‘Failure is inevitable; it is only a matter of time.’

For many students in higher education, this sentiment encapsulates the experience of navigating India’s demanding academic landscape. Balancing non-rigid class schedules, social obligations, mentor relationships, and institutional deadlines often feel overwhelming. In a system designed to maximise output, failure can feel less like a reflection of personal skill and more like an inevitability. But what if the role of a student wasn’t designed for you? And what if that isn’t your fault?

ADHD in academia: twice the turmoil

Imagine your mental resources failing you at critical moments, leaving you paralysed in disorganisation. Projects become insurmountable, and no amount of effort can reverse the cumulative impact of previous underperformance. You find yourself stuck in a loop of damage control while watching peers seemingly thrive under the same circumstances.

For students with ADHD, particularly those undiagnosed or diagnosed late, this scenario is all too familiar.

For students with ADHD, particularly those undiagnosed or diagnosed late, this scenario is all too familiar. The ADHD experience is marked by feelings of isolation, overwhelm, and disconnection, fueled by the unstructured approach they often adopt out of necessity rather than choice. In highly competitive academic environments that demand structure and consistency, students with ADHD tend to grapple with executive dysfunction, a hallmark of ADHD, making it difficult to organise tasks, manage time, and sustain attention.

Paradoxically, ADHD also brings periods of hyperfocus: intense, prolonged concentration on tasks of interest, often at the expense of basic bodily needs like food or sleep.

‘Sometimes I get so caught up in a task that I enjoy, it becomes difficult to stop engaging with it,‘ shares A, a recent master’s graduate. ‘After a long and strenuous session of high-energy focus, I feel completely exhausted. My brain just switches off for the rest of the day.‘

The struggle to balance such extremes often results in burnout, tiredness and even frequent episodes of sickness. Standard productivity tips like ‘Go for a walk,‘ ‘Keep a diary,’ or ‘Meditate‘ barely scratch the surface. As J, a former PhD student, reflects, ‘Lack of schedules in research sometimes is also detrimental for ADHD.‘ Without appropriate accommodations, the academic system can become an unrelenting cycle of stress, underperformance, and frequent illness.

Why does ADHD pose unique challenges in academia?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) defines ADHD as ‘a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development‘. While researchers debate its primary origins— genetic, or social-developmental, the impact in academic settings remains clear: variability.

Academia demands consistency in terms of timely submissions, sustained focus, and regular engagement. Yet, for individuals with ADHD, productivity fluctuates wildly.

Academia demands consistency in terms of timely submissions, sustained focus, and regular engagement. Yet, for individuals with ADHD, productivity fluctuates wildly. Days of hyper-productivity are often followed by stretches of inertia, making it difficult to meet rigid institutional expectations. ‘In India, there is a higher emphasis on memorising information to succeed in university and competitive examination, requiring prolonged focus and repetition based studying, instead of using critical thinking or problem-solving skills‘, notes Saloni Diwakar, a researcher and academician.

Coupled with long lecture and examination hours, the education system allows for ‘limited formats teachers can use for classroom engagement‘, not creating a space for teachers to interact with students.

‘Academia evaluates you as if you’re a machine of consistent output,’ notes A, ‘But ADHD doesn’t work like that. We need flexibility—especially with deadlines and long-term projects.’

The systemic failure lies not in the students but in the institutions themselves. Insufficient policies, lack of awareness, and inadequate support mechanisms exacerbate ADHD-related challenges.

The general population underestimates the prevalence of ADHD. In reality, studies have reported an 11.32% prevalence of ADHD in primary school Indian children, with an estimated 90% of individuals diagnosed in childhood reporting experiencing symptoms throughout adulthood. A study on ADHD in North India suggests that the prevalence of Adult ADHD is around 5.48% to 25.7%. Despite insight from a few studies, the data does not provide a holistic picture of the prevalence of ADHD in specific populations and among students in academia.

Despite insight from a few studies, the data does not provide a holistic picture of the prevalence of ADHD in specific populations and among students in academia.

Referencing statistics from other countries, a study in Belgium reported that individuals with ADHD comprise 1.4% to 8.3% of first-year university students. This evidence gives a snapshot of the impact of ADHD on academic performance and points towards the need to introduce appropriate policies for neurodiverse students. Especially in India, where data on adult ADHD remains sparse and non-representative, many students fall through the cracks. This invisibility is particularly glaring at intersections of caste, class, gender, and socioeconomic status, where marginalised neurodiverse individuals face compounded disadvantages in terms of access to healthcare and experience of mental health concerns.

Improving learning environments for neurodiverse students

In the classroom setting, structures and teaching methods often clash with the needs of neurodiverse students. N, a third-year undergraduate, explains, ‘Long, un-interactive lectures make learning less enriching, especially for someone with ADHD.‘ Simple changes like shorter class durations or increased breaks could enhance learning outcomes for both ADHD and neurotypical students.

