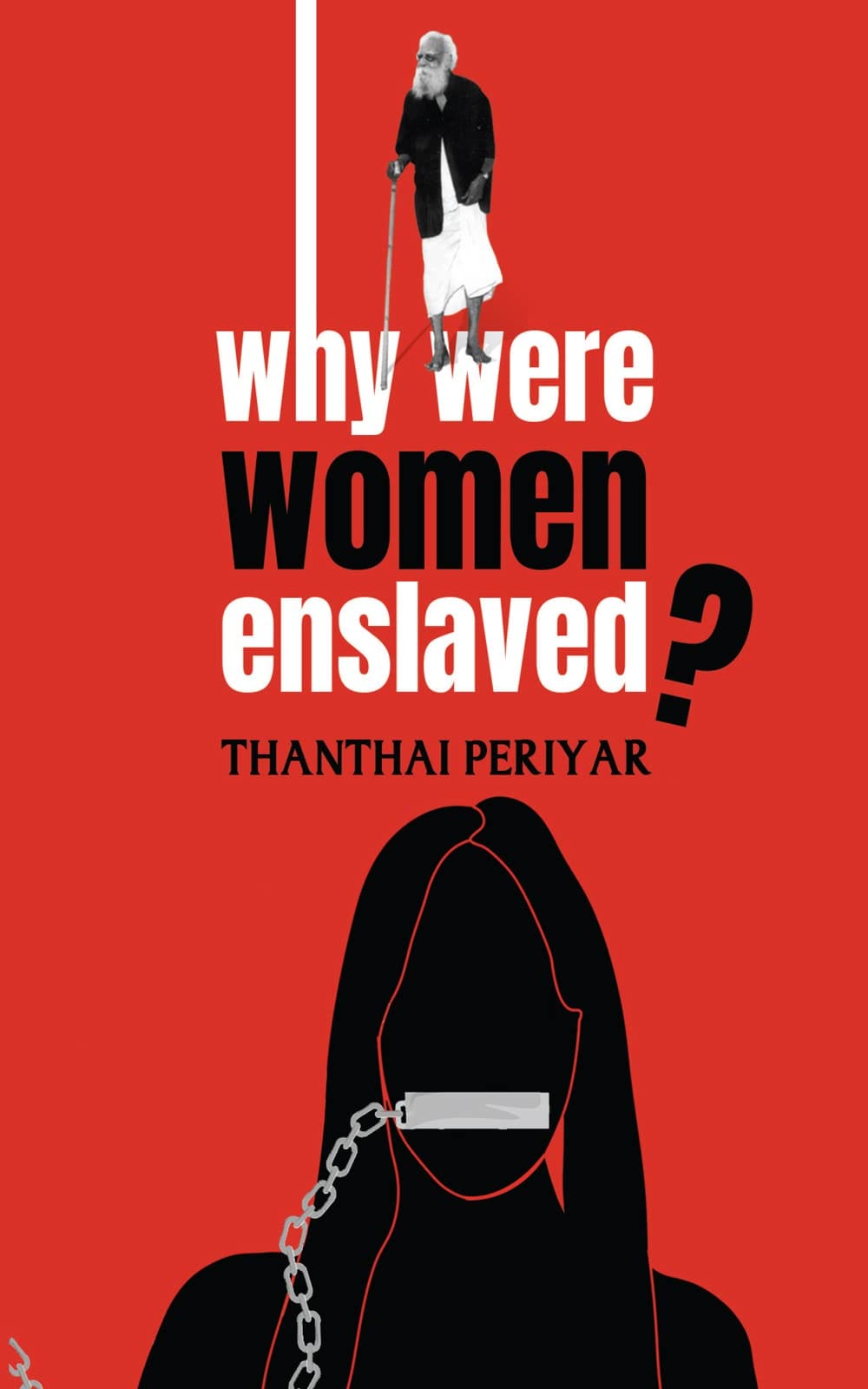

Why Were Women Enslaved? (Pen Yen Adimaiyaanaal?, 1942) was originally written in Tamil by Periyar E V Ramasamy and was translated into English for the first time by Meena Kandasamy. This important work is much more than just a book because it is a revolutionary manifesto that boldly questions the root causes of women’s oppression. Although it was written during the pre-independence period, its message remains powerful today since the struggle for gender justice is still ongoing in the twenty-first century.

