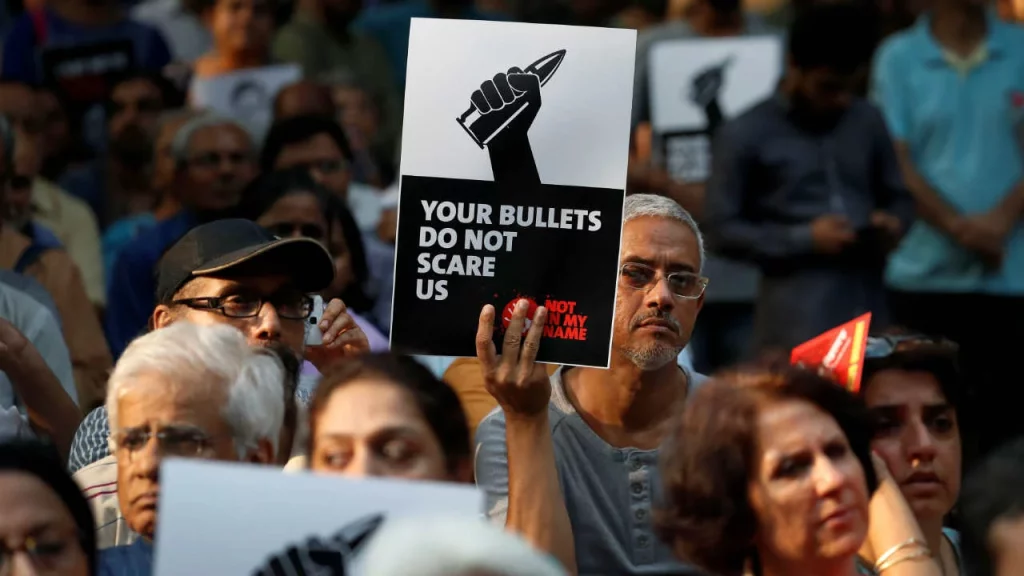

With 329 violations of free speech catalogued within the first quarter of 2025, marking acts of censorship, legal harassment, and homicide, democracy in India writhes under the blade of corruption. This assault on free speech continues unchecked in local courts, flouting established constitutional doctrine. Previously, the Supreme Court had established a common law principle for granting pre-trial interim injunctions. Injunctions are defined as provisional measures executed before trial, a court order to do or to not do something which may expose the plaintiff to injustice or harm. This principle is known as the Bonnard standard—in defamation cases, the courts should only issue an injunction when they are absolutely certain that the statement is false and cannot be justified—and was operative in the proceedings of the 2024 Bloomberg case.

The erosion of legal precedent: from Bloomberg to Adani

Zee, in its suit against Bloomberg and its journalists Anto Antony, Saikat Das and Preeti Singh who penned the article titled ‘India Regulator Uncovers $241 Million Accounting Issue at Zee,’ alleged that this article was composed of inaccurate details regarding the corporate and business operations of Zee, and had led to a 15% drop in share value, leading to substantial investor losses. It argued that this “false and factually incorrect” article was published with a premeditated and mala fide intention to defame the company. The article in question argued that the Securities and Exchange Board of India had found a gap of over $240 million in the accounts of Zee Entertainment Enterprises Ltd., which is more than 10 times more than was initially estimated by SEBI investigators.

The Adani case did not emerge in a vacuum. The willingness of courts to abandon constitutional principles in favour of corporate interests reflects a broader system pattern, reflected in the propaganda model pioneered by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent, which follows how money and power are able to direct the course of the printed news, marginalise dissent, and allow the reigning administration and prevalent corporations to transmogrify or quell voices conflicting with their interests.

The journalists in the case made the argument that Bloomberg, as a registered news organisation, embodies ethical reporting and factual accuracy, and that the article in question underwent thorough research and validation from trusted sources. The court, dismissing Zee’s appeal against Bloomberg, reiterated that such appeals were not considered maintainable unless grave urgency was demonstrated and underlined that such orders must be granted only when not granting them would cause “greater injustice” than granting them.

“In essence, the grant of a pre-trial injunction against the publication of an article may have severe ramifications on the right to freedom of speech of the author and the public’s right to know. An injunction, particularly ex parte, should not be granted without establishing that the content sought to be restricted is ‘malicious’ or ‘palpably false’. Granting interim injunctions, before the trial commences, in a cavalier manner results in the stifling of public debate. In other words, courts should not grant ex parte injunctions except in exceptional cases where the defence advanced by the respondent would undoubtedly fail at trial,” the top court had said in the Bloomberg case. In light of this case, the Supreme Court expressed concern about courts recognising “Strategic Litigation against Public Participation” suits across jurisdictions. ‘We must be cognisant of the realities of prolonged trials… While granting ad interim injunctions in defamation suits, the potential of using prolonged litigation to prevent free speech and public participation must also be kept in mind by courts,’ the Bench had cautioned in the verdict in the Bloomberg case.

