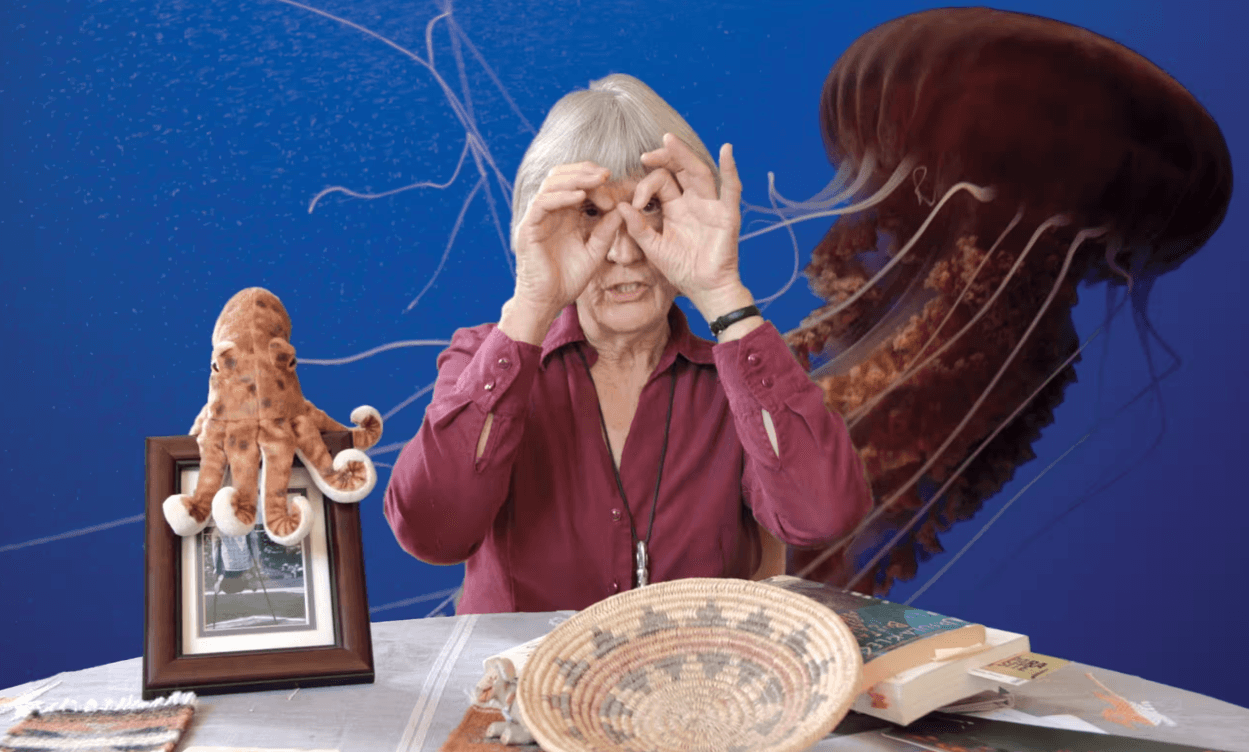

Cyborg feminism, in Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto (1985),” critiques dominant feminist, socialist, and materialist theory. Haraway’s cyborg is a postmodern figural device, deconstructing human/machine, nature/culture, and organism/technology dualisms. Her manifesto dreams up a world beyond essentialist terms, criticising mainstream feminist accounts in terms of biological determinism.

This essay examines cyborg feminism within the context of Haraway’s manifesto, its feminist critique of mainstream feminism, its intersectional focus, and its applicability today in gender, technology, and virtual worlds.

The cyborg as a feminist metaphor

Haraway presents the cyborg as a hybrid being—a cybernetic animal who is both machine and organism. Haraway argues that cyborgs break down the rigid binaries on which Western philosophy has long been built, such as human/machine, male/female, and nature/culture. Hybridisation is a potent metaphor for reconstituting identity beyond essentialist terms.

In mainstream feminist theory, identity has been based on the biological body, fixating on static conceptions of womanhood. The cyborg rejects such essentialist notions, offering instead a more fluid, mobile, and technology-enabled conception of gender.

Haraway’s manifesto is in counterpoint to the hegemonic feminist thought of the 1980s, much of which was founded on the universal “woman’s experience“. Instead, Haraway argues that identities are discursively constituted, socially, economically, and technologically. The cyborg metaphor allows for a more inclusive feminism that acknowledges the heterogeneity of the experiences produced by race, class, and technology.

Intersectionality and the critique of essentialism

Cyborg feminism is on the same side as postmodernism and posthumanism criticisms of essentialism. Essentialist feminist theory presumes an essential female self based on biology, which Haraway rejects as a limiting and exclusionary framework. Cyborg feminism is rather allied with intersectional feminism since it recognises that gender oppression is bound up in intricate ways with race, class, sexuality, and disability.

