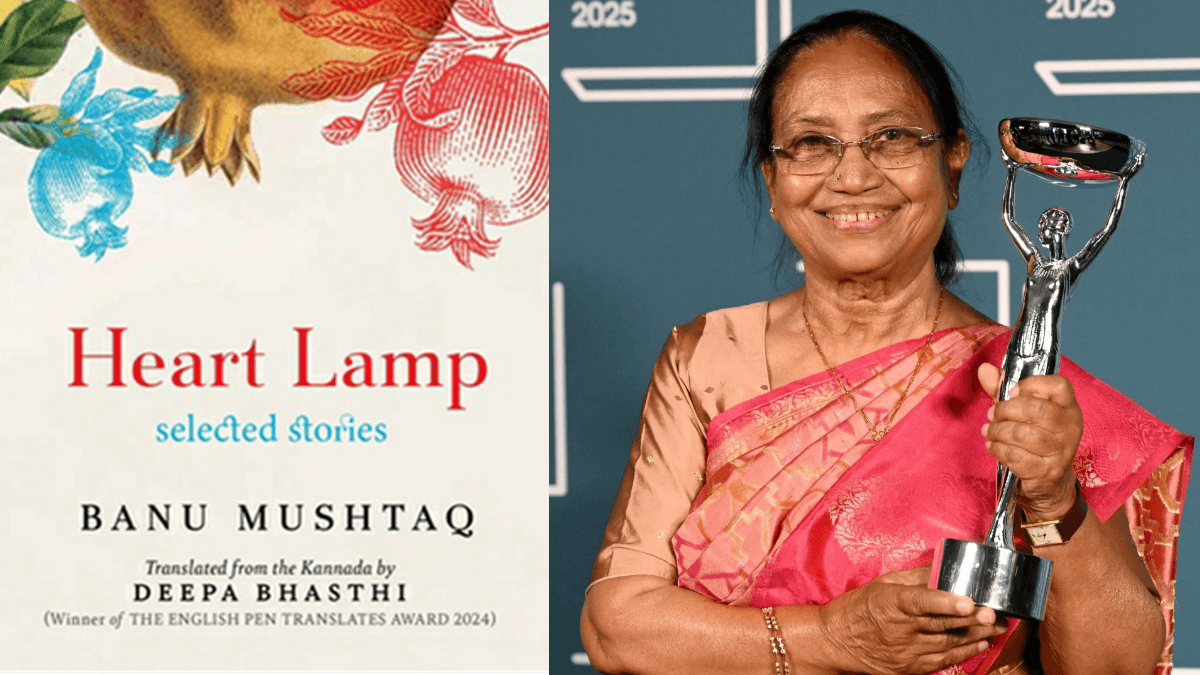

It was never intended that Heart Lamp be a book. Perhaps that is why it is so astounding that it managed to win the Booker Prize. The book explores the lives of Muslim and Dalit women over twelve stories that were written by Banu Mushtaq, a writer, activist and lawyer from Karnataka over thirty years.

Heart Lamp is the first Kannada book to be nominated for the prestigious International Booker Prize, and it was also the only short-story collection that was nominated this year. It was translated by Deepa Bhasthi and her translation won her the English PEN Translates award in 2024.

The book’s inherent ‘Indianness’

It is somewhat undeniable that this book earned the Booker, its tone in itself is distinctive. The stories in Heart Lamp are seeped in the complexities of gender, faith, familial duty and personal longing. Mushtaq’s narratives are filled with rebellion, often revealing of the unspoken tensions simmering between the surface of a seemingly mundane domestic life.

Heart Lamp has drawbacks – Mushtaq has the tendency to introduce too many characters too quickly in almost every single story but perhaps it reflects the drama and intertwining lives of Muslim lives in Karnataka, the possible infective poison of codependency and abuse.

Mushtaq doesn’t rely on overt drama or sweeping statements. Instead, her characters live between the silence between words: women navigating marriage, widowhood, desire, community judgement and often even resignation.

