Coconut trees average around 60 feet in height, with a smooth exterior and no branches, making it difficult to pull yourself up. Which is why climbing them requires technique and practice. In states like Kerala, people hire seasoned tree climbers to tend to their coconut trees. However, in Param Sundari, Janhvi Kapoor’s Thekkapetta Sundari Damodaran Pillai, casually and swiftly climbs up one, as if it were a quotidian event. This should tell you everything you need to know about the film.

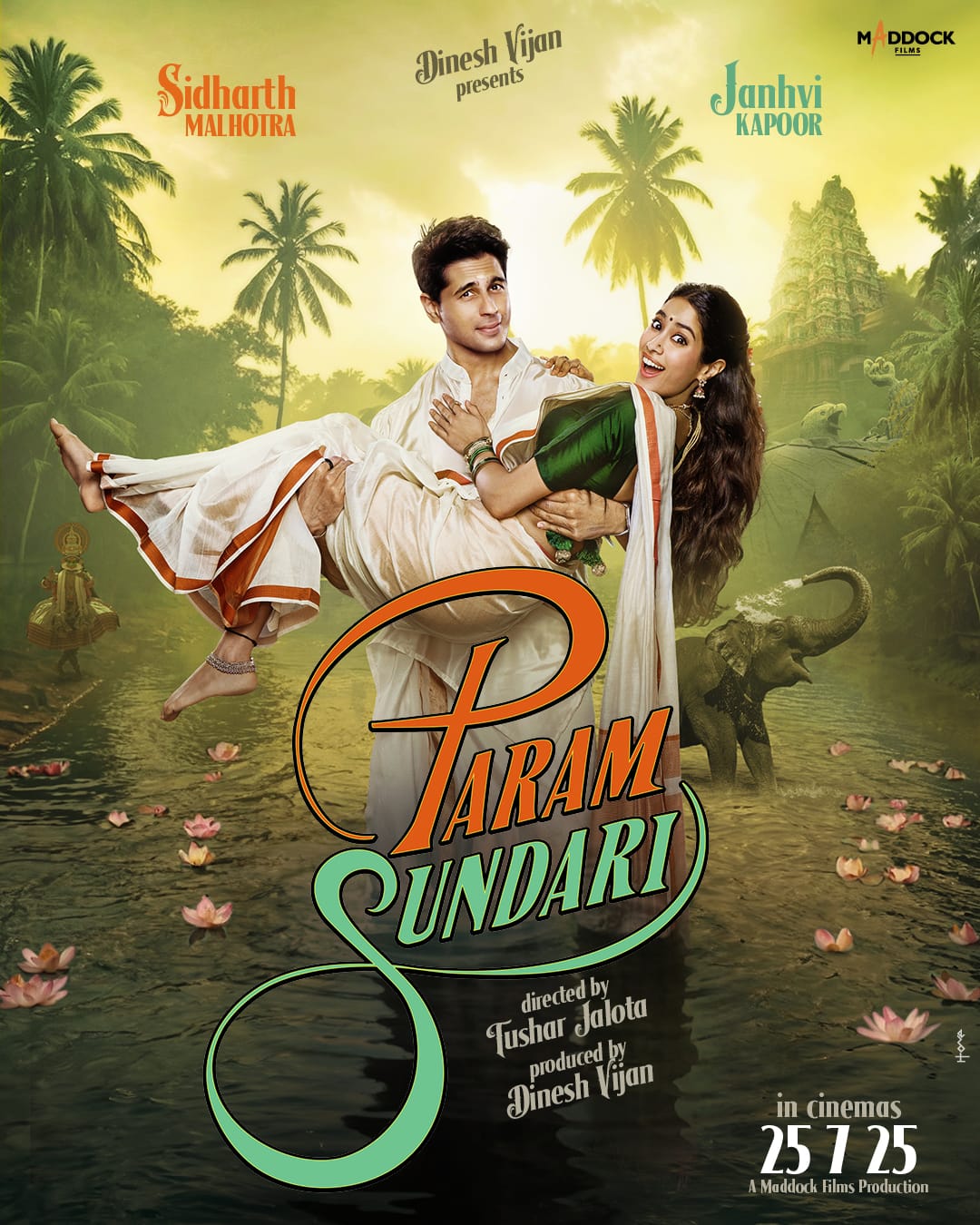

Param Sundari, starring Sidharth Malhotra and Janhvi Kapoor as the titular Param and Sundari, is an uninspired Chennai Express knock-off that draws on the same tired stereotypes as the original and invests more time in caricaturising its South Indian characters than in the plot. Param is a Delhi-based Punjabi investor. He seeks to invest in an app called Find Your Soulmate, which tells him his soulmate is a Malayali woman called Sundari who lives in Alappuzha and runs a homestay.

