Kerala, so famously called God’s Own Country, is often held up as a model state owing to its high literacy, progressive politics and a history of strong communist movements. But beneath that celebrated image lies a much older, much darker reality: caste. Despite its leftist legacy, casteism in Kerala is still alive and ubiquitous, entrenched in institutions, language and everyday interactions. The state’s temples were once closed to Adivasis and Dalits; schools denied them access; roads were forbidden terrain and even marginalised women’s modesty was exploited and taxed (the very infamous breast tax). Social reformers like Ayyankali and movements like the Sadhu Jana Paripalana Sangham challenged this oppression, demanding education, dignity and land.

This contradiction of modernity draped over casteist practices runs deep in Kerala’s literary world too. For years, Malayalam literature largely ignored Dalit voices. When it did acknowledge them, it was often through the voyeuristic gaze of upper-caste writers portraying Dalit lives as either pitiful or exotic. Savarna critics like C.P Achutha Menon weren’t appreciative of the early portrayals of the Dalits in literature as they believed that the emotions of a Dalit hero deserved little attention in literature when compared to their upper-caste counterparts.

It wasn’t until the mid 20th century that Dalit writers in Kerala began breaking ground, writing their truths in raw, unfiltered language. Their literature was not polished to appease the upper castes nor did it abide by their rules. It was angry, honest and unapologetic. Among these voices, Vijila Chirappad stands out, not only as a Dalit writer but as a Dalit woman who speaks from the intersections of caste and gender.

The personal is political, and poetic

Reading Vijila Chirappad’s poetry is like watching through a peephole into the lives of the many Dalit women that exist all around us— as mothers, maids and so many more women who have been forced to make themselves smaller and invisible. Her poems are a mirror that doesn’t flatter, doesn’t romanticise and doesn’t flinch. Vijila’s poetry doesn’t beg for empathy. It dares you to recognise and remember.

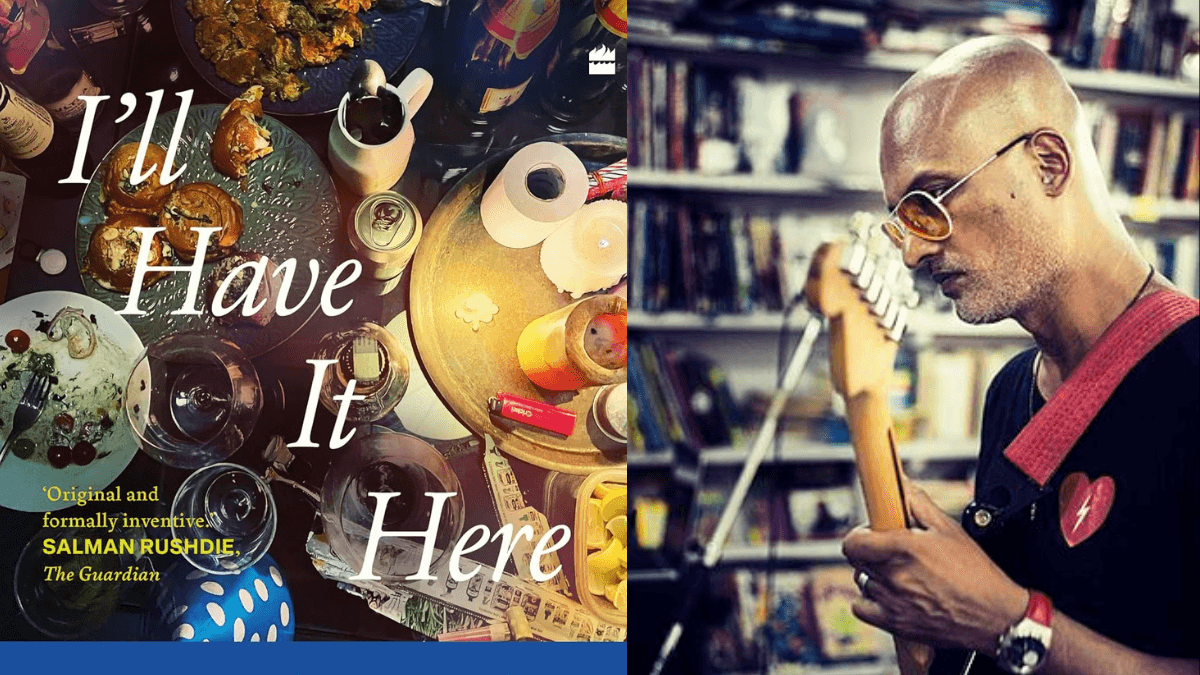

Born in Perambra, Kozhikode, Vijila Chirappad began writing poetry as a student, despite having to fight for every inch of space in a literary world that never expected someone like her to speak, let alone publish. Despite these challenges, Vijila has three celebrated poetry collections to her name: Adukala Illatha Veedu (A Home Without a Kitchen, 2006), Amma Oru Kalpanika Kavitha Alla (Mother is Not a Poetic Figment of our Imagination, 2009) and Pakarthi Ezhuthu (Copied Notes, 2015).

Born in Perambra, Kozhikode, Vijila Chirappad began writing poetry as a student, despite having to fight for every inch of space in a literary world that never expected someone like her to speak, let alone publish.