Haraway’s work is an argument against the notion that feminist theory must turn science and technology into patriarchies. Radical feminist theory has asserted that technology inherently undergirds male control (of reproductive medicine and of surveillance technologies), but for Haraway, technology can become vulnerable to becoming the place where feminism’s liberation lies. The use of the metaphor of the cyborg permits feminism to envision identification with, as opposed to estrangement from, technology. She envisions a future when women and other oppressed groups might use technological advances to reinscribe their identities against dominant forms of oppression.

Cyborgs and the erasure of gender binaries

Perhaps the most extreme implication of the cyborg is that it has the ability to destabilise the hard and fast male/female binary. Feminist theory will tend to reinscribe the male/female binary, even as it attempts to bestow rights upon women. Haraway’s cyborg offers an alternative model of identity based not on biological sex. Under this model, gender is a commodity that can be manipulated, reworked, or even eliminated by technology.

This perspective is consistent with contemporary discussions of gender fluidity, transgender identity, and non-binary identities. Medical and technological advancements, such as hormone therapy, prosthetics, and artificial intelligence, have also increasingly dissolved boundaries between biological and artificial bodies. The cyborg, therefore, is a theoretical tool for understanding the evolving nature of identity in the digital age.

The politics of the cyborg: Beyond humanism

Cyborg feminism is also related to posthumanism, which is a postulate that is critical of the dominance of the human subject in Western philosophy. Posthumanism criticises anthropocentrism and asserts that human beings are situated in an intricate web of relations with non-human agents like animals, machines, and artificial intelligences.

In an age where technological advancement increasingly makes up for human existence, Haraway’s cyborg remains a feminist, powerful, and tenable symbol. It calls for a future where borders are penetrable, categorisation is subverted, and identities are realised through agency and not biological determinism. As Haraway famously asserted, “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess“—a statement that remains valid even today in feminist and posthumanist theory.

Haraway’s cyborg is also a part of this posthumanist challenge to the extent that it suggests that human identity no longer becomes fixed or distinguished from technology.

By dismissing the canonical humanist narrative, Haraway resists patriarchal, capitalist, and colonialist structures that have long bound humanity as one and exclusive. The cyborg, by contrast, is multiplicitous, hybrid, and fluid, which overthrows the notion of a stable universal subject. This vision has profound political ramifications because it calls us to reimagine citizenship, labour, and agency in the era of technology.

