In the 1980s, radical feminist scholars Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin drafted a U.S. Civil Rights Ordinance letting, women, and others, harmed by pornography sue its producers—not to ban it but to seek justice. Although the ordinance was passed in Indianapolis, courts eventually struck it down due to concerns regarding the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Yet, the boldness of their stand of suing the porn makers sparked one of the most intense debates within feminist circles—one that continues to echo in today’s digital age.

Porn and power

Bernard Williams has given the definition of pornography as a representation of sexual activity that is meant to arouse. Hence, sexy lingerie is not pornographic since it doesn’t represent sexual activity even if it is intended to arouse. Andrea Dworkin believed that pornography was not simply about sex; it was about power. She argues that male violence against women is both the most shocking and the most common aspect of patriarchy, portraying heterosexuality as an institution of male dominance and female submission.

Catharine MacKinnon further argued against the idea that free speech protects pornography. Rather, she believed that it is pornography that silences women, emphasising that they are inferior to men, reducing them to sexual objects and reinforcing structural inequality.

Andrea Dworkin believed that pornography was not simply about sex; it was about power. She argues that male violence against women is both the most shocking and the most common aspect of patriarchy, portraying heterosexuality as an institution of male dominance and female submission. Both Dworkin and MacKinnon believed that mainstream porn “dehumanizes women” and reinforces this unequal structure.

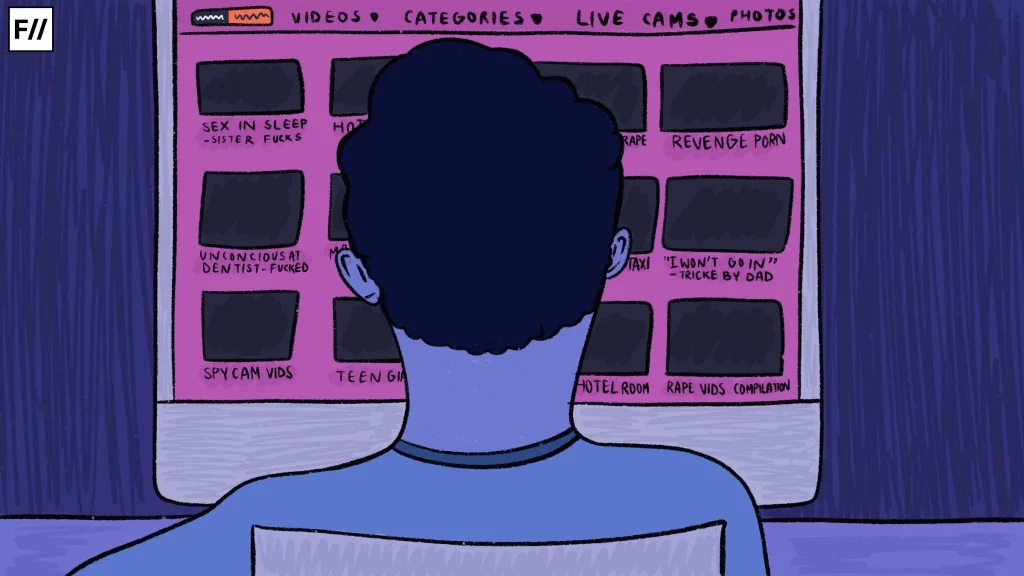

Their core argument centred on sexual hierarchy—a system where men dominate and women are expected to submit. Both Dworkin and MacKinnon believed that mainstream porn “dehumanizes women” and reinforces this unequal structure. According to them, much of the pornography depicts women as enjoying abuse or humiliation, which not only normalises such violence but also contributes to the real-life abuse women face in society.

Porn is not just entertainment, but real harm to real women

Dworkin and MacKinnon argue that the harm caused by pornography is not just theoretical; rather, it causes real harm to real women who appear in it. A disturbing example is Linda Lovelace, who appeared in one of the best-selling pornographic films, Deep Throat, and later described how she was trapped, beaten, and forced into the film by her husband, Chuck Traynor.