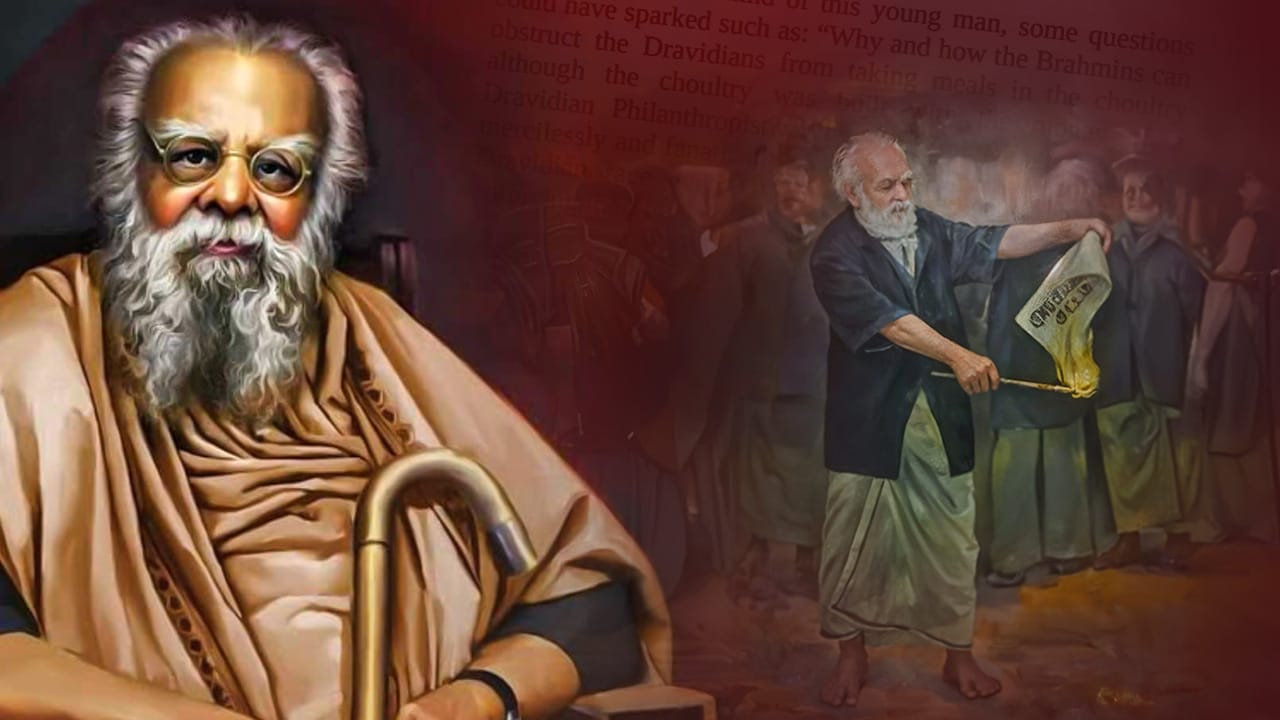

E V Ramasamy, popularly known as Periyar, was one of India’s most radical rationalists and anti-caste thinkers. He advocates that women’s enslavement is not accidental but is built into the structure of society through religion, tradition, and social customs. He insists that true liberation requires dismantling patriarchy at its very foundation. This means not only changing individual beliefs but also transforming the institutions that maintain inequality.

The book reflects Periyar’s feminist views, which are based on rationalism and the belief that all hierarchical social systems, including caste and patriarchy, must be critically examined and abolished. He identified religion, especially Hinduism, as the main tool used to justify and continue the oppression of women. According to Periyar, women in India have never been treated as full human beings but as property whose purpose was to serve men. They were controlled in every part of their lives and denied basic rights like education, property, and freedom.

He argued in the book that the enslaved condition of women is not natural but created and maintained by religious rules, mythological stories, caste discrimination, and male dominance. Today, this book remains a vital text for understanding how gender, caste, and power are connected and why true liberation requires challenging all these systems together.

Chastity as a tool of patriarchal control

A key theme in Periyar’s Why Were Women Enslaved? Is his penetrating critique of the concept of Karpu (chastity), which he exposed as a culturally weaponised tool of patriarchal control. While the term can signify personal integrity, he shows how it has been historically applied only to women, reducing their moral worth to sexual purity. This, he argues, is a calculated patriarchal strategy to legitimise male dominance and institutionalise unequal standards of virtue.

Drawing from Hindu texts and traditions, Periyar deconstructs the Sanskrit idea of pativrata, loyal wifehood, and where pati denotes “master.”

Drawing from Hindu texts and traditions, Periyar deconstructs the Sanskrit idea of pativrata, loyal wifehood, and where pati denotes “master.” He critiques how religious narratives uphold a woman’s value through obedience, silence, and suffering, while men remain unbound by any equivalent moral expectations. His analysis is particularly compelling in how it links linguistic constructs to lived oppression.

What distinguishes Periyar’s argument here is his willingness to challenge not just religion and patriarchy, but also women’s own internalisation of these values. He contends that until women reject chastity as a divine or moral duty, true liberation is not possible. This section of the book is a bold confrontation of deeply entrenched cultural beliefs.