Saloni adds to this by citing Sweden’s Human Environment Interaction (HEI) framework as an example of systemic change fostering better outcomes for neurodiverse learners. But beyond classroom adjustments, Indian institutions must adopt policies tailored to the individual needs of neurodiverse students.

Policy recommendations

One critical step to actualise this would be recognising ADHD under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016. This would mandate consistent and standardised implementation of accommodations, including flexible deadlines and extended exam times across institutions. Legal recognition would also help reduce stigma by increasing exposure and improving access to necessary resources.

Research-based interventions suggest that teachers enforce strategies like paced learning, and planning and goal-setting behaviours, which boost academic performance (GPA) in students with ADHD. Introducing multi-modal learning in the classroom such as incorporating projects, presentations, and hands-on activities could foster deeper engagement. Institutions can also introduce neurodiverse representation in student organisations, providing platforms for mutual support and advocacy within the community.

However, Saloni points out, ‘The student-to-teacher ratio in India, coupled with the undervaluation of teaching roles, makes it difficult to provide individualised attention or innovative testing formats.‘

However, Saloni points out, ‘The student-to-teacher ratio in India, coupled with the undervaluation of teaching roles, makes it difficult to provide individualised attention or innovative testing formats.‘ In the Indian context, smaller class sizes and personalised feedback from teachers could significantly enhance focus and task engagement, leading to greater productivity outcomes, as described in a study.

‘It’s best if the system works in conjunction ‘with the student, for the student, not the system,’‘ adds Pradipto, a master’s student, reiterating the need for greater institutional sensitivity towards the needs of students with ADHD.

Socioemotional support: the missing link

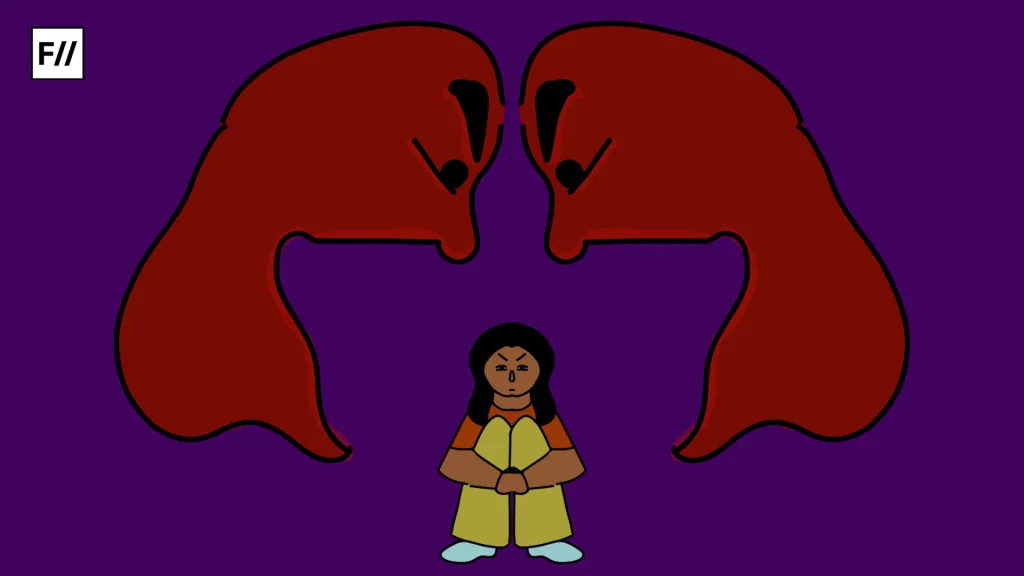

In common discourse, ADHD is thought of as an attentional problem. In reality, ADHD is better understood as a combination of difficulties presenting across spheres of life. ADHD does not just impact academics—it also hinders social integration and emotional regulation, often having a bidirectional impact on socio-academic difficulties. Emotional dysregulation, a common challenge for individuals with ADHD, often leads to frustration and diminished self-esteem.

‘It’s not just about deadlines and grades,’ A emphasises. ‘ADHD affects how you feel about yourself. Building emotional resilience is crucial.’

Institutions could address this by fostering social support networks and integrating students into peer groups or organisations

Institutions could address this by fostering social support networks and integrating students into peer groups or organisations. Such initiatives coupled with academic interventions would create a holistic framework for addressing both functional and emotional challenges in students with ADHD.

The road ahead

Addressing neurodiverse students’ needs requires systemic change at both institutional and governmental levels. By integrating research-backed strategies and lived experiences, academia can foster a more inclusive environment. Innovative approaches like game-based learning show promise in improving engagement and academic performance in individuals with ADHD.

‘At the end of the day,’ concludes P, a research intern, ‘it’s about creating a system that understands us—one that supports us to thrive rather than survive.’

About the author(s)

Avanti Karmarkar (ORCID - 0009-0007-6136-4843) is a research assistant in the Department of Psychology at Nolmë Labs with a Masters in Cognitive Science. Avanti is a curious learner and hopes to contribute to research on affective science and face perception. You can follow her on LinkedIn and Twitter.