Cyborgs in popular culture and digital feminism

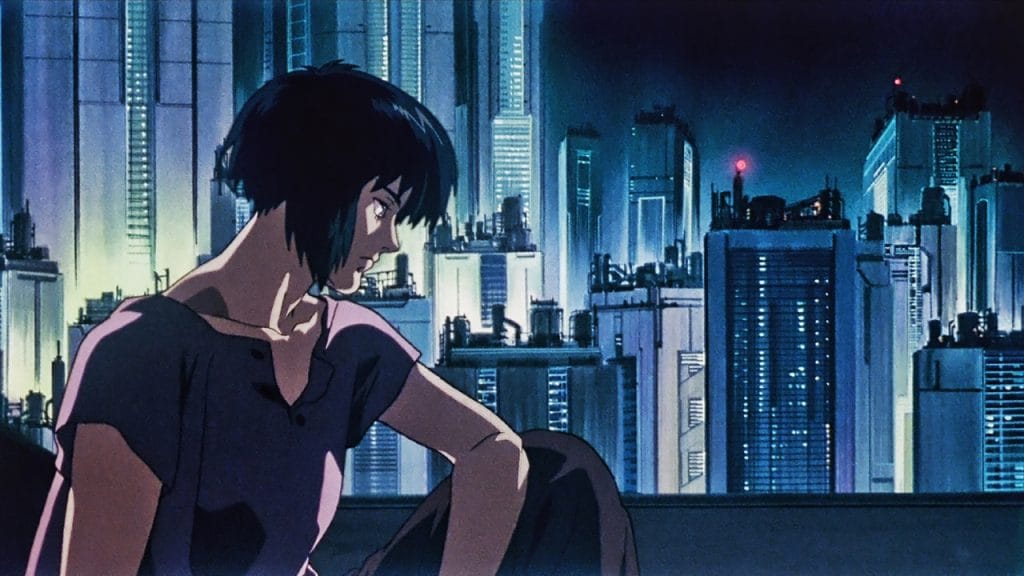

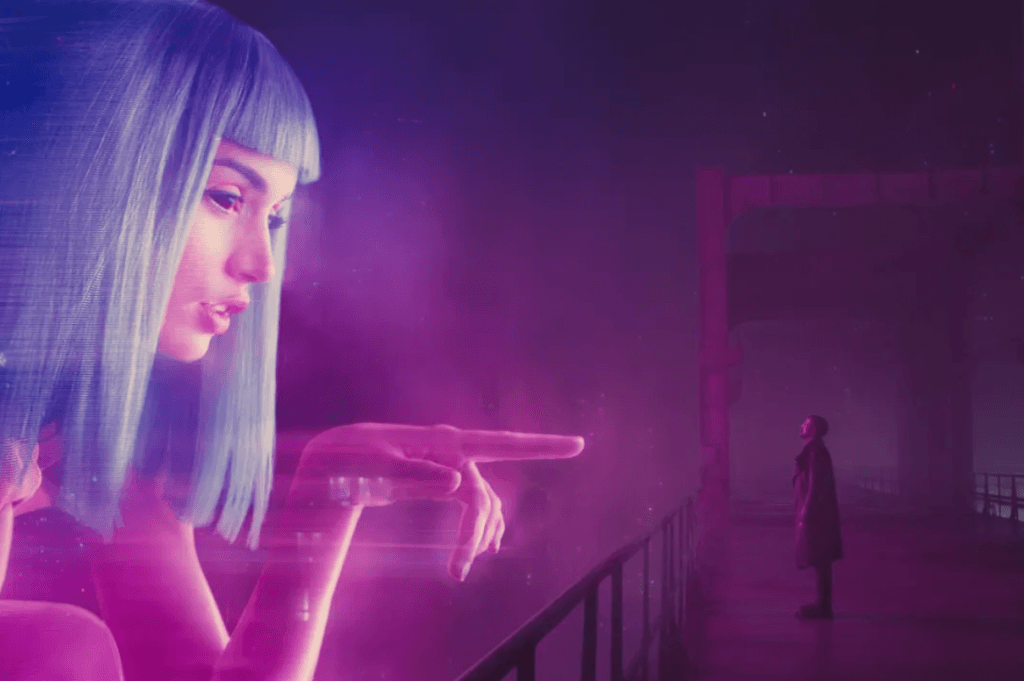

Haraway’s cyborg has also become a shared cultural currency, informing gender and identity constructions in literature, film, and digital media. In science fiction, the cyborg characters of Major Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell and the replicants in Blade Runner erase boundaries between human and machine, disrupting identity coherence. These fictions address broader anxieties about being tricked by technology and offer sites for feminist rethinking of self.

The advent of cyberfeminism, net activism, and cyberfeminism echoes in Haraway’s technology utopia as a political site of resistance. Social networking sites, virtual reality, and computer art provide new spaces for feminist discourse and identity formation. The internet itself is a cyborg universe where identities are formed, broken, and remade in real time. But these virtual worlds also carry new dangers, such as surveillance capitalism, cyberbullying, and algorithmic bias, to which they must be subjected repeatedly in feminist scrutiny.

Critiques and limitations of cyborg feminism

Despite its subversive potential, cyborg feminism has been criticised on a range of grounds. Some have complained that Haraway’s rejection of essentialised identities does away with the worlds of experience of oppressed women. For example, Black feminists and Indigenous scholars have pointed out that material conditions such as racism and colonialism cannot be completely unmade by metaphor. Although Haraway’s manifesto is useful in dismantling Western dualisms, perhaps it does not sufficiently detail how technology is incorporated into racial and economic systems of domination.

Furthermore, while the irony and humour of Haraway’s funeral oration have some critics saying that they may detract from the seriousness of political struggle for feminist activism, even if this hybrid vision of the cyborg is appealing, the cyborg cannot provide us with practical weapons to fight against patriarchal and capitalist power structures. Thus, cyborg feminism must be augmented by more materialist and intersectional activist perspectives.

Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto is a foundational critical feminist work, and it is an account of gender, technology, and power intersections. The cyborg substitutes essentialist identity, validates intersectionality, and presents a posthumanist critique of anthropocentrism. Its influence is not just in the academy but also in digital culture, science fiction, and activism today. But as the technology develops, there also must be fresh feminist thought in response to the political and ethical issues of digital surveillance, machine learning, and biotechnologies.

Cyborg feminism, as much a valuable intellectual resource, must be rethought anew in the face of fresh struggles against injustice and inequality.

In an age where technological advancement increasingly makes up for human existence, Haraway’s cyborg remains a feminist, powerful, and tenable symbol. It calls for a future where borders are penetrable, categorisation is subverted, and identities are realised through agency and not biological determinism. As Haraway famously asserted, “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess“—a statement that remains valid even today in feminist and posthumanist theory.

References:

- https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fictionnownarrativemediaandtheoryinthe21stcentury/manifestly_haraway_—-_a_cyborg_manifesto_science_technology_and_socialist-feminism_in_the_….pdf

- https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-42681-1_3-1

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/20/donna-haraway-interview-cyborg-manifesto-post-truth

About the author(s)

Faga Jaypal is a final year history student at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, with a keen interest in intellectual history, gender and sexuality studies, social justice, and cultural studies. Passionate about literature, books, and museums, he combines his love for storytelling with academic research. Aspiring to become a teacher like Mr. Keating, he seeks to explore history through diverse narratives.