When the peaceful valley of Kashmir was rocked by protests in 2016 in response to the killing of Burhan Wani, in a collective expression of freedom, thousands of young men were injured or blinded after they became targets of indiscriminate firing by the army. However, one of the most overpowering scenes of the conflict was the presence of women at the forefront, who marched in a colorful protest, shouting, “Hum kya chahte? Azadi” (What do we want? Freedom). Ever since independence, Kashmiri women have been at the forefront of resistance in both active and passive ways—whether by providing refuge to their men and armed fighters, hiding weapons, passing on messages, singing songs glorifying martyrs, and preserving memories. Women have braved socio-economic and health fallouts of the conflict to change and fit into gender roles within their societies, moving from dependents to bread earners, from followers to leaders within families. Yet, for them, resistance has come at a cost – their bodies turning into sites of conflict through an attack on the ‘honor’ of the community. Mass rapes and mutilations are very often the price women pay for resisting whenener a conflict arises whether it’s Manipur or Kashmir.

Yet, the struggle of Kashmiri women is a singular strand amongst the struggles faced by social and political activists in attempting to reclaim their voices. While discussing activism, it is crucial to mention the gendered burden it carries, clearly blurring the boundaries that ultimately decide who gets to protest. For many socio-political activists, resistance is a privilege. From the Dalit movement in India to the queer movement for recognition, from the struggle of women in Kashmir and Manipur to the everyday struggles faced at micro-levels, activism isn’t free from the patriarchal structures that it actively seeks to dismiss. Like any other form of social participation, it is influenced by social dynamics and the inequalities of caste, class, religion, and sexuality. Similarly, the invisible networks of labour—emotional, logistical, and physical—are deemed too insignificant to be brought to discussion by academicians, with rarely any studies devoted to analysing the gendered nature of activism.

Gendered protests: the hidden costs of activism

“Women have always been involved in protests in places like India, Bangladesh and Pakistan but the difference is that they’re taking on more leadership roles and are the primary actors,” Heather Barr, associate director of Human Rights Watch’s women’s rights division, told CNN. Yet, on a repeated basis, they are prone to threats of harassment, including targeted intimidation, physical threats, online abuse, surveillance and legal threats by the state. Additionally, they also face challenges from the anti-rights movements in terms of their physical safety.

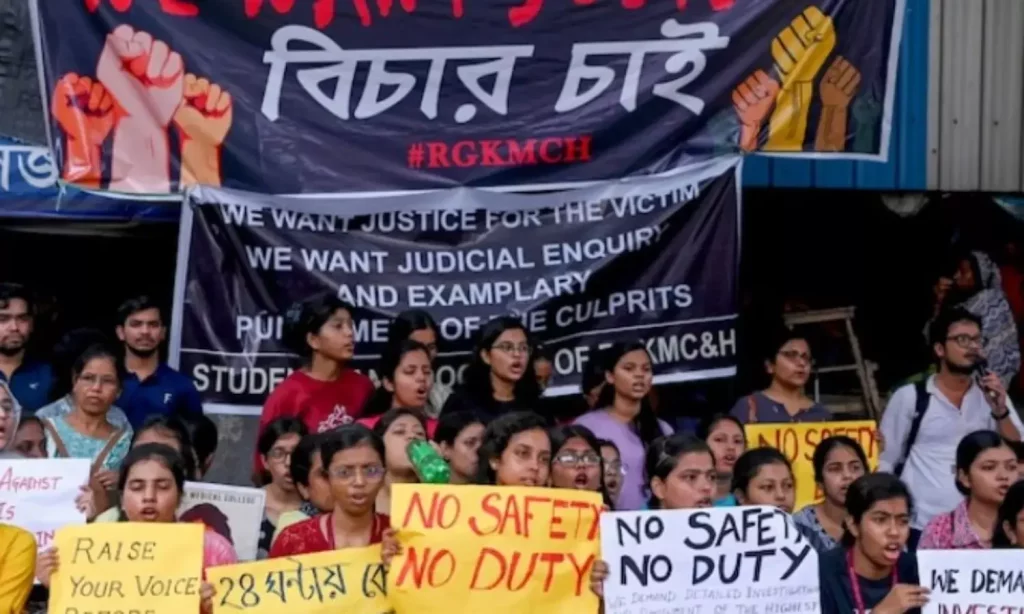

Meghmala Ghosh, who went on a protest after the rape and murder of a trainee doctor in a medical college of West Bengal in August last year to “reclaim the night”, underscored how staying out late poses a key challenge. “As soon as it was 12, I felt ‘It’s getting too late”, Ghosh said, as Esha Mitra reported for CNN. Nazifa Jannat, a political activist in Bangladesh, echoes similar sentiments. “When you’re walking on the road you constantly feel eyes on you, whether it’s a busy market or a deserted road,” she said.

For many socio-political activists, resistance is a privilege. From the Dalit movement in India to the queer movement for recognition, from the struggle of women in Kashmir and Manipur to the everyday struggles faced at micro-levels, activism isn’t free from the patriarchal structures that it actively seeks to dismiss. Like any other form of social participation, it is influenced by social dynamics and the inequalities of caste, class, religion, and sexuality.