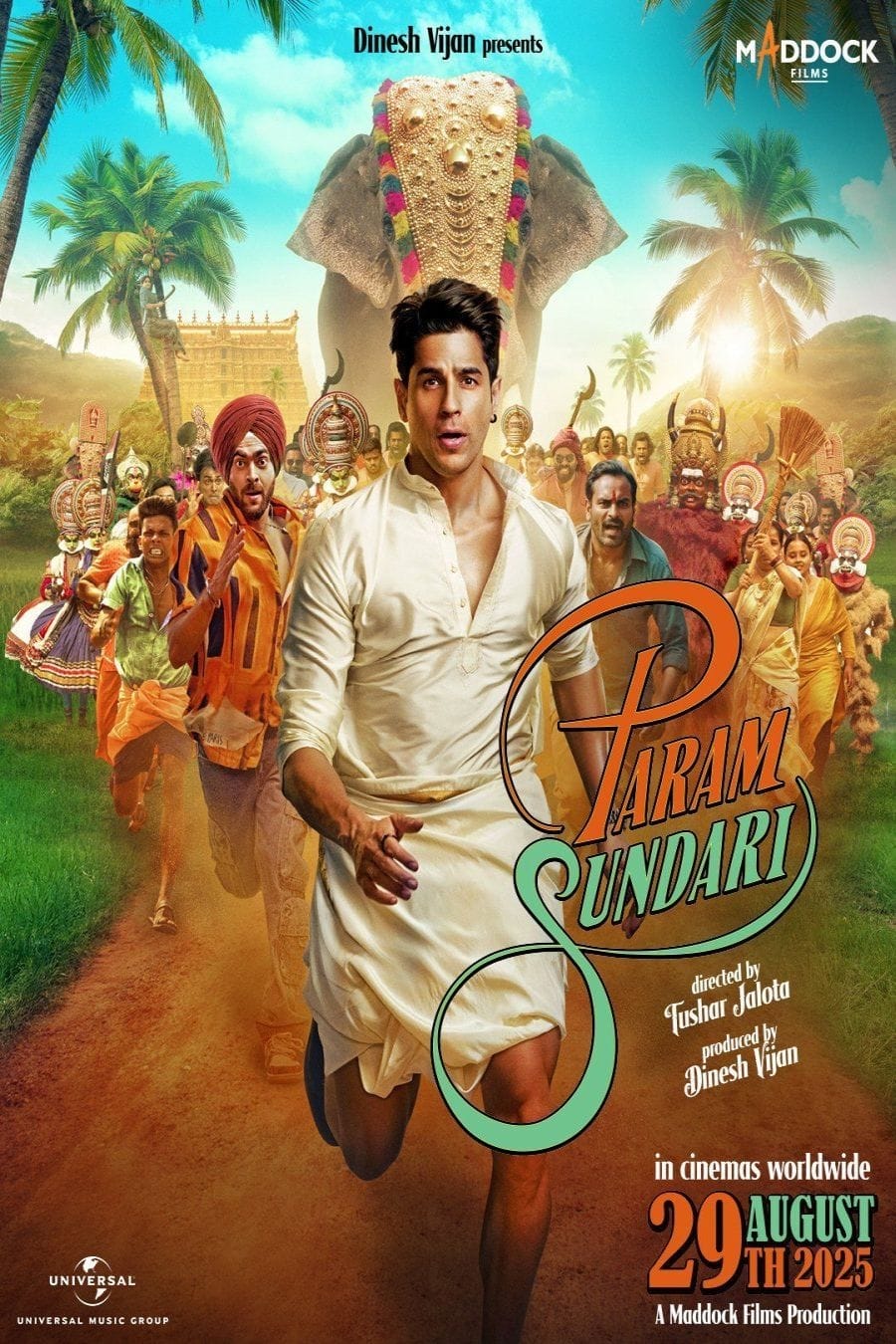

Param and his friend Jaggi (played by Manjot Singh) come to Kerala to meet Sundari, where she raises her sister after her parents’ death. Sundari lives in a place called Nangiakulangara in Alappuzha. Predictably, a North Indian character mocks the name. After all, anything that isn’t North Indian must be funny. Then, he asks if the place is in Africa, because anything “weird” to the North Indian imagination must surely be African.

Sundari’s name reveals a lot, too. In Dil Se‘s ‘Jiya Jale’, picturised on Preity Zinta’s Malayali character, and containing routinely butchered Malayalam wording, the lyrics contain the words ‘chundari vaave (beautiful girl)’. Chundari is a colloquialism for sundari (beautiful). And Sundari Pillai, the film tells us, is the exotic; jasmine-clad; settu-mundu-wearing; Mohiniyattam-performing; hot-headed; and, if we are being generous, Malayalam-speaking, chundari vava of Param Sundari. Sundari is both caricaturised and exoticised.

Thengas, Koduvals, and representation stuck in the 90s

Upon arriving in Kerala, Param and Jaggi’s first brush with Malayalis is a cab driver who is drunk on toddy. As they reach Nangiakulangara, they see communists protesting on the streets. And a man menacingly holding knives and who is presumably Muslim, given the copious amount of eyeliner he is wearing, which, as we all know, is Bollywood for Muslim, directs them to Sundari’s homestay. The men are all portrayed as hoodlums, loitering about and up to no good. This film accurately reflects what Kerala truly is like, or so a Sanghi troll on Twitter would say.

This film accurately reflects what Kerala truly is like, or so a Sanghi troll on Twitter would say.

The first time we see Sundari on screen, she’s dancing. So, we are to believe, she is beautiful, demure, and feminine. That is, until she opens her mouth, then she’s a koduval-wielding (a billhook machete often used to break coconuts), loud, hot-head. Sundari, the film takes great pains to tell us through an exaggerated accent, can’t speak Hindi, and Janhvi Kapoor, you can tell with ease, can’t speak Malayalam.