The Adani injunctions: a case study in media suppression

On the 6th of September, a Delhi court acquiesced to the demands of industry conglomerate Adani Enterprises and ordered an injunction against nine journalists and digital platforms from the publication and distribution of content Adani deemed “unverified and defamatory”. The accused journalists and content creators span some of the nation’s most forthcoming vocal voices, such as Ravish Kumar, Dhruv Rathee, Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Abhisar Sharma. The court ordered an immediate removal of media content, including nearly 140 YouTube videos and over 80 Instagram posts from prominent news outlets and commentators. This was enforced by India’s Information and Broadcasting Ministry (MIB) through rapid takedown notices. The Adani Group alleged in its litigation that the reporting by Newslaundry was ‘ill-motivated and untrue and had inflicted untarnishable damage to the reputation of the group.’ However, none of the allegedly defamatory content was examined in court.

In light of Bloomberg case, the Supreme Court had expressed concerns, ‘We must be cognisant of the realities of prolonged trials… While granting ad interim injunctions in defamation suits, the potential of using prolonged litigation to prevent free speech and public participation must also be kept in mind by courts.’

On Thursday, September 18, a district court set aside the September 6 order following a challenge by four journalists, Ravi Nair, Abir Dasgupta, Ayaskanta Das and Ayush Joshi. Another district judge, hearing a separate appeal filed by Guha Thakurta, has now posted the matter to September 22. Following the ruling, Newslaundry and Ravish Kumar had also challenged the September 6 gag order, but district judge Sunil Chaudhary had adjourned Newslaundry’s petition for October 15.

The court ordered ‘prior restraint’ on Guha Thakurta and the other journalists, preventing publication and distribution of any “unverified, unsubstantiated and ex facie defamatory reports” about AEL before a court trial can determine whether the content actually is of a defamatory nature. This is an unconstitutional restriction on the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution. Restrictions on free speech under Article 19(2) involve interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation, and incitement to an offence. Legislations imposing prior restraints on free speech face the imperative to prove that the reason for this restraint is justified under Article 19(2).

The gag order over reporting on AEL for Paranjoy Thakurta was lifted, with the district court noticing the absence of reasoned findings and expressing concerns about imposing reporting restraints without such mandatory information. Additionally, the Delhi High Court ordered a status quo on removing content of AEL from Newslaundry, stating that it will not be demanding the removal of any more content from their sites or any other intermediary, but that the previously erased content could also not be uploaded once more.

Manufacturing consent: the propaganda model in action

The Adani case did not emerge in a vacuum. The willingness of courts to abandon constitutional principles in favour of corporate interests reflects a broader system pattern, reflected in the propaganda model pioneered by Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky in Manufacturing Consent, which follows how money and power are able to direct the course of the printed news, marginalise dissent, and allow the reigning administration and prevalent corporations to transmogrify or quell voices conflicting with their interests. The essential ingredients of this propaganda model, or set of news “filters”, fall under the following headings: (1) the size, concentrated ownership, owner wealth, and profit orientation of the dominant mass-media firms; (2) advertising as the primary income source of the mass media; (3) the reliance of the media on information provided by government, business, and “experts” funded and approved by these primary sources and agents of power; (4) “flak” as a means of disciplining the media; and (5) “anticommunism” as a national religion and control mechanism. These elements interact with and reinforce one another.

In the digital age, this flak has evolved into sophisticated legal warfare, employing the very institutions meant to protect democratic freedoms as weapons against those who dare to speak truth to power. The Adani case exemplifies this modern flak in its most pernicious form. By weaponising defamation laws and exploiting judicial processes, corporations can now effectively silence criticism without ever proving their case in court.

Of particular interest to us is the fourth filter—“flak,” referring to negative responses to a media statement or programme, which could take the form of letters, telegrams, phone calls, lawsuits, or other forms of complaint and attack. In the digital age, this flak has evolved into sophisticated legal warfare, employing the very institutions meant to protect democratic freedoms as weapons against those who dare to speak truth to power. The Adani case exemplifies this modern flak in its most pernicious form. By weaponising defamation laws and exploiting judicial processes, corporations can now effectively silence criticism without ever proving their case in court. The mere threat of legal action, combined with compliant courts willing to issue blanket injunctions, creates a chilling effect that extends far beyond the immediate targets—journalists hesitate to publish material that flies in the face of the ruling party in fear of legal annihilation, and governments find they no longer need to face the consequences of overt censorship; they can simply allege defamation and emerge unscathed.

The Adani injunctions represent more than an attack on specific journalists; they constitute an assault on the very foundations of democratic discourse. When courts abandon established legal principles like the Bonnard standard and legal precedent in favour of corporate interests, the machinery of justice transforms into an instrument of oppression, and democracy itself hangs in the balance.