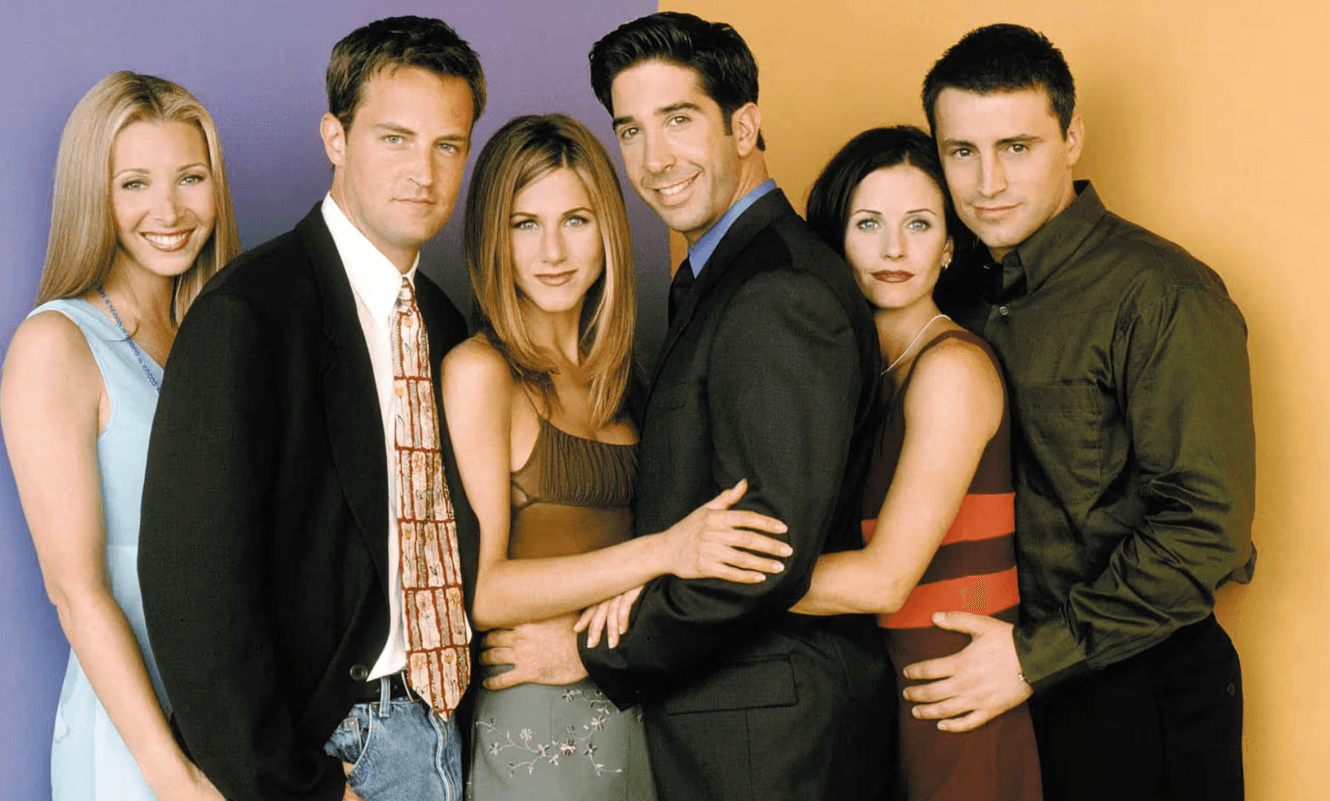

Premiered in 1994, the well-renowned American sitcom F.R.I.E.N.D.S is a cultural phenomenon, with a fan base spanning time and age. However, the enduring popularity of the show raises concerning questions about societal attitudes towards masculinity. Initially lauded for its relatable characters and humorous situations, the show has faced increasing scrutiny in recent years in its portrayal of gender roles and social dynamics.

Critics point to instances of homophobia, misogynistic humour, and outdated stereotypes surrounding masculinity, particularly evident in scenes like David Schwimmer’s Ross Geller expressing disapproval of his son playing with a Barbie doll, blaming his ex-wife’s lesbian identity for “feminising” him. The audience of the ‘90s took this scene lightly but should the audience of the 21st century do so as well?

Throughout history, society has taught men that manhood is attained through power, might, and heterosexual prowess, idealising a form of a man who typically takes the form of a hypermasculinity that is strong, aggressive and virile. Today, the dominant form of masculinity is portrayed as something antithetical to femininity, possessing qualities such as assertiveness, athleticism, confidence, and emotional restraint, all of which are frequently not associated with the feminine gender, which consequently influences men to believe that their sense of self and identity is directly derived from their capacity to dominate others. This hegemonic masculine identity encourages the domination “of the planet, of less powerful men, of women and children,” mentions hooks.