Speaking about her initial struggles for getting published, she said, ‘You see publishing in itself is an arduous process. And since I’m not even an adopted child of mainstream society, you can guess how hard it has been for me. Yet not even once did I think of giving up. I have had to literally fight to get to wherever I find myself now in the poetic sphere‘.

In a literary tradition that often romanticises suffering or turns it into abstract metaphors, Vijila does something radically simple by laying bare the naked truth in its most raw and realistic form. Through her words we meet the Dalit woman in her fullness: tired, angry, defiant, tender and most importantly, real. Her poems are soaked in the normalised routine of caste and gender violence in Kerala, a state often praised for its progressive politics but which, like much of India, remains deeply scarred by Brahmanical patriarchy.

A Dalit voice without apology

In her poem ‘A Place for Me’, Vijila writes about a woman who loses everything—her home, her land, her wealth—but clings to her alphabets and relationships like lifelines. ‘The plentiful bowl of relationships,‘ she says, offers more nourishment than wealth ever could. This isn’t mere sentimentality but rather, a declaration that Dalit survival is not just physical or personal but collective and intellectual.

She echoes the ideas put forth by Ambedkar through the speaker of the poem who, despite having lost every penny she owned to the upper-caste creditors, holds dear the wealth provided by her education. Ambedkar argued that education was instrumental in changing the lives and social status of the untouchables. Moreover, the poem is also a dissent against the upper-caste who, throughout centuries, have denied Dalits access to education and thereby, a life of dignity.

This is a recurring theme in Vijila’s poetry— how language and memory become tools of resistance.

This is a recurring theme in Vijila’s poetry— how language and memory become tools of resistance. In a society where Dalits have historically been denied access to literacy and narrative power, the very act of writing becomes an act of reclaiming and revolt. Her words are raw not because they lack embellishments, but because they choose not to perform or bend for an upper-caste gaze.

On mothers, labour and the everyday

Mainstream Indian poetry often portrays the mother as a mythical nurturer— serene, saintly, wrapped in sarees of metaphor. But the mothers in Vijila’s poetry is portrayed in their truest and rawest forms. They go about their lives earning a living, toiling day in and day out. In ‘She Who Flew Afore’, she writes:

‘In our home

There is no TV

No fridge

Neither mixer

Nor grinder…

Yet my mother knew

How to operate these

Much before I did.

Because…

Like in Madhavikutty’s stories

She is Janu—

The servant.’

This mother isn’t a muse. She is far from the way mothers are portrayed in mainstream Indian media owing to the upper-caste narrative. She exists not in an imagined nostalgia but in the real and often unacknowledged labor of Dalit domestic workers. Vijila here is not only calling out casteist portrayals in upper-caste literature but also asserting visibility to these women and their lives. The mothers Vijila has known are not ornaments in family dramas. They are the ones who woke up before the world opened its eyes, worked in homes that weren’t theirs and came back to feed families from stoves that ran on hope and borrowed fuel.

In ‘Wasteland’ (Purampokku), Vijila exposes the everyday casteism that haunts even the most mundane moments. The poem tells the story of Chandrika, a Dalit woman who can only enter certain homes through the back door. She, a human being and the fish from the market have the same entrance to a house. This comparison is brutal and deliberate. It captures how caste not only decides where you can go, but how you are seen, touched and tolerated.

The poem ends with Chandrika listening to the Indian pledge on August 15—’All Indians are my brothers and sisters‘—a line that becomes worthless in the face of lived discrimination.

The poem ends with Chandrika listening to the Indian pledge on August 15—’All Indians are my brothers and sisters‘—a line that becomes worthless in the face of lived discrimination. The poem doesn’t ask for sympathy, it demands that the reader confront the hypocrisy of a society that chants equality while maintaining invisible walls of caste.

Autobiography of a bitch: her rage and defiance

Perhaps one of Vijila’s most powerful poems is ‘Oru Penpattiyude Athmakadha’ (The Autobiography of a Bitch). It’s a searing, sarcastic and brutally honest portrayal of how society sees Dalit women—not as people, but as disposable and dirty.

‘Oh world, world

Our kind

Hides in the backyards

Eyes fixed on leftovers

Lies curled up in back-verandas

Finds solace in darkness.‘

Here, the speaker compares herself to a street dog, reflecting how caste and gender hierarchies dehumanise women like her. But there is no self-pity. Instead, there is rage and irony. The poem calls out not just the violence from outside the community but also the internalised shame within. The lines are a rallying cry for Dalit women to reject the conditioning that tells them they are not enough, that they are not beautiful enough, not worthy enough, not human enough.

A fierce Dalit woman poet breaking poetic traditions

Vijila’s poems are postmodern in the best way. They break the rules of poetry because those rules were never written for people like her in the first place. She writes about kitchen rags, lice, leaking roofs and bitches. The tone in her poems is often filled with irony. She uses the mundane to represent the lives of the downtrodden and oppressed.

Kerala’s so-called progressiveness often masks the deep roots of casteist and patriarchal values. As Vijila has said in interviews, ‘Casteism is embedded in the subconscious of Kerala society.’ Her poems expose that subconscious. Vijila Chirappad’s poems are not just verses. They are words of survival, protest and vision. They demand that we don’t just listen but learn. They insist that Dalit women should not be just passive victims but fierce historians of their own lives.