Gujarati literature has a rich cultural history, but like other literature, Gujarati literature remains male-dominated and inherently patriarchal. To understand the representation of women in Gujarati literature, it is essential to look at the ways women have been portrayed in traditional Gujarati folk literature. If we look at the folk stories of Saurashtra, we find the depiction of women as noble, heroic, and revolting against the socio-cultural norms. These folk tales portrayed women in two extreme shades—either as fierce and majestic or as victims, where she needed a man’s saviour.

Many of the women characters who were portrayed by earlier Gujarati writers were ideal Indian women who remained obedient and followed their husbands. But like other literary movements, the feminist movement and emerging gender theory had a great impact on Gujarati literature. Later writers like Pannalal Patel, R. V. Pathak, Manubhai Pancholi, Umashankar Joshi, Jhaverchand Meghani, etc., had strong women characters in their work; for example, Pannalal Patel’s Manvi ni Bhavai portrayed strong characters like Raju, but with most of this writer’s women characters, the traditional gender roles were maintained. Gandhi and some of his ideas, which remain traditional, had a significant impact on these mainstream writers. Gandhian literature remained dominant in the trends of writing until the 1960s. Also, Gandhi and his ideas impacted the women writers of pre-independence Gujarat.

Early representation of women

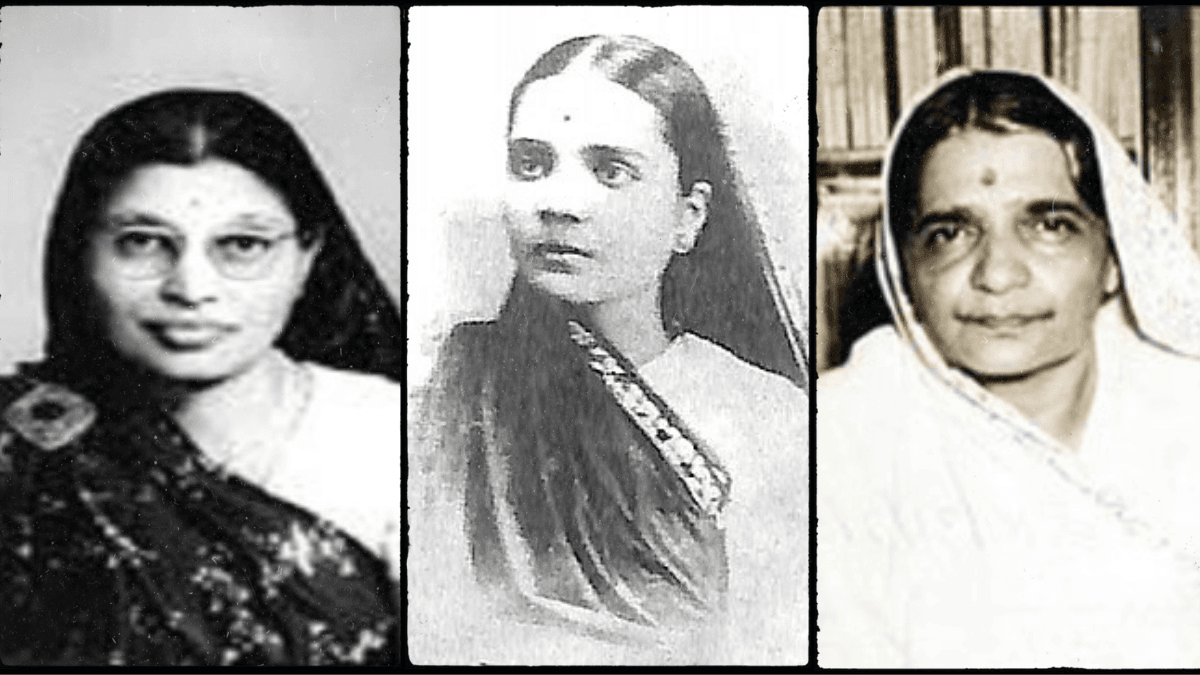

Prof. Pratixa Parikh pointed out that the Gujarati journals for women during the 19th century, like Sudha, Stree Bodh, Sundari Subodh, etc., had a significant impact on the development of feminist consciousness and brought change in society. Gujarati women’s writings were majorly pioneered by upper-caste elite women. Some prominent ones are Vidyagauri Nilkanth, Lilavati Munshi, Hansa Mehta, and others. For most of these writers, they addressed the challenges faced by women in a patriarchal society. These writers’ female characters centred around the changing lives of women who were conscious of their rights to protest against a patriarchal system, and they dared to question the patriarchal system. In the end, most of these characters also reinforced the traditional gender norms.

One of the examples is Lilavati Munshi literature. In her literature, she depicted the psychological points of view of the modern woman. Most of her fiction posits the trials of an insurgent woman full of life and romance; despite the modern outlook and individuality of her female characters, they end up as traditional Gujarati women. Vanmalani Dairy (Diary of Vanmala), by Lilavati Munshi, is also a good example of the earliest feminist consciousness in Gujarati literature. In this work, she depicted a widow and how she used her acting skills to become an independent woman. Lilavati Munshi’s legacy remained grey in feminist writings; some of her work radically attacked patriarchal norms, while most of it reinforced those norms, but her legacy inspired many other writers later on.

During the 1940s, women started participating in the freedom movement, and it also had a great impact on men’s writings. The rise of feminist thought in India also had a significant impact on the flow of women’s writings in Gujarati literature.