Unveiling the masculinity myth: From hegemonic ideals to deconstructing domination

During the initial years of the feminist movement, women used their anger towards the injustices meted out by their male counterparts as a catalyst for bringing about societal change for themselves (women) mentions hooks. However, as the movement gained traction, with considerable advancement in feminist thinking, feminists began to realise that men, by themselves, were not the problem.

Rather it was deeply entrenched, patriarchal notions of masculinity, which fostered sexism and male domination. That is, men are not born with an oppressive, static masculine essence; they become arbiters of the patriarchal masculine structure through repeated exhibitions of distinct, normative behaviours, which are continually constructed by the influences of a dominant culture and by the desires of individuals, mentions Butler 2011.

In the agency vs structure dichotomy, it would be wrong to accord the entire responsibility to structure for transforming boys into perpetrators of patriarchal masculinity. To say that men have no choice but to embrace the hegemonic form of masculinity that society is forcing upon them would be synonymous with saying that men have little to no agency over their lives, having little space to fight to be a different kind of man.

Similarly, putting agency at the centre of men’s actions negates the importance of structure in shaping their self and identity. In reality, the answer lies somewhere in between and this is where post-structural analyses of choice and identity serve as crucial perspectives to understand why men, more often than not, choose to conform to the oppressive, patriarchal form of masculinity that is socially accepted but morally reprehensible.

Paradox of the choosing subject: Desire, discourse, and the constraints of masculinity

According to post-structural views, individuals possess a need and a desire to act as an agent but desire is both conscious and unconscious, with the workings of discourse in unconscious desire subverting rationality. In other words, social institutions exert influence on us, creating impulses that appear to stem from inside us but are the outcome of socialisation. Such urges can undermine an individual’s so-called logical decisions or choices.

Sometimes, we can’t help ourselves from acting in ways that we know we shouldn’t or don’t want to act in, primarily because we crave benefits arising from those acts. Men are not inherently oppressive but most choose to adhere to the normative behaviours of hegemonic masculinity because such actions enable them access to particular levels of prestige, status and power in society. In this regard, we are what is known as the poststructuralist choosing subject.

For the poststructuralist choosing a subject, desire is produced through discourses in which one is both subject of and subject to. Discourses act on us, which means that they function through us, and we respond to them and alter ourselves in response to what we hear, see, and experience in society, as mentioned by Davie 1991.

We, too, are subject to such discourses, and we are inevitably confined by them. That is to say, individuals do not have the freedom to be anyone they want to be; there are boundaries that vary from person to person, based on your region and life, colour, caste, class, and gender. This is why there exists an unequal access to power between men who were able to successfully engage with hegemonic masculinity and those who cannot.

Men generally enjoy more autonomy and face fewer constraints compared to women in their expression of rationality, but their freedom is contingent upon conforming to established norms of masculinity. Deviating from these norms, such as by embracing emotions typically associated with femininity, invites denigration of one’s manhood. This societal pressure reinforces the notion that caring and emotional expression are feminine traits, limiting men’s sense of self and perpetuating the expectation of emotional stoicism.

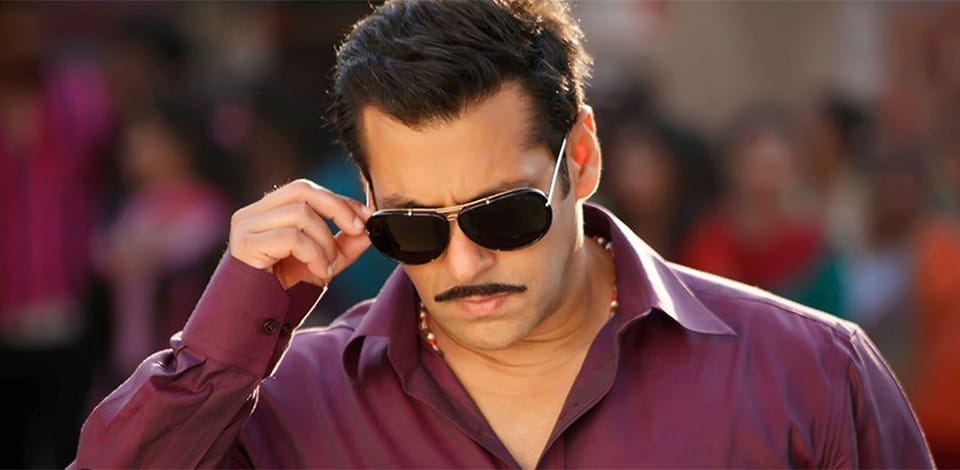

From childhood, males are often discouraged from displaying emotions, leading to a pattern of emotional suppression and reluctance to express feelings. This cultural reinforcement of stoicism is evident in phrases like “big boys don’t cry” and in popular media, exemplified by Amitabh Bachchan’s iconic line “Mard ko dard nahi hota” (“A real man feels no pain”) from the 1985 film Mard. Such attitudes contribute to difficulties for men in engaging in meaningful emotional conversations, contrasting with the perceived ease with which women communicate emotionally amongst themselves. This normalisation of traditional masculinity in popular culture perpetuates gender stereotypes and exacerbates the issue.

