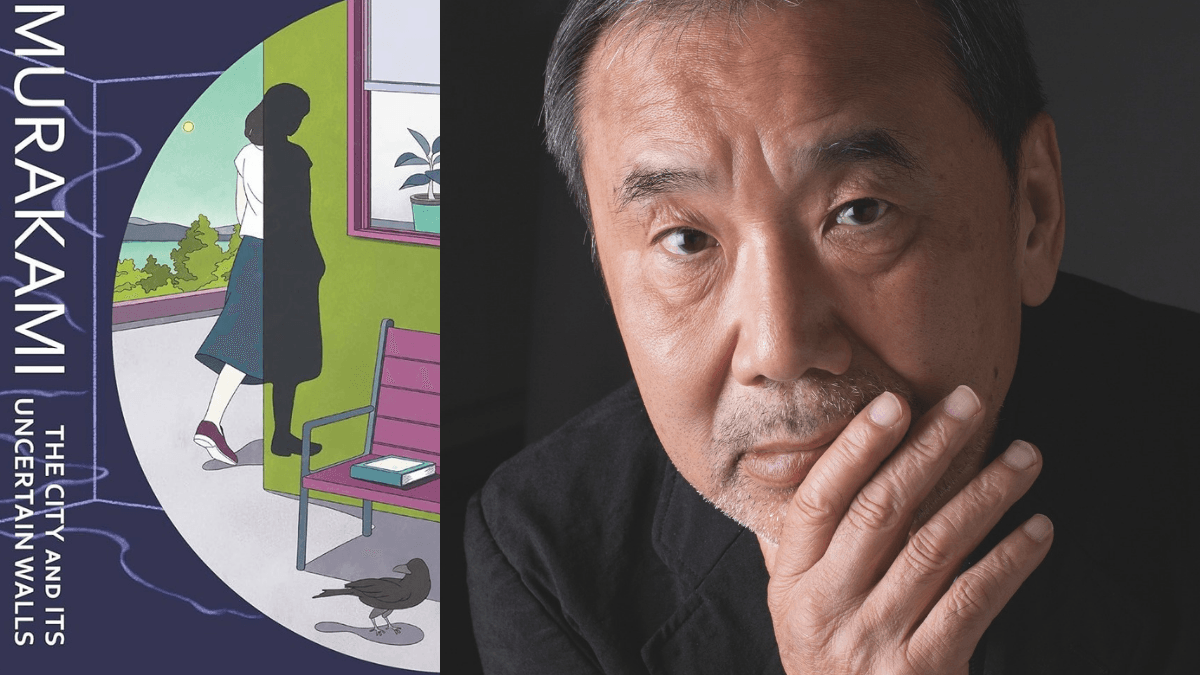

One of the unique features of Haruki Murakami’s newest novel The City and its Uncertain Walls (expertly translated by Philip Gabriel, published by Harvill Secker, London, 2024), is the afterword. More than the novel, it was the afterword where a seventy one year old writer is justifying his choice so honestly and poignantly, is enough to make readers curious especially because Murakami had hardly ever cared about criticism.

One immediately remembers Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe’s dismissal of Murakami whom he considered a champion of Western consumerism, deliberately foregoing his own rich cultural heritage in favour of Western images.

One immediately remembers Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe’s dismissal of Murakami whom he considered a champion of Western consumerism, deliberately foregoing his own rich cultural heritage in favour of Western images. Murakami’s literary career is filled with such vitriol, both from experienced and amateur critics. Murakami begins the afterword stating, ‘…but with this novel I feel I need a word of explanation‘ and proceeds to trace the literary history of the selected content; from an early novella with a similar name to the dystopian Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World.

He clarifies the necessity to rewrite similar motifs, themes, plot lines and characters, if not for anything, but the novelist’s satisfaction. He concludes by reiterating ‘Truth is not found in fixed stillness, but in ceaseless change and movement. Isn’t this the quintessential core of what stories are all about?‘ It is this forever elusive, malleable and transformative truth that Murakami seeks in this much awaited new novel. With all his characteristic humility and grace, it is the subtle plea of a more mature writer to convince his readers to give him a chance to perfect his craft.