Marriage and masculinity: instruments of enslavement according to Periyar

Marriage, according to Periyar, is not just a personal union but a social institution that plays a central role in the subjugation of women. He condemns the ritualistic and Brahminical form of marriage because it binds women to their husbands through elaborate religious ceremonies. These rituals, in his view, glorify obedience and lifelong servitude. As a result, they strip women of the chance to realise their individuality and hinder the development of self-respect.

Moreover, he strongly critiques Hindu epics such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata for promoting idealised female figures like Sita and Draupadi. These characters, he argues, are revered not for their strength or agency, but for their suffering, obedience, and loyalty. Consequently, such narratives serve as a form of religious conditioning that justifies patriarchy. They reinforce the belief that a woman’s virtue lies in her endurance of pain and submissiveness to her husband.

One of the most radical elements of his feminist thought is his insistence that masculinity itself must be dismantled.

One of the most radical elements of his feminist thought is his insistence that masculinity itself must be dismantled. He maintains that no movement led by men, though it claims to advocate women’s rights, can result in genuine liberation. This is because male-led efforts are often rooted in the assumption of male superiority. For Periyar, true gender equality is only possible when masculinity is no longer equated with power, control, or rationality. Only then can men and women coexist on equal terms, free from the hierarchical structures imposed by gender roles.

Support for self-respect marriages and marital freedom by Periyar

In complete opposition to traditional Hindu marriages, Periyar introduced the concept of the Self-Respect Marriage, as part of the broader Self-Respect Movement. Although the book does not repeatedly name Self-respect marriage, its principles of rationalism, anti-caste resistance, and gender equality are present throughout.

For Periyar, marriage should not be a lifelong, unbreakable contract imposed by religious dogma or social pressure. Instead, he supports the concept of self-respect marriages, which are non-religious, consensual unions based on equality and mutual respect that allow for the dissolution of marriage if either party chooses.

The book advocates for the right to annul marriage and even the right to divorce, viewing it as essential to women’s liberation. He critiques traditional Hindu marriage rituals that bind women indefinitely, often trapping them in unhappy or abusive relationships. Annulment and divorce, in his view, restore individual freedom and dignity, preventing forced endurance of cruelty or neglect. This perspective challenges patriarchal norms that prioritise marital permanence over personal well-being, marking a radical departure from orthodox views. Through advocating this, Periyar empowers women to reclaim autonomy over their lives and bodies.

Property rights and widowhood: breaking material and social chains

Periyar was a powerful advocate for equal property rights for women, recognising that economic dependence is a key mechanism of control over women. He rejected the idea that women should be confined to stridhanam (gifts from marriage), which offered no real autonomy or security.

He even denounced the oppressive institutions of enforced widowhood as a tool of patriarchal and caste based control. He criticises the hypocrisy of social reformers who speak of women’s rights while upholding oppressive practices in their own lives. Highlighting the inhumanity of denying widows, even many of them children, the right to remarry, he argues that true social equality and freedom begin with liberating women from such bondage. Widow remarriage, for Periyar, is not just a reform but the first step toward dismantling systemic inequality.

In Why Were Women Enslaved?, he devotes a section to praising progressive policies (such as those in princely Mysore) that gave women the right to divorce, compensation, and property ownership primarily in cases where husbands were abusive or adulterous.

In Why Were Women Enslaved?, he devotes a section to praising progressive policies (such as those in princely Mysore) that gave women the right to divorce, compensation, and property ownership primarily in cases where husbands were abusive or adulterous. For Periyar, legal and economic independence were non-negotiable foundations for genuine liberation.

A vision beyond reform: towards liberation

Why Were Women Enslaved? is more than just a call for social reform; it’s a strong and clear statement advocating for women’s rights. In this book, Periyar questions the deep-rooted systems of patriarchy, caste, and traditional ideas about masculinity. Instead of asking for small changes or more representation within the existing system, he encourages a complete rethink of how society treats women.

The book intensively urges women to stand up against patriarchy. Periyar supported important ideas like women’s right to remarry, own property, and seek divorce, things that were uncommon at the time. He also introduced the idea of self-respect marriages and other progressive changes that aimed to give women greater freedom and equality.

Reference:

Ramasamy, E. V. (1942). Why were women enslaved? (M. Kandasamy, Trans.).

Sivasubramanian, S., & Joseph, A. V. (2018, March). Thanthai Periyar On Women and Development.

About the author(s)

Himani is a postgraduate in Political Science from Ramjas College, University of Delhi with a keen academic focus on gender, culture and social justice. Her academic and field experience includes research and project coordination in areas such as tribal entrepreneurship, environmental advocacy and community service.