In a recent historic and landmark judgement, one that could ripple beyond Kerala and can have a resounding impact on the institutional visibility of the queer community, the Kerala High Court recently ruled in favour of a writ petition filed by a transgender couple seeking the issuance of a birth certificate for their child which mentioned them as “parent” rather than “mother” and “father”.

Stating the concerns raised as valid, the single Judge Bench of Ziyad Rahman A.A., J., held that the issuance of a certificate in the format as prescribed under the provisions contained in the Registration of Births and Deaths Act, 1969 (RBD Act) and Kerala Registration of Births and Deaths Rules, 1999, can cause severe difficulties to the child in life ahead. The Court also asserted that the laws that are not in line with societal changes need to evolve, and the Court must intervene to address the concerns of the concerned parties.

Birth certificates being foundational documents determine access to a host of rights. Thus allowing the use of gender-neutral terminology, this ruling holds significant importance as it challenges one of the many structural ways the state invisiblises the queer community.

The case in detail: challenging the binary institutional framework

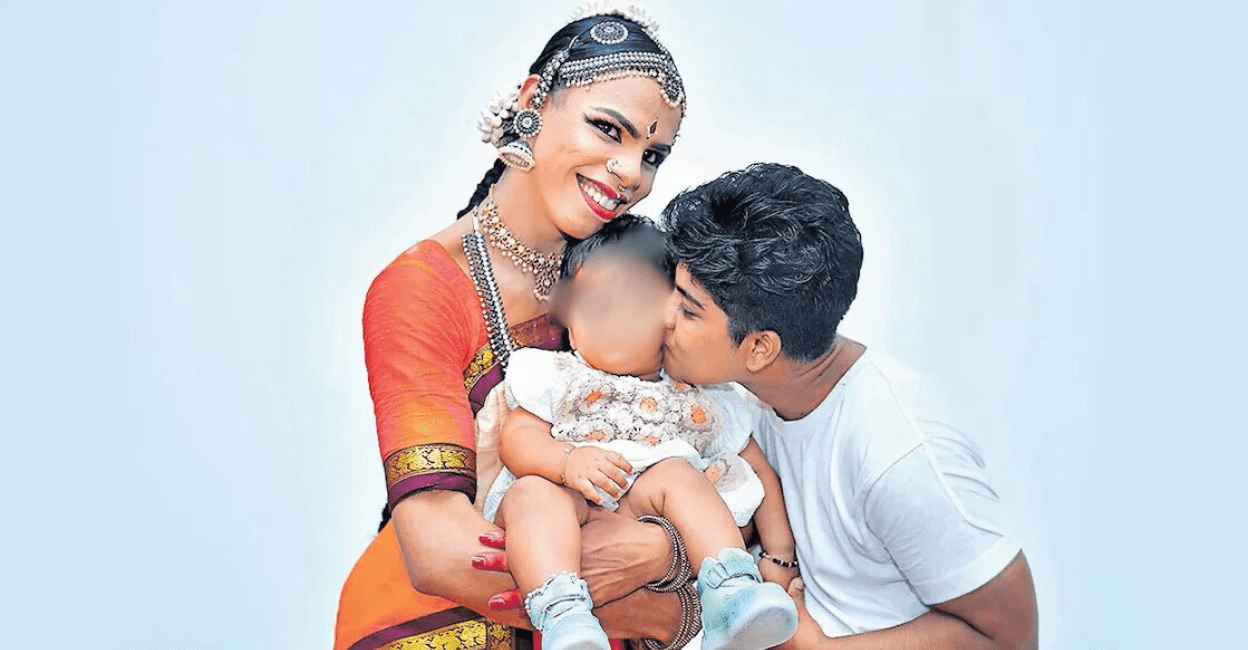

The couple, Ziya Paval (transgender woman) and Zahad (transgender man), had made waves back in 2023 when they became the first known transgender couple in India to have a biological child. Upon birth the Kozhikode Corporation issued a birth certificate that listed Zahad as the “mother (transgender)” and Ziya as the “father (transgender)”, ignoring and contradicting their self-identified genders. The couple felt distressed, stating that such a discrepancy could create serious problems in the life of the child—with regards to identification documents and school admission— since the biological mother of the child identified herself as a male under the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, and was living as a male member of the society.

They approached the Kozhikode Corporation to issue a new birth certificate describing them simply as “parent” rather than mother and father or mentioning their gender.

The Corporation dismissed their request, stating that the certificate was prescribed in accordance with the format contained in the RBD Act 1969 and the Kerala Registration of Births and Deaths Rules, 1999, which only accommodates the traditional binary nomenclature. The couple’s request was not entertained, as the corporation held that there were no other statutory provisions under which they could issue an alternative gender-neutral birth certificate. This decision led the couple to file the writ petition seeking a legal route to reinstate their fundamental rights of equality and the right to self-perceived gender identity as stated under the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019.