After leaving Traynor in 1973, Lovelace became a vocal critic of the industry:

‘When you see “Deep Throat”, you are watching me being raped… There was a gun to my head the entire time.’

Her experience illustrates their assertion that pornographic content is not just an image—it may rest on the physical and psychological abuse of women in its production. Once such content is created and shared, it reinforces the broader cultural narrative that women’s suffering is acceptable—or even erotic.

Whenever pornography shows a woman in a position of humiliation or bondage, Dworkin argues that a real woman has to suffer. And once such images are shared, they not only make people less sensitive to violence but also contribute to a broader culture of misogyny.

Whenever pornography shows a woman in a position of humiliation or bondage, Dworkin argues that a real woman has to suffer. And once such images are shared, they not only make people less sensitive to violence but also contribute to a broader culture of misogyny. MacKinnon similarly argues that the consumption of pornography actively fuels sex trafficking and prostitution. She emphasises that pornography, trafficking, and prostitution are deeply interconnected, all revolving around the use of women’s bodies and the purchase of sex as an experience.

Does porn lead to real-world violence?

This is where the debate gets more complicated. Anti-censorship feminists like Alison Assister and Nadine Strossen accused Dworkin and MacKinnon of being ‘anti-sex’ and creating ‘pornographic sex-panic’. They say that most of the pornography is non-violent and consensual and that laws already exist to criminalise rape and violence. Thus, according to them, the approaches of Dworkin and MacKinnon are misleading.

On the other hand, Dworkin’s supporters argue that it is worth noting that laws against rape are not the same as laws against pornography showing rape. They also point out that these laws are not always used properly and don’t stop violent porn from being made and shared. Thus, there is no clear-cut consensus but two kinds of evidence are offered for this—anecdotal accounts and experimental studies.

Anecdotal accounts state the cases regarding attacks of women or children who were forced to copy pornographic images. For instance, a Native American woman described how two white men who raped her kept talking about a game called ‘Custer’s Revenge’—a pornographic game that glorified sexual violence against Indigenous women. In psychological experiments, US volunteer male college students were made to watch a film per day for 5 days. Some saw slasher films or violent pornography, while some saw non-violent pornography. The men viewing the violent material became increasingly desensitised to the violence, in contrast to those who saw non-violent content.

The feminist pornography debate compels us to confront uncomfortable truths about consent, agency, and the manner in which women’s bodies are often treated as objects. It makes us ask: Is all sexual expression empowering? Who gets to decide that? Can there truly be choice in a world where so many women are still denied basic freedom?

The opponents of censorship still argue that even if some violence is caused by pornography, the correct response is to tackle the violence through education, consent training, and prosecuting actual rape—not to ban the representation. But this begs the question: can representations that normalised violence ever be truly harmless?

Where does this leave us?

The feminist pornography debate remains unresolved and maybe it is not meant to be neatly wrapped up. Instead, it compels us to confront uncomfortable truths about consent, agency, and the manner in which women’s bodies are often treated as objects. It makes us ask: Is all sexual expression empowering? Who gets to decide that? Can there truly be choice in a world where so many women are still denied basic freedom?

In India, where even saying the word “sex” can make people shift uncomfortably in their seats, such conversations become even harder. Add to that the stigma around women’s pleasure, safety, and autonomy, and the debate becomes deeply layered. Here, access to digital porn is easy, but access to sexual education is not. Consent remains misunderstood, and women are still blamed more than protected.

This is why the radical questions Dworkin and MacKinnon asked decades ago still matter. Their words are not comfortable—but they were never meant to be. They demand that we examine the power structures buried in what we consume, even the things we think are private or harmless. Their work shows us that feminism isn’t one-size-fits-all. To truly stand for gender equality, we need to face these complexities, contradictions, and discomforts that come with it.

About the author(s)

Gunn Bhargava (she/her) is a Political Science undergraduate at the University of Delhi and a feminist writer focusing on gender justice, power, and human rights. Her work engages with feminist media, pop culture and political analysis, drawing from her experience with platforms such as Feminism in India, Writing Women and The Women Story. She is keen on contributing to transnational feminist conversations through progressive journalism.