Squid Game Season 2 premiered on Netflix on December 26, 2024. The sequel to the most-watched series on the platform met with a lukewarm reception. The mixed reviews added to the muddle of chaos. Season 2 is unlike the first season; it is a nuanced continuation of the story of survival.

The second season metaphorically portrays the ups and downs of life. While the first season emphasises the basic human needs of hunger, greed, and survival, the second season matures to realising human emotions. The contestants are now real people with families and stories beyond their mistakes.

The capitalism of it all

Squid Game 2 begins with a commentary on capitalism, where a suited man bears the ‘white man’s burden‘ to judge people as trash. He identifies homeless poor people and plays with their greed and needs to make them choose between bread and lottery tickets. A subtle commentary on human relations and human greed is smart writing and direction by Hwang Dong-hyuk.

The Halloween party from which Seong Gi-hun is taken to the game venue showcases how big Squid Game 1 has become. A party with all masked men and women clad in glitter and diamonds depicts Gi-hun as a winner trying to return out of curiosity and not a starving father trying to earn for his daughter and lost dignity.

The dystopian thriller comes too close to reality when Gi-hun’s long-time friend Lee Seo-hwan, as Jung Bae, enters the game. The man who refused to lend Gi-hun money, which ultimately led to his mother’s death, is now a co-contestant in the game of life, death, and money. In a crucial moment towards the end, he even apologises for his refusal to help a friend. The relationship is rekindled under extreme circumstances, ultimately commenting on the nature of money in capitalism and how it impacts human relationships.

Human relationships entangled in games

Squid Game 1 was easier for its audience to grasp. It was thrilling, with almost no human guilt. The contestants of the game had met on set, and their lives were left outside the island. Their deaths were gruesome, but the realisation that they had mothers or that their deaths would leave orphans behind was amiss.

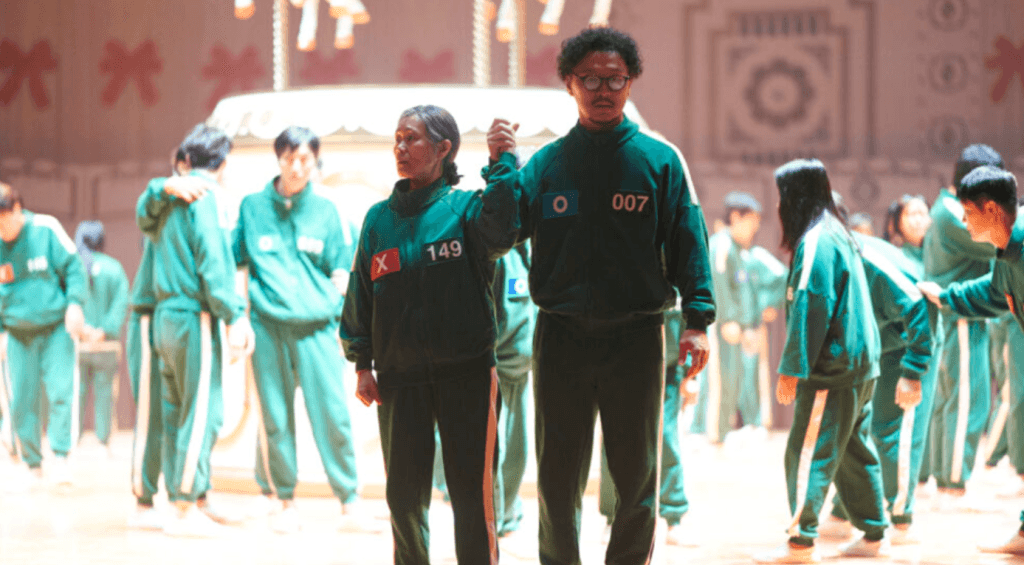

The second season showcases a couple, a pregnant woman, a mother-son, a couple of friends, and a shaman. It is a group of human relationships that we live with every day, and any death leaves the audience guilty of accomplice. Perhaps the bad reviews were also derived from the realisation that they are not some game bots but real people.

