Discrimination against Dalits and other lowered castes has continued throughout history, and resistance against this pervasive Brahminical hierarchy has also come up. From Buddha to Babasaheb Ambedkar, and later in post-colonial India, resistance has continued. The field of literature also witnessed this resistance quite prominently. Taking inspiration from Jyotiba Phule, Babasaheb’s philosophy, and the Black Panther movement in the USA, in the 1970s many Marathi writers started to write about the Dalit experience. The development of Dalit writing has later spread to Gujarati, Kannada, Punjabi, Hindi, Malayalam, and Bengali.

As William Raymond suggests about ‘dominant,’ and ‘emergent,’ culture, dominant culture is the visible practice and attitude of a particular culture, and emergent culture is the counterculture that challenges or deconstructs the dominant culture. The Dalit Panther movement in India, established by the Dalit literary movement where the leaders of that movement were the writers themselves, had a distinct identity for Dalits, and their main objective was to create a “counterculture.”

The rise of Gujarati Dalit writings

In Gujarati literature, there has been a hegemony of the Gandhian style of writing, and very little space has been given to the Dalit writing. Though Gujarat was the birthplace of Gandhi, he did not find space in the hearts of the Dalits, and it was only through Ambedkar’s influence that Dalits found their strength and voiced it out through literature. Inspired by Marathi Dalit writings, there has been a rise of Gujarati Dalit writings, which later came as a protest against violence faced by the Dalit community, especially during the anti-reservation riots of 1981 and 1985.

Dalit literature in Gujarati has successfully experimented with the regional dialects of Gujarat and has drawn extensively from the folk literature of Gujarat. The structure and style of folk songs and folk plays have been widely adopted by Dalit writers. It is a pity that little of this organic relationship between Gujarati Dalit literature and the folk literature of Gujarat can be conveyed by translations in English; an Indian language would have fared much better as a target language.

Traditional poetic forms like ‘ghazal,‘ and ‘muktak,’ have been radically remoulded by Dalit poets. Gujarati Dalit writings have had different phases; they first began in the poem and sonnet form and later took shape in many novels and plays as well. Writings of this literary movement were mainly in three styles: the first was the literary classic, and the other two were folk colloquial and dialectical. Also, scholars divided the evolution into three phases on the basis of different types.

1st phase and the emergence of Dalit kavita

The first publication of Dalit Panthers in Gujarati was started by Rameshchandra Parmar in 1975. Later there were many other magazines published; Kalo Suraj, Aakrosh, Garuda, Dalit Bandhu, and Disa were some of the more prominent ones. In the early phase, this movement was led by poets like Labhashankar Thakkar, Nirav Patel, Dalpat Chauhan, and so on. Their poetry broke through the trending Gandhian style of writing.

The first ten years after the anti-reservation movement in Gujarat marked the development of poetry, the search for self-identity, self-articulation, and the pain and anger of deprivation, oppression, exploitation, marginalisation, and humiliation were expressed in their anthology of poems called Asmita.

The second phase and rise of Dalit short stories

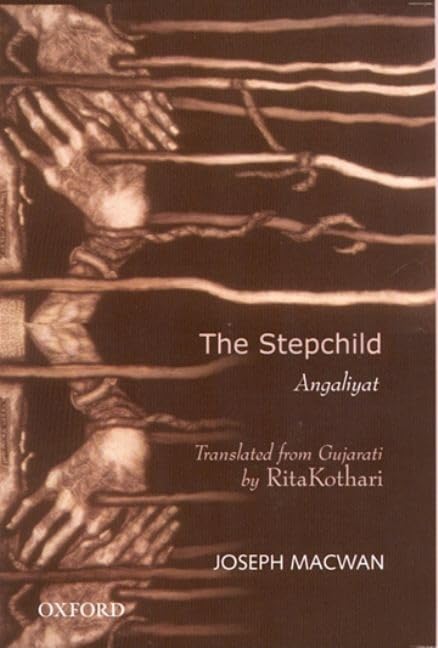

The second phase marked the arrival of short stories and novels, which came in the late 1980s. Joseph Macwan, Dalpat Chauhan, Mohan Parmar, and Harish Mangalam were some of the more prominent writers who wrote novels and short stories on the Dalit struggle. They wrote their books in rural Gujarati dialects and not in the classical elite language. Such expression led to the authenticity of the work, and it enriched the Gujarati language by re-establishing the folk tradition against the classical idiom, Prakrit against Sanskrit.