This decision led the couple to file the writ petition seeking a legal route to reinstate their fundamental rights of equality and the right to self-perceived gender identity as stated under the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019.

‘Since scientifically there’s some contradiction in the fact that males give birth to a child, the petitioners requested the authorities to avoid the names of the father and mother but simply write ‘Parent’ to avoid further embarrassment which the third petitioner (child) would have to face during her lifetime, viz., school admission, Adhar Card, PAN Card, Passport and various other documents including job and connected matters,’ the transgender couple had explained in their petition.

The apprehension of discrimination based on lived realities of transgender individuals

The Kerala Court evoked the National Legal Services Authority v. Union of India (2014) judgement where the Supreme Court legally recognised the “third gender”/transgender persons and ruled that they are entitled to the fundamental rights and protection under the Constitution. Represented by Padma Lakshmi, Kerala’s first transgender lawyer argued that the rejection of their request violated their fundamental right to equality under Article 14 of the constitution.

The Court maintained that the grievance raised by the couple can not be sidelined since the parental status of the couple was totally in contradiction to the life pursued by them presently. Thus, the confusions and prejudices, as perceived by the couple, in prospect were genuine and very likely to occur.

The Court also adjudicated that even though the child—the recipient of the birth certificate— was not a transgender person, his identity was linked and inseparable from that of the parents, who are a transgender couple, thus providing him equal protection under the Transgender Persons Act 2019.

Legal precedent and the evolving nature of society

Further, the court stated that the law cannot remain static, and the laws need to evolve in accordance with the changes in the society and lifestyle of people. This was consolidated by referencing the Supreme Court verdict in the Badshah v. Urmila Badshah Godse (2014) judgement, where the Supreme Court had addressed the importance of adopting different approaches in “social justice adjudication” and “social context adjudication” when interpreting laws.

This meant that courts need to interpret the legal meaning reflecting the lived realities rather than being congested by the rigid and outdated categories. This statement signified the importance of purposive interpretation of existing laws to accommodate arrangements that usually expunge the queer community, thus allowing one to look beyond cis-heteronormativity.

The Court also pointed out that the RBD Act was framed considering the binary concept of gender, and there was no concept of legal recognition of the third gender.

The Court also pointed out that the RBD Act was framed considering the binary concept of gender, and there was no concept of legal recognition of the third gender. It held that necessary modifications could be made in appropriate cases where the interests of the transgender persons were involved. It also held that when statutory language does not account for the societal transformation, courts have a duty to intervene and redress the genuine concerns, especially when no third-party or institutional rights are being infringed.

Correspondingly, the Court allowed the petition and directed the Kohikode Corporation to issue a birth certificate with a modification of naming the transgender couple as parents, without referring to their gender.

Caste and queerness: A twofold marginalisation

Structural violence and discrimination against the Dalit community by the dominant or “upper” castes remain deeply entrenched, even as they are systematically invisibilised in the public discourse. Nearly 60,000 instances of atrocities against Dalits and Adivasis (“Tribals”) were reported by India’s law enforcement agencies in 2021. The National Crime Records Bureau noted that crimes against Dalits and Adivasis increased by 1.2% and 6.4%, respectively, compared to 2020—statistics that reflect only the tip of the iceberg in a deeply casteist society where many incidents to date go unreported and unacknowledged.

This places the Dalit queer community at a great threat of violation and discrimination. Their gender identity does not exist in isolation; it interlinks and intersects with their caste, often heightening the exposure to discrimination and institutional neglect. A 2019 report by a Bengaluru-based nonprofit, the Centre for Law and Policy Research (CLPR), highlighted that Dalit transgender persons face the most amount of violence in school and are particularly vulnerable to sexual violence at work, with 33% reporting sexual assault and harassment at the workplace.

The intersectional and twofold marginalisation of the Dalit transgender people—often invisibilised within the legal and institutional frameworks—is at a vulnerable crossroad.

The intersectional and twofold marginalisation of the Dalit transgender people—often invisibilised within the legal and institutional frameworks—is at a vulnerable crossroad. The queer rights discourse primarily has focused on urban, savarna experiences. This enunciates the importance of placing the caste question at the forefront when discussing queer marginalisation.

The recent judgement by the Kerala High Court represents the rare legal acknowledgement of the complex lived realities of the queer community. The judgement can very likely set the precedent for a more inclusive interpretation of laws by rejecting the hyper-technical formalisation in favour of substantive justice and the evolving nature of the society. With a more nuanced interpretation of the laws, caste can be centred in conversations around the queer marginalisation.

About the author(s)

Reeba Khan is a Political Science student at Delhi University. As a writer and student journalist, she has a keen interest in issues of identity, conflict, and politics of belonging. She writes to remember and to resist