The dystopia shatters…or does it?

Squid Game is a dystopian thriller series. It imagines a capitalist totalitarian state (on an island) in which there is grave injustice or suffering. At the oust, the games are democratic with an easy exit. A democratic vote takes place at the end of every game, and the side that wins is obliged.

On the face of it, it is a democratic practice, but on the inside, it is a rotten system. Much like every voting practice, free will is a myth. It is manipulated by force and greed. The pressure is not just external; colleagues also create an insane amount of pressure to choose a side. In the sequel, the players wear their vote on their chest, quite literally. The sides are divided, and in-fighting becomes gruesome. The catalyst in this edition of the games is not just hunger but politics.

Not enough deaths in Squid Game 2

One common critique about this season is that there are not enough deaths in this edition of Squid Game. A hero, Gi-hun, takes it upon himself to save people and stop the game. Ironically, caught in the game, he averts many deaths and schemes ways to guide participants on how to play games so the chance of living increases.

There are deaths, but the shock has vanished. Unlike the first season and the first game, where nobody expected people to die in a child’s game, the audience’s expectations soared high during this season. The deaths were not as many; the players knew when to run and when to stop. A review in the Inverse states that “the biggest problem with the series” was that there simply weren’t “enough deaths.”

It was probably designed to explain why the future games changed; all subsequent rounds differed from the first edition of Squid Game. The games, not as many as the first season, were enough to keep the audience glued. The detailed depiction rounds in the Mingle were both hilarious and heartbreaking.

The hero complex

Squid Game season 2 carefully dissects the phenomenon of the hero complex. The stubborn saviour who returns to the game of death to rescue others and shut the dystopian pleasure factory is all too filmy. The masculine need to create a hero is just pitiable. The writer has created Gi-hun’s character through the need to create a chaotic world and then save it.

Gi-hun, or player 456, tries to meet the Front Man and stop the game, but when he fails, he enters it as a contestant. He spends his fortune to re-enter the game only to create chaos and result in many more deaths. The hero complex is undeniable between games when he re-enters the first game to save a man or when he saves a mother in the second game.

His heroism shines through and convinces people to participate, save, and rebel. The last plot is the ultimate rebellion which is orchestrated by stealing ammunition from the soldiers and making way to the quarters of the management.

He is all helping, forgiving, and oblivious that his friend, player 001, is but a Front Man, as hinted at many moments through the series. The hero is on a mission and the villain is a friend. The series has ended on a cliffhanger moment where the identities have been revealed, but the realisation and consequent struggle will ensue.

At the crux of it, Squid Game is the story of a hero trying to save his people and burn down the bad island that has caused too much suffering.

The writer-director Hwang Dong-hyuuk’s efforts to create a Korean series with Korean games and innuendos for the world are remarkable. The simplicity through which each game has been explained and portrayed must be appreciated.

A lot of nuances are also lost in translation. A scene where the son asks his mother to imagine the stone to be his father’s mistress’ face is actually an ill translation. The word closest to the Korean word is hair, which refers to the Korean cultural mention of women pulling each other’s hair, a common sight in Korean dramas.

The ironic hopeful background music in the game Mingle and the use of background score in every other game is an intentional assertion. They get lost when communicating with the world outside as the culture can only so much be communicated through a foreign language.

The second season is engrossing and rewarding; it leaves the audience anticipating the third season that is scheduled to air later this year. Despite the mixed reviews, it still remains the most-watched series on Netflix. This season requires patience and attention, and after a slow hour and a half of building up the story, the season catches up with the pace and takes its audience through the roller coaster of emotions.

About the author(s)

Dr. Guni Vats is an Assistant Professor at the Department of English, Manav Rachna International Institute of Research and Studies. A PhD in Gender Studies, she is a renowned researcher, writer, and scholar.