Simone De Beauvoir observed a century earlier that womanhood is not being but becoming. With the passage of time, this process of ‘becoming‘ has mutated in several ways, so as to keep up with contemporaneity. It is a rigorous one, which begins right from the time a daughter is born, catching up to shackle their little feet long before they learn to walk. Sisters and brothers neither play with the same toys nor dress in like colours. Such conditioning from childhood fosters a blindness towards this lifelong process of ‘production of girlhood,’ which tightens its grip as a little girl continues to age.

Adolescence becomes a crucial preparatory period for this little girl’s final and sure emergence into the structures erected by the patriarchy.‘Teen Girls‘ are a particularly impressionable demographic category, bombarded by media that influences their behaviour and actions to make them more palatable in an increasingly patriarchal society.

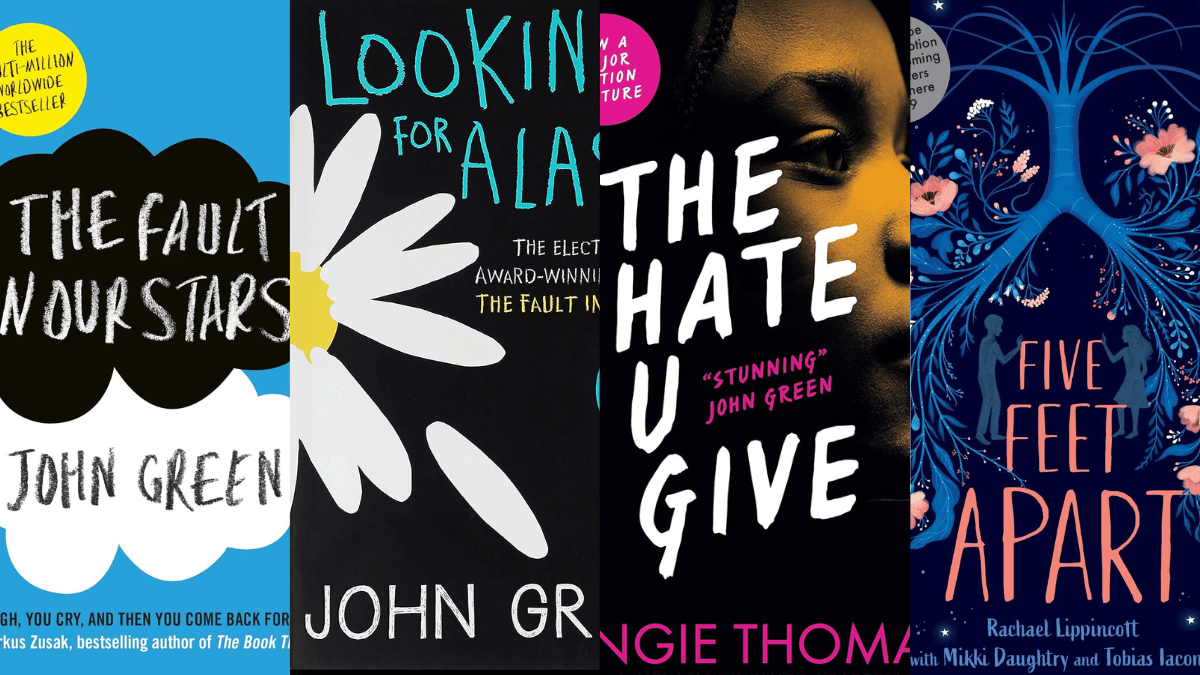

Young Adult novels are crucial examples of this phenomenon. The genre of Young Adult literature, widely read by teens everywhere for its lucidity and relatability, vividly affects the ways in which its readers engage with the world around them. Primarily consisting of male writers, the (male) protagonists in these books (such as those written by John Green) are accompanied in their coming-of-age process by memorable and exceptional female characters, constructed according to the stereotype of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl. These were exceptionally talented, memorable, and vivacious young women. They seized everything life had to offer them. Every moment spent with them was a riot, every conversation an enlightenment.

The plague of the manic pixie dream girl

The infamous and notorious titular protagonist of Looking for Alaska has been widely known and perceived through this stereotype. The film critic Nathan Rabin coined the term, also named and concretised by a man, to refer to female characters in narratives that revolve around a male protagonist, whose life is given meaning under their tutelage.

Thus, Alaska Young could have bloomed into a memorable woman, claiming the pen and the voice to tell her own story whenever she wished to tell it, to whoever she wished to tell it. With her persistent love for literature, her charming sarcasm, and her mischievous ideas, she managed to steal into the title of the novel, only to be caught up in a world created by a man, only for another man.