1950s to the 1980s, the beginning of change in women’s writings

This period witnessed radical change in women’s writings, and the representations of women became more important, and the depiction of women from a feminist lens became a basic tool for many writers. Dhiruben Patel, Kundanika Kapadia, Saroj Pathak, Varsha Adalja, Ila Mehta, Himanshi Shelat, Panna Naik, Chandra Shrimali, etc., used a rebellious tone, and some radical transformation in the psyche of the women characters was observed who were not ready to compromise and were fully aware of their rights and equal status.

Such a change started with writers like Dhiruben Patel; in her novel Shimlana Fool (Flowers from Shimlana), the protagonist Ranna’s husband used to physically abuse her, but she ended up leaving him and his house in search of her true identity. This trend continued, and such examples are also seen in Kundanika Kapadia’s Sat pagla aakash ma (Seven Steps to Sky). Kapadia portrayed the main character, Vasudha, as rebellious, and she left home. Here Kapadia also emphasised the impact of toxic masculinity on men. Kundinika Kapadia’s work, Sat Pagla aakash ma, is considered the finest novel crafted from a feminist lens. The novel starts with the statement: “All are unequal in the world, but women are more.”

Tarini Desai’s Mahalakshmi deals with age-old oppressive Indian systems where widows are considered inauspicious; the main character in the story resists norms when she participates in her sons’ marriage rituals. Another short story by Kundanika Kapadia, Nyay (Justice) shows the women’s exploitation in marriage and how the main character walked out of marriage.

Varsha Adalja’s novels, including Mare Pan Ek Ghar Hoi (I Wish I Also Had One Home) and Sag Ne Sankoro, offer nuanced portrayals of middle-class, educated women navigating the tensions between tradition and modernity, self and society. Saroj Pathak’s Sarika Pinjarastha (Sarika, the Encaged) is a story where she also points out how societal norms are oppressive over women.

Contemporary representation and rise of intersectionality

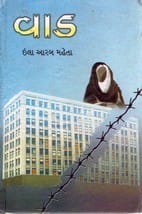

During the 1980s, the third feminist wave in the West came up with ideas like intersectionality, where the marginality of one happened because of their various identities. The idea of intersectionality also impacted Gujarati women’s writings. Writers like Chandra Shrimali addressed the exploitation of Dalit women. In her works, Himanshi Shelat also explores the plight of widows in rural India. One can notice this intersectionality in Ila Arab Mehta’s vaad (Dialogue) also, where she portrayed the struggle of a Muslim woman called Fatima Lokhandwala and her exploitation because of her several identities. Through Fatima, Ila Arab Mehta shows the changing image of women in modern times who do not think in terms of religion, status, or society and dare to face any given situation to lead an independent life.

Writers like Bindu Bhatt in her work Mira Yagnikni Diary (Diary of Mira Yagnik) explore the lesbian relationship between Vrunda and Mira. It was contemporary to Deepa Mehta’s Fire, which also talks about this taboo at that time. In her work, Bindu Bhatt portrayed Mira as a strong woman never ashamed of her bisexual identity; she also dealt with leprosy, where her lover, Vrunda, left her, but she continues to break the patriarchal norms by living alone. Writers like Suvarna also explore lesbian relationships in her seminal work, Tou Tou Kevu Saru (How Nice It Would Be).

In her famous work, Chaka Chakini Adhunki Bodhkatha (A Modern Fable of Two Sparrows), writer Swati Mehd used a popular animal-bird story to tell what freedom looks like; her story was about a she-sparrow and her freedom. Women writers in many cases use mythological stories, and they retell those stories. Ila Arab Mehta’s Batris putlini vedana (Pain of Thirty-two Dolls), which she retells from a feminist lens, is based on mediaeval Gujarati poet Shamal’s poem Sinhasan Battisi (32 Fairries on Thrones). In the preface of the novel, Mehta writes, “Neither Goddess nor demons, allow us to be women.”

Feminist thought had an impact on male characters as well; earlier, men were portrayed as traditional masculine men who began exploiting women. Now in women’s writings, they became more sensitive and emotional; Vinod is one example from Kundanika Kapadia’s Sat pagla aakash ma (Seven Steps to Sky).

Gujarati women’s writings and literature overall witnessed tremendous change in a few decades in the style of writing, the matter, and the theme. More and more women-centric works break down the dominant traditional literature. Gujarati women’s writings gave few brilliant, radical works where one can see the depiction of the subaltern. Sociologist Promilla Kapur analyses the change: “With a change in women’s personal status and social status has come a change in her way of thinking and feelings, and the past half century has witnessed great changes in attitudes towards sex, love, and marriage.“

References:

- http://www.researchdirections.org/abstractread.php?id=429

- https://old.rhimrj.co.in/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/RHIMRJ20150210004.pdf

- https://www.britannica.com/art/Gujarati-literature

- https://amp.scroll.in/article/1076598/meet-the-gujarati-women-writers-who-wrote-innovative-fiction-memoirs-and-poetry

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/handle/10603/316674

About the author(s)

Faga Jaypal is a final year history student at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, with a keen interest in intellectual history, gender and sexuality studies, social justice, and cultural studies. Passionate about literature, books, and museums, he combines his love for storytelling with academic research. Aspiring to become a teacher like Mr. Keating, he seeks to explore history through diverse narratives.

Well researched article, I am glad to came across this article and got to know about lot of things about Gujarati women’s literature.