Before the patriarchs claimed the altars and pulpits, women still had some land to stand on—as priestesses, prophets, and divine symbols. The door that was resoundingly shut on their collective face seems to be ajar—but does it count? As the Vatican takes an unprecedented step, let’s look closer at women in organised religion—historically on the sidelines?

Earlier this month, the Vatican City made headlines for appointing Sister Simona Brambilla as the Prefect of the Dicastery for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life—a first-of-its-kind appointment and the highest seat ever occupied by a woman in a major Vatican office. Is this a cause for celebration? Is this a milestone moment in the unending tunnel of women’s empowerment? Is it too little to be called progress in the 21st century? Or are we just nitpicking and should celebrate the throwaway victories?

Religion: a pillar of patriarchy

Feminism has rarely seen eye to eye with organised religion, except maybe to confront them. Few things hold as much power in our world as religion does, and it has been shaping society’s moral and ethical framework. It has also proved to be one of the most powerful tools to not only reinforce patriarchy but create its standards—a tool historically used to limit women’s rights, freedom, and autonomy.

In 2018, the former president of Ireland called the Catholic Church “an empire of misogyny,”- citing the lack of women in leadership roles in the church, anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ stances, resistance to women being ordained as priests, and constant censorship. Pope Francis was the first to express support for increased inclusion of women in Vatican jobs, and only after he overhauled the governance of the Roman Curia was it possible for people not ordained to hold high office. The same pope adhered to the Catholic Church’s hardline against women being ordained as priests, citing the Marian principle:- “The way is not only [ordained] ministry. The Church is a woman. The Church is a spouse. We have not developed a theology of women that reflects this.” We shall let that information seep in as we look at women in other organised religions around the world and how they have fared thus far.

Women’s evolving leadership across religions

The Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism claims that women had no place in Buddha’s first monastic order. His foster mother and stepmother, Mahapajapati Gotami, marched to Vaishali with 500 female followers to persuade him otherwise. The four sanghas established by Buddha thereafter recognise the male monks as “bhikkhus” and the female as “bhikkhunis.”

South Asian history has had many women saints—especially from the Bhakti tradition and after, like Meera, Andal, or Akka Mahadevi—who have rejected marriage and domestic life to dedicate their lives in search of spiritual answers. But they have historically remained on the margins. Today, Buddhism is practiced widely and makes up the majority population in countries like Thailand, Burma, or Cambodia. These three countries, coming from Theravada traditions, also share another trait—they do not officially recognise Bhikkhunis. For over 1,000 years, Sri Lanka had no Bhikkunis, as their lineage was wiped out due to persecution by southern Indian kings. In 1998, nuns were ordained for the first time in a millennium, sparking both growth to over 4,000 Bhikkunis and controversy, with some traditionalists opposing their re-establishment. While the 21st century grapples with Buddhism’s gender apartheid, in 2021 a new Buddhist monastery was excavated—claimed to have been led by Buddhist nun Vijayashree Bhadra with the support of Queen Mallika Devi—in the 11th or 12th century.

In 245 BCE, Arahanta Bhikkhuni Sanghamitta (“Friend of the Sangha’), the daughter of Emperor Asoka, was travelling the world to propagate Buddha’s teachings and principles of the sangha. Yet in 2001, the headline read that Dhammananda had become Thailand’s first fully ordained (albeit still not recognised) Bhikkhuni, trailblazing the way for more unofficial Buddhist nuns in the country. It is still illegal in many countries to be ordained.

In 2021, victorious news came in that women have been finally allowed to sing in the Golden Temple. This came after the Punjab Assembly unanimously passed a resolution urging the Akal Takht and the SGPC to allow Sikh women to sing hymns in the sanctum sanctorum. Sikh women have been very active but overshadowed figures in the religious activities. In the 15th and 16th centuries, Bebe Nanaki was the first Sikh and supporter of Guru Nanak’s mission; Mata Sulakhni played a supportive role during Guru Nanak’s travels; and Mata Khivi was a proponent of langar sewa. In the 17th century, Bibi Amro influenced Guru Amar Das and became a leader of a manji (administrative unit), while Mata Nanaki supported and raised Guru Gobind Singh, and Kaula aka Mata Kaulan became a disciple of Guru Hargobind. In the 18th century, Mai Bhago was a warrior who led Sikh forces against the Mughal army; Deep Kaur was a fighter known for her self-defence and valour; and Bibi Mumtaz was known for serving injured Sikh warriors during the Battle of Anandpur Sahib. The silent but steady part of caregivers has been played by Sikh women, but they have never been allowed centre stage. Years later, political parties and religious groups are arguing if women should be allowed to sing in one of the holiest temples of the religion. Sounds about right.