If the point that our Alappuzha-residing, Mohiniyattam-performing, koduval-owning protagonist is sufficiently exotic wasn’t driven home already, she has a penchant for climbing coconut trees after stressful conversations, has a pet elephant, treats wounds by picking and grinding stray leaves, and does Mohiniyattam in a church.

Thengas (coconuts) also seem to have a central role in the film, because all of Malayali identity and culture can be reduced to coconuts. There are many scenes where coconuts are being picked, Sundari casually climbs coconut trees, she yells ‘thenga’ in frustration, she also says the expression ‘dimaag ka thenga (mind’s coconut)’ when expressing her love for Param, and thengas are also used as weapons.

All that might seem excessive, but it doesn’t end there. In the climax, Sidharth Malhotra makes his big speech atop a coconut tree, climbing which is presumably the grand gesture. Who wouldn’t swoon? Surely there must be something in the plot that warrants this; maybe he was barred from going to her room or their phones were taken away, but no, he just climbs a 60-foot tree for the jollies, and nobody even attempts to explain why. Maybe the makers thought exotic, thenga-adoring Malayalis only accept declarations of love coming from people perched on trees.

Comedy as a front to engage in colourism

On the flight to Kerala, upon seeing a dark-skinned man, Jaggi attempts to speak to him in Malayalam, because surely, the stout, dark-skinned man who isn’t conventionally attractive must be South Indian. Turns out he isn’t. The film isn’t making a point; this is just played for laughs.

Pretty much everyone cast as a Malayali, apart from Kapoor, is dark-skinned. It can be argued that this isn’t colourism because South Indians, on average, tend to be darker. However, an important thing to consider here is, if the makers truly see all South Indians as uniformly dark-skinned, why isn’t Sundari’s part played by a dark-skinned actor? The colourism, then, manifests in two ways: stereotyping all South Indians as having only one kind of skin tone, but simultaneously refusing to allow the beautiful, desirable lead to be played by a dark-skinned woman because dark-skinned in Bollywood still translates to undesirable. So, Sundari can either be a sundari or dark-skinned.

