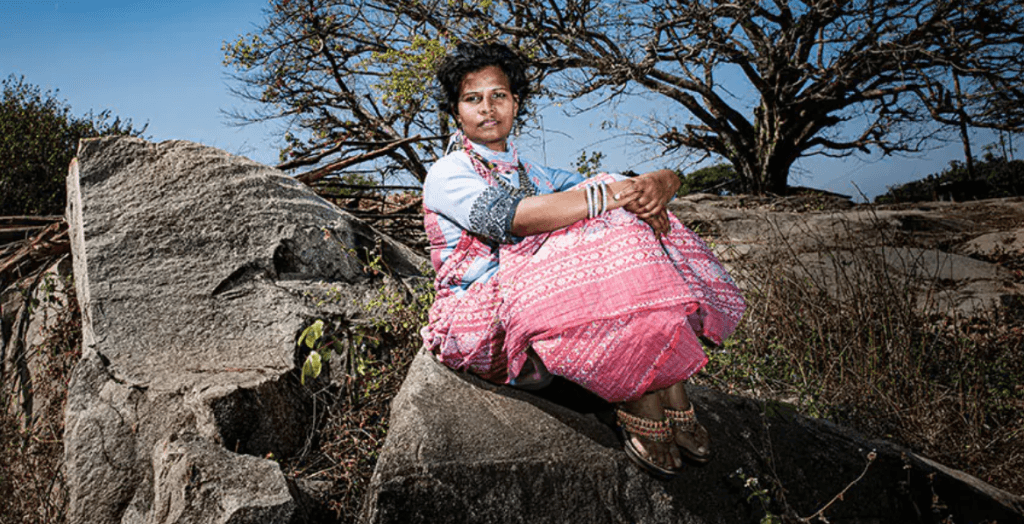

While writing about Jacinta Kerketta, one should be aware of how challenging and difficult it is for a woman of Kerketta’s social position to have reached where she has. Her social position refers to her intersectional identity, marginalised due to her ethnicity and gender as well as the region she belongs to. A writer who has induced hope in her fellow Jharkhandis, a hope that her poetry can save Jharkhand’s forest and its landscape. Her writing adds an insider woman’s perspective to the literature available on the Indian Adivasis. Defending her choice of Hindi as her writing language instead of her mother tongue, she explains how it is necessary for her writings to reach the audience that is responsible for what the Adivasis have had to suffer.

In Ishwar and Bazar, she elaborates her understanding of what being an Adivasi means:

“Closeness to the earth is being Adivasi

Closeness to nature is being Adivasi

Flowing like a river

Being simple is being Adivasi

Rebellion against all relations in and out,

Is being Adivasi.“

Jacinta Kerketta’s poetry

The renowned poet William Wordsworth has famously written about his style of writing poems, which he describes as a “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” When Jacinta Kerketta describes her style of writing poetry in an interview to Ashley Tellis, one can see a glimpse of the Wordsworthian method in it: she informs how “most of the poems have been written in one go…If poems are not written in one flow, they are never written again.” She explains that poetry for her comes with a power in her body and leaves behind just silence. She wrote her first poem while she was still in school for “Rahee,” a magazine for children, which would reach different states of the country, and she received many letters about how her poetry would impact other kids. The theme of the poem, like many of her initial works, was based on her mother. She grew up to become a journalist by profession, to be able to write about the Adivasi from her perspective of an insider.

However, she eventually found poetry as a better mode of expression than journalism and started travelling and writing. Her first book, Angor, was published in 2016, in both Hindi and English, by Rubi Hembrom’s publishing house Adivaani. In Angor, her poems oscillate between the themes of motherhood, poverty, environmental destruction, Adivasi struggles and others. Later, the Hindi/German version Glut came out, published by Draupadi Verlaag. Her second collection, titled Jadon ki Zameen, was published by Bharatiya Jnanpith in 2018. Ishwar aur Bazar is her latest poetry collection, published in 2022 by Rajkamal Publications. The themes of Ishwar aur Bazar range from religion and politics to Adivasi identity and struggles.

Poetry and/or activism

Kerketta is also referred to as an activist and is frequently questioned on how she separates her identity as a poet from that of an activist; she is further questioned about the separateness of her politics and poetry. Questions like these fail to recognise how the art of writing itself is a political act and is not necessarily devoid of it. Prose and poetry, through writing or orally, have always constituted movements, either on a large scale or through everyday life. Kerketta writes social media posts about the struggles of different kinds of people; even her prose can be recognised as possessing a rhythmic quality to it.

The question arises, at what point does her prose end and poetry start, and where do they intersect? Does it become activist writing if written in prose, and if it is a poem, does it lose its right to still be activist writing? The attempt to separate literary writing from the daily reality of the world and limit it to mere fragments of imagination is complicated and doesn’t recognise the power of literary works. Kerketta herself claims that the act of her writing as an Adivasi woman is a political act in itself. Her inspiration to write, she expresses to Tellis, is the “life of the Adivasis struggling on the land, the Adivasi worldview, the wisdom of the common people, their poetry-like speech… Grassroots people who live poetry.” Her poetry embodies the local narratives of these grassroots people that contribute to the grand narratives of the anthropocene, or deterritorialisation.

In Angor, she writes about the deforestation of the Saranda forest in Jharkhand and the people involved in it:

“Hands stained with the blood

Of a thousand slaughtered trees

Quietly wash themselves clean

In the rivers of Saranda“

A calm rage

An interviewer, Nidhi Kundalia, writes about how one would expect her to be “incandescent with rage. But her calm tone as she chooses her words carefully shows that she is beyond rage, having achieved some sort of transcendence instead.” Kerketta talks about the discrimination she faced as an Adivasi girl in school; though initially, it filled her with rage, she worked on her inner transformation towards “reducing envy, rage, inner reaction, and laziness” and concentrated on her studies. These words reflect a precocious child who grew up before time through the social experiences she faced, a child with social awareness and a realisation of her social position in society. These are the experiences that echo in her writings as well as her personal choices, like her refusal to accept an India Today group award because the Indian media didn’t pay attention to the Manipur incident.

Recently she was also recognised as the social science thinker of the next decade by The Print, which credited her work for India’s Adivasis “seeks to amplify marginalised voices and advocate for social justice.” Kerketta’s writing is full of rage as well as hope that these poems become a medium for raising the consciousness of the masses.

About the author(s)

Mrinalini Raj is a senior research fellow in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at IIT Roorkee, India. Her research revolves around the Indian Indigenous women and the discourse on spatiality. She has received the Charles Wallace research grant for the year 2024.