The Jewish holy body, Talmud, recognises 48 prophets and seven prophetesses of the Jewish people. Sarah, the matriarch of monotheism; Miriam, a leader during the Exodus; Deborah, a judge and prophetess; Chanah, who revolutionised Jewish prayer traditions; Abigail, known for her wisdom and prophecy; Huldah, a prophetess during King Josiah’s reign; and Esther, a queen and saviour, each played crucial roles in the religion, albeit outnumbered by the male counterparts but relevant in their prophetic messaging. In 1890, Rachel “Ray” Frank became the first Jewish woman to preach formally from a pulpit in the United States—nicknamed later “the Girl Rabbi of the Golden West.”

A 2023 documentary threw light on what facilitated that: “Ray Frank had this opportunity in the Wild West … because things were not as established because roots were not laid down because things were still starting up. And out of necessity, she was the one who could do it,” Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin of Temple Sinai says in the film. It was as late as 1972 when rabbinical schools began ordaining women.

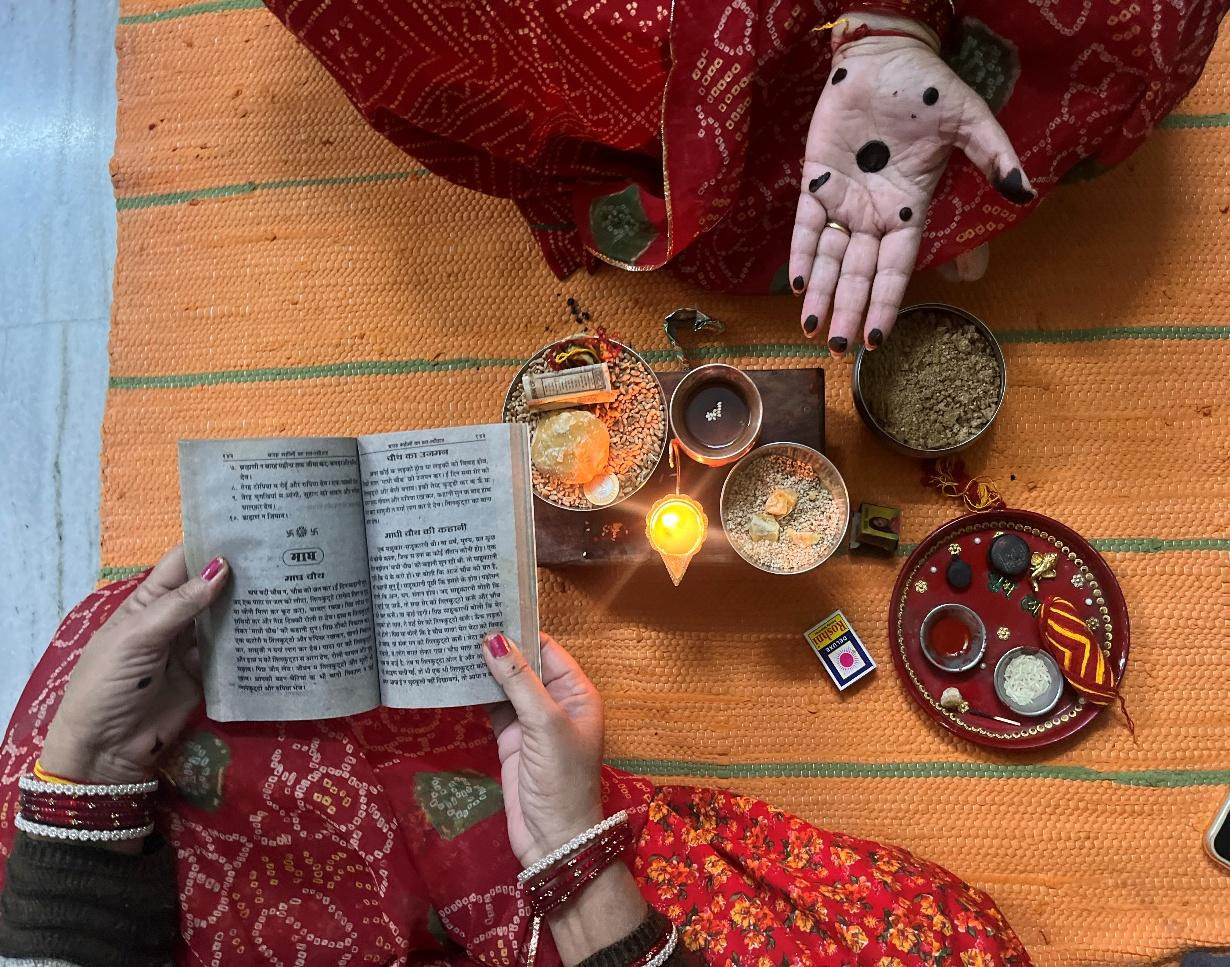

Gargi, Maitreyi, and Lopamudra are the three most distinguished names from the Early Vedic Age. They were philosophers, scholars, public speakers, and advisors, and Maitreyi-Gargi is often credited with contributing to composing the Upanishads (overwhelmingly written by men). Gargi was also the advisor to King Janaka. She famously silenced a renowned sage by posing an unanswerable question, which can be simplified into: “Where is the realm of the Gods located?” Under the banner of the same religion, the 21st century saw women making history by entering one of the holiest temples—Samarimala—for the first time ever. The same religion that worships a menstruating goddess (Ambubachi) did not allow menstruating mortals to cross its holy threshold.