Evolving pop culture and people: Signs of change and the struggle for progress

From the “Angry Young Man” era of the 1960s- 1990s, constituting of macho films like Sholay, Deewar, and Don to films like Dabangg, and Kabir Singh of the 21st century, Bollywood actors have repeatedly shown that manhood is asserted and reasserted by engaging in violent duels with the bad guys and saving their love interests from dire misfortunes. When half of the theatre, mostly men, erupted into cheers and screams after Shahid Kapoor beat up a few guys, who weren’t even half as toxic as he was, under the influence of drugs and alcohol in Kabir Singh, the other half, mostly women, was genuinely baffled because nothing about that scene was right.

Neither Shahid’s chosen ways to deal with his angst and emotional turbulence caused by his girlfriend’s decision to marry another man nor his way to reaffirm his manhood to himself, and maybe even the viewers, after being dumped by a girl. This is not to say that earlier films did not include scenes of male actors shedding a few tears on screen. They most certainly did but, more often than not, these scenes were played by male actors who were portraying father roles. In such a case, the act of crying was not perceived as a taint of masculinity.

Rather, the tears reasserted the male character’s sense of authority, while he played the role of the quintessential loving father. Amrish Puri’s red-eyed, lachrymose outburst “Ja Simran Ja” in Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge is a clear example of this along with numerous jewellery ads portraying fathers marrying off their daughters in a pink-eyed ceremony.

However, it is also important to note that in recent times there has been a plethora of films, which challenged the sexist stereotypes inherent in patriarchal masculinity by showcasing men in roles that weren’t written to liberate or save their female counterparts. Instead, they were based on an equation that was supportive in nature, with the roles of the female and male actors working in tandem, on an equal footing, to take forward the storyline.

Along with being non-threatened by the limelight enjoyed by their female partners, these male roles faced no inhibitions in expressing themselves, all the while being comfortable in their skin i.e. with their masculinity. When Darsheel Safary’s character cried for his mother after moving into boarding school at a tender age in Taare Zameen Par, when Vicky Kaushal’s character expressed the same degree of nervousness as Alia Bhatt’s character in their shared bedroom after their marriage in Raazi, when Ranbir Kapoor’s character broke down more than three times in Ae Dil Hai Mushkil to give vent to his vulnerabilities, it instilled hope in me to believe that the portrayal of masculinity on silver screen is evolving and changing for the better. While the creation of such humanising male characters is truly a welcomed move, popular culture won’t be enough to dismantle the hegemonic masculine notion of men being the caricature of just two feelings: joy and happiness, with nothing in between.

Many men hesitate to shed the constraints of traditional masculinity due to the fear of homophobic labelling. Any deviation from stereotypically masculine activities, like sports, towards interests often associated with femininity, like fashion or makeup, can lead to assumptions about their sexuality, despite such interests having no bearing on orientation. This stems from a deep-rooted societal bias that assigns sexist and prejudiced stigma to men who express themselves outside rigid gender norms. Even globally successful artists like BTS face unwarranted questioning about their sexual identities simply because of their perceived “effeminate” style of dressing and use of makeup. Their overnight stardom was almost instantly accompanied by articles that dissected their fashion choices, highlighting the pervasiveness of these harmful stereotypes, even in cultures like India where such expressions remain unfamiliar.

This brings us back to post-structural analyses of identity as it is based on the idea that there is no obvious truth to identity- that what we think of as ourselves is shaped by the signals we get from society from the minute we are born. This means that we all function within a limited range of options and that individuals have varied levels of access to different discursive viewpoints. Feminist masculinity, a vision of new masculine identity as dreamt by hooks “where self‐esteem and self‐love of one’s unique being forms the basis of identity,” can only be established by dismantling the limitedness of this range of options i.e. boundaries between what constitutes masculinity and what constitutes femininity.

Towards the attainment of this goal, hooks suggest anti-sexist caregiving as the tool because care acts as discursive disciplining of how to be a man or a woman in a post-structural interpretation. As hooks writes, “a feminist vision which embraces feminist masculinity, which loves boys and men and demands on their behalf every right that we desire for girls and women” is needed to create a world wherein men are free to play with dolls, to wear costumes of the opposing gender, to paint their nails in bright colours, without being subjected to an interrogation of their sexual orientations and inclinations.

.