A similar fate is bestowed upon Margo Roth Spiegelman in Paper Towns. Throughout the novel, the only facet of her existence that the reader is familiar with is that which strikes Quentin, the male protagonist: her mysteriousness. The extensive and perpetual process of construing Margo as a mystery can be pinned down to minimal efforts on the part of the male protagonist to know her; yet, what one gets out of this ‘fashioning of the girl as a cipher,’ is the message that women are enigmatic, unknown, and unknowable creatures. This inconspicuous, yet insiduous process catalyses the cultural production of girlhood so as to instill in young girls the belief that their life needs to be devoted to a man’s cause so that the world may remember them favourably.

Despite the garb of rebellion and transgression the Manic Pixie Dream Girl is clothed in, she ultimately remains a testosterone-fuelled, pubertal male fantasy. What Green fails (or rather, refuses) to give his readers is what these girls do with their own lives. Every sparkling figment of their potential fizzled out once the male protagonists had had their epiphanic moment, which would enable them to grow up into bigshots who could preach and preen other men into geniuses, not unlike Dr. Hyde in Looking for Alaska. When Margo left off her readers with a Quentin who had finally grown into his years, she seemed to be limiting herself to the margins of the black notebook she had previously authored. It takes years to realise that the author of this young woman had always been a man—be it Quentin, through whose narration the reader came to know Margo, or Green himself, through whose writing Margo was brought into her fictitious being.

When Alaska dies, so as to prove how utterly fallacious it is to attempt to know a person inside and out, one feels her death to be an abyss. Yet, in the plot, her demise is a mere narrative device to propel Miles headfirst into his ‘Great Perhaps.’ Are these really the girls a teenager must wish to emulate? Or, probing the concern further, are these the only models Young Adult Fiction can provide to its readers? Was it absolutely empty of girls who could be looked up to for themselves and what they contributed to their fictional communities and to the community of readers banking upon them?

No country for young girls?

Such pressing questions demanded a thorough examination of a genre that has encouraged several young people to pick up books with wonder, as opposed to the usual boredom and disdain that school curricula entailed. Surprisingly, this critical journey does not leave one in utter despair. It also strengthens the conviction that people you can look up to are always around the corner. What needs to be done, even today, is to urge these figures to the forefront for young women to recall as vividly as a Margo or an Alaska.

Moxie, by Jennifer Mathieu, provides the reader with such a heroine, who evolves from a victim of patriarchal objectification into an agent of liberation from such misogynistic processes. The book also highlights the importance of unconventional literature in bringing about political movements, as Vivian Carter (the protagonist) creates a zine to foster solidarity among the girls at her school, catalysing them into action against the misogynistic institutional framework of their high school. She has her mother to look up to, whose tireless activism and rebellion in her own school day are presented as legends, which awes both the reader and Vivian. One thus also infers the pressing need for galvanising figures girls can look up to so as to foster awareness of their own agency and push them to exercise it, renouncing passivity.

Angie Thomas’ critically acclaimed work, The Hate U Give, also provides the reader with such a figure. The novel has achieved widespread recognition, being longlisted for the National Book Award for Young Adult Literature and even receiving honours such as the William C. Morris Award and Amelia Elizabeth Walden Award, among others. With a headstrong protagonist who is not defined by a ‘romance,’ yet who grows through the realistic, diverse, and multifaceted relationships she creates and sustains, Thomas vociferates the need for diversity and politicisation in the Young Adult canon. Its readers may be kids with raging hormones, but they are also humans with maturing hearts. For every ‘kid who is angry at the world‘ whom adults disdain, there exists a thinking, feeling, and raging soul against this crumbling world order.

Starr Carter, Thomas’ protagonist, stands as a pioneer, a woman of colour who feistily fights against her own marginalisation and that of her community. After a shocking act of violence against her friend, she refuses to sit quiet and let the adults do the talking, in startling acts of defiance against her concerned parents, who ultimately do join forces to support her. This instance highlights the importance of parental and familial support in the lives of young women (as does Moxie), who can go out as capable and determined individuals into the world only if they have been raised to shout rather than to succumb.

Rethinking gender, one page at a time

In India, where every girl—even adult women with economic independence and social maturity—is hushed by her family in the face of a patriarchal society, literature needs to construct a path for them to tread. The books one reads have to help foster the realisation of one’s own myriad potentialities, as opposed to the glorification of martyrdom in the name of men. Why must your brother have access to a better education than you? Is your husband’s job more important? Why must your father’s word be the law and yours mere angry rebellion? These are the questions that should arise from the books teenage girls in India, and throughout the globe, read. To increase the awareness and accessibility of such books should be focused on, as opposed to raucously lamenting the death of reading among youngsters.

Great article and a pleasure to read!

Excellent Ishani 👍❤️ your writing skill always amazes me❤️

Best wishes 😘😘😘😘

beautiful. just beautiful.