In 2010, women priests were beginning to make headlines as some institutions, namely in Pune, started recognising them. In 2014, Sandhyavandanam Lakshmi Devi became the first woman to conduct rituals in Andhra Pradesh. In 2018, Nandini Bhowmik made the loudest noise as the first of her kind from Bengal to conduct the holiest of rituals—the wedding ceremony. They went ahead and Tagore-ised the Vedic rituals and did away with Kanyadan and its likes—one wonders though, how deeply has patriarchy been shaken since then?

Legacy of struggle: Icons of women’s power and resistance

Prophet Muhammad’s first wife, Khadija bint al-Khuwaylid, also known as “Mother of Believers,” is an inspiring and powerful icon from Islamic history. Known to have been wealthy in her own right, she is credited with funding and supporting the Prophet and Islam in its early days. Sumayya Bint Khayyat, a Black Abyssinian woman who had been freed from slavery, was among the first women to accept Islam and is considered to be the first martyr in Islam in 615 AD. In 859 AD, Fatima bint Muhammad Al-Fihriyya (as credited) founded the al-Qarawiyyin mosque in Morocco alongside the University of al-Qarawiyyin, the first degree-granting educational institute in the world. Years passed, and the more conservative and masculine voice thrived in the religion, pushing women away from the limelight and deeming them unfit to lead.

In 2015, Algerian women imams made headlines for fighting at the forefront of Algeria’s battle against Islamic radicalisation, dedicated to steering women away from false preachers promoting radical forms of Islam. In 2016, Sherin Khankan founded a mosque in central Copenhagen, challenging Islamophobia. In 2018, Jamitha, the general secretary of Quran Sunn, made headlines as the first woman to lead Friday prayers in Kerala. In 2022, Egypt’s Al-Azhar appointed its first female adviser to the Grand Imam, Dr. Nahla Al-Saeedy. Women imams, the few around the world, are actively challenging the male-dominated religion while combating global Islamophobia. And that makes the fight even more complex.

Women like Phoebe, a deacon mentioned by Paul in Romans 16:1, played active roles in the early Christian communities in the first century, preaching, teaching, and leading prayers. Many, many (and many) years later, Ellen G. White, an American author, co-founded the Seventh-day Adventist Church with her husband in 1863. She was a key figure in the protestant group of early Adventists. Sarah Melissa Granger Kimball was the early leader of the Relief Society of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 19th century. It was also during this time that the suffrage movement was swelling and the Catholic Church was its most consistent opponent. Women have globally earned the right to vote in democracies, but the Catholic Church is seeing neo-suffrages, advocating for women’s voting rights in church synods and equal leadership roles. And getting arrested for it. Closer home, a 2019 report by AP’s investigation revealed decades of sexual abuse of nuns by priests in India.

A 2016 report observed that in 61 of the 192 countries, women were at least 2 percentage points more likely than men to have an affiliation; in the remaining, both genders levelled at more or less the same mark. There were no countries in which men were more religiously affiliated than women by 2 percentage points or more. Will we find absolution through the holy and hallowed halls of religion that have historically tried to shut the doors on them, or is the answer in dismantling the entire building? To invoke the Lorde, “… the master’s tool will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”

A few weeks before this appointment, a piece of quieter news passed us by that the Vatican is considering classifying ‘spiritual abuse’ as a new Catholic crime. The new law was being pushed to address cases “where priests use purported mystical experiences as a pretext for harming others.” It is up to us what we consider to be harmful. It is great news that a woman has been appointed to the most celebrated church’s high office. But that is it. That is the news.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo

The Prathyaksha Raksha Daiva Sabha (PRDS) a religious movement, founded by Poikayil Appachan in 1910, was a transformative movement in Kerala that fought caste discrimination and promoted spiritual and social liberation. PRDS’ approach to gender equality was revolutionary for its time, giving women significant roles in all aspects of life, including as priests and leaders who led congregations and guided the faithful. V Janamma, Known as Poyikayil Ammachi led the religious movement for more than 40 years, making her one of the only women in the world to lead a religious movement for such a large period