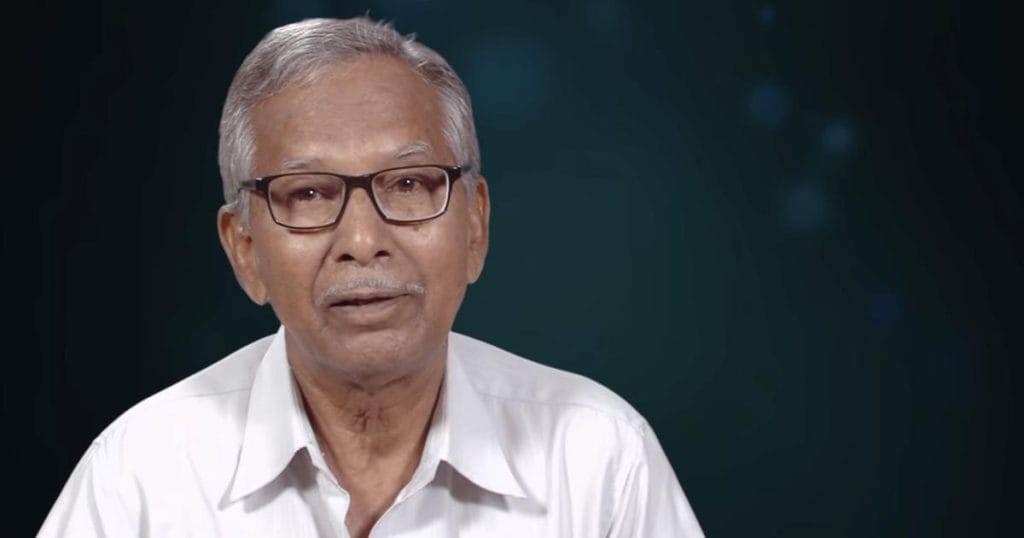

Joseph Macwan, the first Gujarati Dalit author to receive a Sahitya Akademy grant, excels as a pragmatist. Fiction and genuine overlap in his works. Macwan’s style and treatment are straightforward, however touchy and reminiscent. Macwan, the creator of “Angaliyat” (the Step Child), one of the three most acclaimed books throughout the entire existence of Gujarati literature, died in 2010. With him withdrew a period of Dalit writing, for he characterised and ruled its maxim for a long time. Quite possibly the most captivating narrators of our time, Macwan’s work was emotional, weaving stories through memory and music, breaking into elegiac tunes (Marashiya), or bringing delicate tease through wedding melodies.

Last phase and theater in Dalit writings

Gujarati Dalit literature contributed to drama as well; one of the major plays was Raju Solanki’s Bahmavadi Barakhadi, which was performed in the anti-caste reservation agitation in 1981, these riots basically against OBC and Dalit reservation. Gujarati Dalit writers write plays on the historical heroes who sacrifice their lives for the well-being of the people; their heroes are Megh Mayo, Ekalavya, Saint Rohidas, and Swami Tejananda. Dalapat Chauhan’s play Patan na Gondarethi is a very interesting play in Gujarati literature; his other works include Bhedbhava No Bhusanaro and Galafanso. Mohan Parmar is another notable Dalit playwright; his play collections are entitled Bahishkar in 2002.

The remarkable achievement of Gujarati Dalit literature is its creation of subaltern mythologies to counter the classical Hindu mythology, which was casteist and upheld Brahminical hegemony. Dalit writers came up with the stories of Eklavya, Buddha, Karna, and so on.

Harish Mangalam and Mohan Parmar both wrote many critical essays on the caste hierarchy, and in those, they discussed the struggle of Dalit people. In Gujarati Dalit literature, there are many non-Dalit authors, such as Indukumar Jani, Pravin Gadhavi, Dheeraj Brahmbhatt, and so on, who have also written about the hegemony of Brahminical culture and become vocal critics of caste hierarchy. Pravin Gadhavi, one such writer, wrote many poems and short stories through which he portrayed the struggle of Dalit lives through the non-Dalit point of view.

Dhiraj Brahmbhatt’s Tamne Pabane Joyo is a satire on the upper caste and a critique of violence against Dalits in 1981. Historically, the Dalit voice in Gujarati literature has been mostly marginalised, with only a few authors writing about it, and most of them writing about Dalits in an othering way, in a sense, which Gayatri Spivak suggests in her controversial essay about the othering of the subaltern. We find a similar sense of othering of Dalits in the writing of Gandhian and Pre-Gandhian writers as well.

The evolution of Gujarati Dalit literature is a testament to the power of narratives in shaping cultural discourse, challenging established norms, and envisioning a more equitable future. Overall, Gujarati Dalit writings came as a lack of Dalit experience in Gandhian Gujarati Writings.

About the author(s)

Faga Jaypal is a final year history student at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, with a keen interest in intellectual history, gender and sexuality studies, social justice, and cultural studies. Passionate about literature, books, and museums, he combines his love for storytelling with academic research. Aspiring to become a teacher like Mr. Keating, he seeks to explore history through diverse narratives.