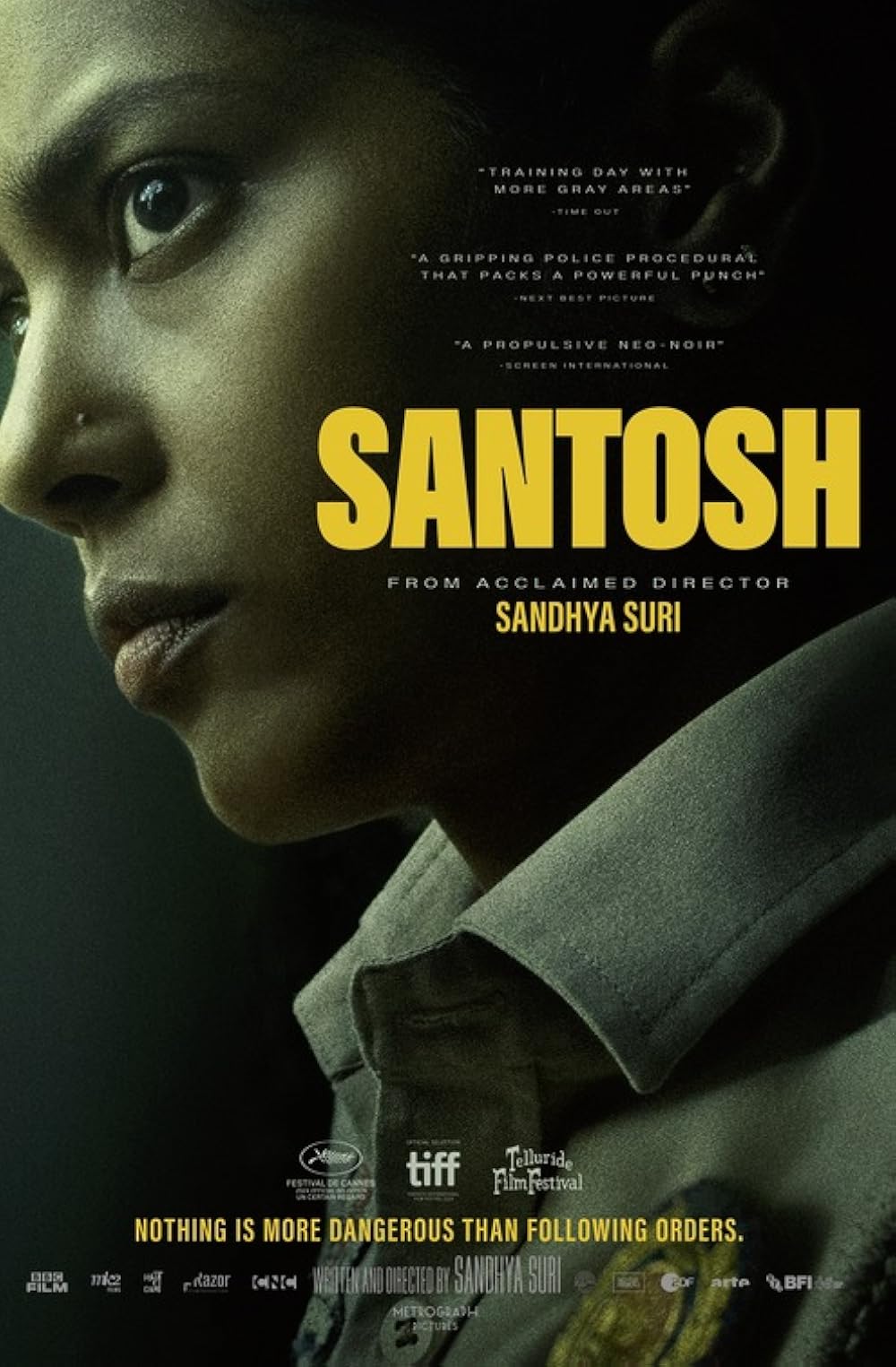

Santosh Saini was not trained to be a police officer. She had to choose between being an unemployed widow in a sexist world and being a police constable in the same sexist world– but only with a khaki uniform and a decent pay. That might have been Santosh’s first day at the police station. She is listening to the case form a college girl filing a complaint against her male classmate who supposedly had promised the young lady to marry her, but now refuses to do so after being physically intimate.

As Santosh goes to bring the key of the women’s toilet that was locked for unexplained and unexplainable reasons– the common theme across India, even evidenced by Shilpa Phadke in her seminal work Why Loiter…, is seen, with the college girl slapping the boy left and right in front of the male police officers in a secluded parts of the station.

We also see the non-aggrieved father of the girl, giving bribe to the police through the underaged chaiwala. Why was the bribe given? For delivering “justice”? Or, was the girl “framing” the boy? Was he really the culprit as the girl claims? Shouldn’t there be the benefit of doubt before taking the claims of women as matter of fact? We don’t know. Santosh watches all these events as baffled as you might be.

Yet, the film conveniently escapes the judgement of the characters, showing nothing but the everyday events of India, including everyday sexism, everyday bribery and everyday disappearances and rapes of women.

Yet, the film conveniently escapes the judgement of the characters, showing nothing but the everyday events of India, including everyday sexism, everyday bribery and everyday disappearances and rapes of women.

Knowing when to quit

After Thakur has been transferred due to his negligent behaviour (He performs the shuddhi pooja, purification ritual, of the police station because a raped and dead dalit girl was brought to his police station.), Geeta Sharma (Sunita Rajwar) comes as the officer-in-charge to solve the crime. Sharma is a long player in this game. She knows the tactics and tricks of the trade.

For a very brief moment, we experience the gentle sisterhood that we recently saw in Payal Kapadia’a All We Imagine As Light. However, that slowly fades away as Santosh’s consciousness hits her harder after her near-death whipping of Saleem, the now-dead innocent accused in the rape case of Deepika Pipal. The extra judicial custodial torture is also a quite common feature in India, including the custodial deaths.

The death of Saleem doesn’t have any empathetic impact on Sharma as it does on Santosh Saini. Maybe that’s what it does to you once you are in for a long game. Perhaps that’s why, before becoming thick-skinned, Santosh may have realised to quit the long game, quit everything and leave everything behind– including giving away her nose jewellery– that was gifted to her by Sharma– to an underaged girl who sells biscuits at the railway station and also returning Deepika’s ear-rings back to her family– that were taken from her dead body at the mortuary ward.

Santosh is a realistic police procedural drama that relies more on revealing the real events of India than to solve the crime as a traditional crime-thriller to punish the real perpetrator. Because, that doesn’t quite happen in India, does it?

About the author(s)

Azdhan (He/Him) is a full-time film critic freelancing for Feminism In India. If he is not reading or writing, he will just be zoning-out– even if there is no window– always thinking of writing his next novel to adapt it into a screenplay. The backend process of trying to build something that can solve urban loneliness is also always on his mind.