Intimidation tactics targeting families are also often used to scare away women, with a primary challenge coming from the underlying thought “Ghar-baar chodkar protest karne baithi hain” (They are sitting on a protest after leaving their homes). Khadija Shah, a prominent political activist who was involved in the protests against the arrest of Pakistan’s former PM Imran Khan following charges of corruption, noted that, “Like many other parts of South Asia, access to political spaces is further limited by whether you belong to a privileged caste or class in society. My photo was shared everywhere; there were people calling for my rape by the police and saying I should be skinned alive.”

While analysing the gendered burden of activism, the disproportionate burden very often falls upon women who carry burdens and have responsibility to their own family and community as caregivers. Data underscores this imbalance. As per a time-data survey of the ORF, women, on average, spend 335 minutes per day on domestic work as compared to 40 minutes by men. Time poverty directly impacts the chance and the opportunity to protest, leaving them with far less discretionary time to travel and remain at protest sites. Similarly, an average devotion of 43-47% of waking hours on unpaid caregiving work as compared to 5-10% for men means women bear the unequal brunt of domestic work in India. This makes protest participation a higher economic and political gamble for them. In states with extreme gendered time ratios (Haryana, Punjab, Gujarat), cultural norms likely limit women’s participation and mobility outside home. Dalit, lower-caste and queer women are more prone to constraints – where time poverty intersects with stigma to perpetuate greater invisibilisation. The invisible caregiving burden is a hidden barrier, showing that redistributing care is a structural lever, and socialising care would mean more women would be able to participate actively without sacrificing either.

The gendered aspect of protest culture

Reproduction of female labour is the driving pulley in most households. In more recent times, one of the most significant aspects of the anti-CAA protests that brought attention to Shaheen Bagh – a small Muslim-dominated area of South Delhi – was the participation of elderly women, mostly aged between 70 and 80 years, as they held the constitution in one hand and the Quran in the other to assert their equal right to their homeland, even making it to Time magazine. Yet, the shrinking space for civil society meant they faced threats of legal consequences from the state, with physical repression tactics used to manufacture fear.

Yet, for women, resistance has come at a cost – their bodies turning into sites of conflict. Mass rapes and mutilations are very often the price women pay for resisting whenener a conflict arises whether it’s Manipur or Kashmir.

In 2018 and 2019, more than 10,000 male farmers committed suicide each year, according to a 2019 report by the National Crime Records Bureau. Although female farmers represent 75 per cent of the female working class in rural areas of India, they own barely 13% of the farmland. According to the India Human Development Survey, 83 percent of agricultural land is inherited by male members of the family and less than 2 percent by females. Spousal deaths coupled with the inability to access subsidies, care, food and shelter following the three farm laws calling for deregulation of an already shaky market meant that women, in large numbers, took to protest sites. Yet, the protest wasn’t without challenges. They face persecution, repression and arrest. In one prominent incident, Disha Ravi, a 22-year-old climate activist, was arrested in the southern city of Bengaluru on February 13 on the charge of sedition for publishing and disseminating an online toolkit of nonviolent tactics to support the protesting farmers.

Political power silencing the protesters

Similarly, the silencing of sexual abuse allegations against Brij Bhushan Singh, the former president of the Wrestlers’ Federation of India and former BJP MP, shows how power and influence intersect to perpetuate discrimination and inequality. He faced several allegations by female athletes, such as unwanted touching, soliciting sexual favours and assaulting several girls and women. Vinesh Phogat and Sakshi Malik were just two of the voices which faced great harassment, abuse and intimidation for participation by the police and the government alike.

In a conversation with Feminism In India, Ameena Ashraf (name changed for protection of identity), a final-year student of Lady Shri Ram College for Women, who was a part of the stall selling keffiyeh and souvenirs of a Palestinian identity set up at the annual Diwali Mela and is a leading voice for the freedom of Palestine, highlighted the challenges of activism. “It wasn’t easy; we faced administrative tussles, with our work being excessively scrutinised. However, the overwhelming response from the students and faculty alike was worth it,” she said. Campus dissent and the silencing of voices today pose a significant hurdle for student activists seeking change, with administrative delays, refusal to grant permission, and surveillance constituting risks.

From Kashmir and Shaheen Bagh to the anti-farm bill protests and Manipur protests, women have been at the forefront of resistance, co-creating spaces of mobility, activism and better representation. Yet, the structural flaws that limit the chances to protest turn activism into a contentious space, where opportunity and privilege determine who gets to protest and become part of the change.

From Kashmir and Shaheen Bagh to the anti-farm bill protests and Manipur protests, women have been at the forefront of resistance, co-creating spaces of mobility, activism and better representation. Yet, the structural flaws that limit the chances to protest turn activism into a contentious space, where opportunity and privilege determine who gets to protest and become part of the change. Recognition of emotional labour, intersectional solidarity, and redistribution of caregiving responsibilities are immediate solutions. In the long run, a positive transfer of power by restructuring social relations is vital to address the challenges posed by the gendered burden of activism. Unless activism is free from the very structures that constrain it, reform will be a distant dream.

About the author(s)

Nausheen is currently an undergraduate student pursuing journalism at Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Delhi University. With a keen interest in feminism, geopolitics, and social issues, her passions lie in research, writing, and public speaking. In her free time, she enjoys listening to music, sipping coffee, and playing chess.