The translation process of Heart Lamp appears to be fascinating. One will not find footnotes or an index; indeed Heart Lamp invited readers to immerse themself into a new cultural context and put in the work. Bhasthi retains the lyrical restraint of Mushtaq’s prose allowing stories to breathe in their original emotional register. Moreover, she preserves words and phrases in the original Kannada, translating Heart Lamp, as she has said in an interview with The Scroll, ‘with an accent‘.

Moreover, she preserves words and phrases in the original Kannada, translating Heart Lamp, as she has said in an interview with The Scroll, ‘with an accent‘.

This seems to be fully true. You can feel the colloquial Indianness reek from the book, and phrases like “Arrey” and “No” can be seemingly informal at times, but it doesn’t take away from the gut-wrenching poetic experience of reading the book. The unfiltered style also escalates the sociopolitical undercurrents of her stories, forcing the reader to immerse themself in what it must be like to live in the very bones of the characters portrayed.

Max Porter, the chair of the International Booker Prize committee, said, ‘Unlike many translations that seek to appear completely natural in the new language — an invisible translation so to speak — this is something different. This is a translation that celebrates moving from one language into another. It contains a multiplicity of Englishes. It is a translation with a texture. It is a vibrant, radical, extraordinary book.’

It also speaks about reproductive rights, a fairly important but subdued conversation, especially when we consider the lives of women living in rural India.

The stories in Heart Lamp

The titular story is perhaps one of the most beautiful. It speaks of heartbreak, perhaps a seemingly ordinary issue that everyone encounters once in their life, but the absolute neglect that the protagonist, Mehrun, faces is soul crushing. It also puts privilege into perspective: several of us are heartbroken in urban cities, with fast paces distractions and our friends and families to ground us, to show us that there is more to life, but for Mehrun, she has given her entire existence, her soul to her husband, and his decision to choose someone else leaves her empty of thought, and rationality. It almost makes the reader feel that it is possible to be driven mad after heartbreak, it is possible to lose sight of oneself completely.

In ‘Stone Slabs for Shaista Mahal’, Mushtaq grapples with religious patriarchy taken at face-value, head on. There is a comparison of one’s husband to one’s God, but not in how when we love someone, we devote ourselves to them, merely how women must subjugate themselves to their husbands. The protagonist, Zeenat, talks about how husbands are second only to Allah, and speaks of the illusion of love – how Shah Jahan created the Taj Mahal for his dead wife. The question remains of coure, would he have cared enough to do that whilst she was still alive? We must take into consideration how marriages and partnerships truly work, and how many women are privileged enough to be in a partnership, instead of being suppressed.

In another absurd tale, ‘A Decision of The Heart’, Mushtaq speaks about a woman’s irrational jealousy of her mother-in-law; how her husband, Yusuf, chooses to sleep at his mother’s house ever so often, choosing the sanctity that his mother can provide over every bit of chaos infused with love that she provides to her husband. The wife’s resentment to Yusuf’s widowed mother leads to scenes of violence that are unfathomable to forget till Yusuf decides to get his mother remarried. The story is rich in humour and highlights the importance of how we tend to let the “masses” influence our decisions, oftentimes forgetting what we want as individuals entirely.

‘Red Lungi’ winds up being a grotesque story. We often consider motherhood to be something divine, a way of existence that all women year for. Sometimes, it just makes us tired. The story revolves around Razia, a woman forced to take care of not only her own raucous children, but the children of her in-laws. Driven almost mad by the relentless noise that they all innocently make during the summer holidays, she decides to organise a mass circumcision of her own children but also several boys in the village.This brings to light inequality, and how poverty is bound sometimes, to make us all wicked.

In the dozen stories of the book, Banu Mushtaq poignantly captures the wearisome lives of Muslim people in Karnataka.

In the dozen stories of the book, Banu Mushtaq poignantly captures the wearisome lives of Muslim people in Karnataka. The humour is both dry and gentle, with several shades of emotion.

One thing must be said about Heart Lamp. Even if the translation seems a bit odd to the reader, the book makes you stop and think. Perhaps, that is the greatest compliment of all.

About the author(s)

Treya covers art, culture, climate and the environment. She has aspired to be a journalist ever since she was little. She has reported for The Hindu and Deccan Chronicle among others and explores how feminism takes root in everyday life by leading sessions with young people on gender, digital safety and the "good girl" syndrome.