It’s no coincidence that outside of Sundari, the only Malayali character that isn’t dark-skinned is her fiancé Venu (Siddhartha Shankar), and he’s also the only character who isn’t a caricature.

It’s no coincidence that outside of Sundari, the only Malayali character that isn’t dark-skinned is her fiancé Venu (Siddhartha Shankar), and he’s also the only character who isn’t a caricature. If a character isn’t a caricature or comical, then they are played by a fair-skinned actor, which seems intentional.

Param Sundari isn’t meta or self-aware

Param Sundari wants you to believe it’s self-aware, that it’s critiquing ignorance. However, the film does this in an effort to engage in its own xenophobia without accountability. Sundari, we are led to believe, won’t stand for diverse South Indian identities being clubbed under the xenophobic title of “Madrasi”. She’s annoyed when Param mistakes Onam for Pongal and furious when Jaggi says it doesn’t matter one way or the other because it’s all South Indian, therefore, all the same.

When Mohanlal is mistaken for Rajnikanth, Sundari launches into a tirade, informing Param which South Indian actors belong to which states. This could have been effective if the larger point about South Indian culture or identity not being homogeneous hadn’t been reduced and contained to an inane point about celebrities, and also if it hadn’t been delivered by a character who is a caricature herself.

All this begs the question, why make a North Indian-South Indian love story when the writers and creators don’t want to put in the effort to research the culture that serves as the setting of their film? The ridiculously simple answer is: this caricaturised portrayal of South Indians, unfortunately, still sells. And that throws up some hard questions about the xenophobia still prevalent, and normalised, in India. Sundari might tell us all South Indians are not Madrasis, but it doesn’t seem like the makers know this themselves.

Questionable casting in Param Sundari

Before the film was released, there was some uproar regarding the choice to cast Janhvi Kapoor. Janhvi Kapoor isn’t Malayali, but more importantly, she doesn’t speak Malayalam. While it’s true that actors aren’t always cast to play characters with the same linguistic background as their own, the decision to cast a non-Malayalam speaking actor to play a part that requires speaking the language is suspect.

While it’s true that actors aren’t always cast to play characters with the same linguistic background as their own, the decision to cast a non-Malayalam speaking actor to play a part that requires speaking the language is suspect.

Janhvi Kapoor butchers the little Malayalam she speaks in the film. Something she cannot be faulted for because Malayalam is a notoriously difficult language to learn, but the decision to cast her can and should be called into question. And this would never happen the other way round. No Bollywood production would cast an actor who doesn’t speak the language for a Hindi-speaking part.

There is no reason for Param Sundari to be set in Kerala. The plot would have worked fine, set in any other state. The only reason to choose a southern state, especially when no one involved in the production attempted to research the place or culture or look past stereotypes, is that this exotic, alien place can function as a fodder for endless jokes. It’s then hard to believe that this tired, clichéd portrayal of Kerala and Malayalis is only a product of ignorance, and not of intentional xenophobia.

Param Sundari clearly tries to be the new Chennai Express. And this says everything that needs to be said about the film. Chennai Express wasn’t a film with much merit; its entire entertainment value was rooted in its viewers finding xenophobia funny. In attempting to emulate it and applying the same formulae over a decade later, Param Sundari also delivers a 2-hour disappointment.

While the majority of South Indian representation in Bollywood is poor, there are some notable examples of good representation as well. Dil Se, which was released 25 years ago, comes to mind. Param Sundari could have drawn on such films for its inspiration, or simply on reality by acknowledging the multi-faceted, pluralistic realities of Kerala and South India. It could have been an example of good representation of South Indians in Bollywood, but it’s evident from the start that it was interested in no such thing.

The film seeks little more than cheap laughs from the intentionally poor representation of thenga-loving, koduval-wielding, hot-headed Malayalis, and why wouldn’t it? Chennai Express was applauded for the same things a decade ago. As long as ignorance, colourism, xenophobia, and the othering of South India and South Indians sell, Bollywood will always try to cash in.

About the author(s)