Divided into three parts the novel follows in a typical Murakami first person narration, the male protagonist’s quest to find his beloved. Murakami mentions in the afterword how writing the novel provided him the much needed solace and safety during the Covid19 pandemic. When the world outside was ravaged by the unseen forces of an invisible fatal virus, venturing into a familiar novelistic space was one of the only ways to retain one’s sanity and faith.

When the world outside was ravaged by the unseen forces of an invisible fatal virus, venturing into a familiar novelistic space was one of the only ways to retain one’s sanity and faith.

Similarly, the two protagonists of the novel are engaged in diligently crafting an imaginary city in painstaking details, to escape the trials, tribulations, angst and pain of their monotonous existence. The city, however, is not the utopia one imagines it to be. In an interview with The New Yorker Murakami explains the metonymic dimensions of the imaginary city as the ‘worldwide pandemic lockdown‘ where he is explicating the impossibility of ‘extreme isolation and warm feelings of empathy to coexist.‘

Of reading dreams and shadows in Murakami’ The City and its Uncertain Walls

Thus, there are human beings living in impoverished minimalism, mere shells of who they could be, content with frayed dull clothes and nominal food. They have been transformed into apathetic automatons who never question their less than fortunate situations; never wonder what lies beyond this obsessive interiority. A guard passionately mans the “uncertain walls”, proudly explaining the unearthly magic in its creation.

Once someone enters the city, one’s shadow is wrenched apart, which then languishes and dies a painful death. Even the peace loving unicorns forget their bovine timidity and fight each other to brutal deaths every year without fail. Once you enter, you cannot leave by peaceful measures; and slowly your will to leave also ceases. An imaginary city then becomes a tool to critique the exclusionary practices of human beings, their wilful incarceration and their indifference to violence and death.

He further explains, ‘The image of a town surrounded by high walls may reflect that situation, of things being blocked, and obstructed‘ and intelligent readers immediately understand the contemporary relevance of similar nations and states of mind. Here the narrator is involved in reading and deciphering old dreams, evidently belonging to previous citizens, since the existing hollow ones do not possess that capacity. Dreams, often heavily sexual, have been a familiar motif in Murakami’s fiction. The self which is tormented in denial, usually finds sexual and spiritual liberation through these dreams – acting as bridges between the individual and their cherished/craved for other.

‘Believe in the existence of your other self‘

The second part where the narrator miraculously gets employed at a library in a remote mountain town is the favourite section. The intense cold, the snowy pathways, the secret room with the fireplace of apple wood, and the blurry dimensions of the spiritual and human world – all conjoin to weave typical Murakami magic. Speaking of Murakami’s magic realism, Matthew Strecher writes, ‘In virtually all of his fiction…a realistic narrative is created, then disrupted…by the bizarre or the magical.’

Strecher designates the “two worlds” of Murakami as “consciousness” and “unconsciousness”. The “unconscious” is obviously the part where the so called “magical” elements unfold, dominated by images of darkness, chill and inertia.

Strecher designates the “two worlds” of Murakami as “consciousness” and “unconsciousness”. The “unconscious” is obviously the part where the so called “magical” elements unfold, dominated by images of darkness, chill and inertia. Murakami speaks about this unconscious and names it the “black box” which is reminiscent of Brian McHale’s description of Chinese boxes as having ‘the effect of interrupting and complicating the ontological horizon of the fiction, multiplying its worlds, and laying bare the process of world-construction.‘

Murakami, however, poses a dilemma in this novel: which is the “real self” and which is its counterpart – “the unconscious”/”the shadow”? In the same interview, Murakami had quizzed, ‘Where do our real selves exist? Where does their meaning lie? What kind of place is the real world, anyway? Do we have any choices there?‘ Through all the existential dread and crises, Murakami, however, provides his characters the agency to navigate the two realms, claiming that one needs to truly “wish” to find the way out of his self.

With typical Murakamian images which readers familiar with his style would recognise in a heartbeat, the new novel is an easy read, simultaneously engrossing and exasperating. The writing has undoubtedly evolved and the scale of the narrative has broadened to incorporate multiple issues and ideas. However, one wishes for the raw, unparallel charm of his initial works. In the end, the seventy five year old master, doesn’t really need to prove his genius anymore, his oeuvre is self explanatory.