When iconic and loveable anti-heroine Phoebe Waller-Bridge (aka Fleabag) exclaimed, ‘Hair is everything!’, this quote struck a chord with millions of sympathetic viewers across the globe. Fleabag, however, did not anticipate how right she truly was—in an intersectional society, from scalp-shaving as a form of social protest to being an offshoot of systemic discrimination, hair, too, is inherently political.

The Body as a Site of Power

A conversation on the politics of the body cannot truly begun without an honorary mention of Michel Foucault. Foucault examines the body as a target of power to form the basis of his argument: a docile body is to be subjected, transformed, used, and improved, implying a new scale of control. This new modality of control revolves around never-ending, continuous coercion, which is exercised with respect to a codification that partitions time and space. In Foucault’s theories, modern power is a nexus of non-centralised forces, an interplay of dominance and subordination, and is maintained, not through physical restraint and coercion, but through individualised self-surveillance and self-correction to reinforce norms. As Foucault writes,

‘There is no need for arms, physical violence, or material constraints. Just a gaze. An inspecting gaze, a gaze which each individual under its weight will end by interiorising to the point that he is his own overseer, each individual thus exercising this surveillance over and against himself.’

This theoretical framework becomes viscerally tangible when applied to the politics of hair—particularly women’s hair. Andrea Dworkin articulates this reality with unflinching clarity, stating, ‘In our culture, not one part of a woman’s body is left untouched, unaltered. No feature or extremity is spared the art, or pain, of improvement…. From head to toe, every feature of a woman’s face, every section of her body, is subject to modification and alteration. This alteration is an ongoing, repetitive process. It is vital to the economy, the major substance of male-female differentiation, and the most immediate physical and psychological reality of being a woman. From the age of 11 or 12 until she dies, a woman will spend a large part of her time, money, and energy on binding, plucking, painting, and deodorising herself. It is commonly and wrongly said that male transvestites, through the use of makeup and costuming, caricature the women they would become, but any real knowledge of the romantic ethos makes clear that these men have penetrated to the core experience of being a woman, a romanticised construct.’

The Illusion of Choice

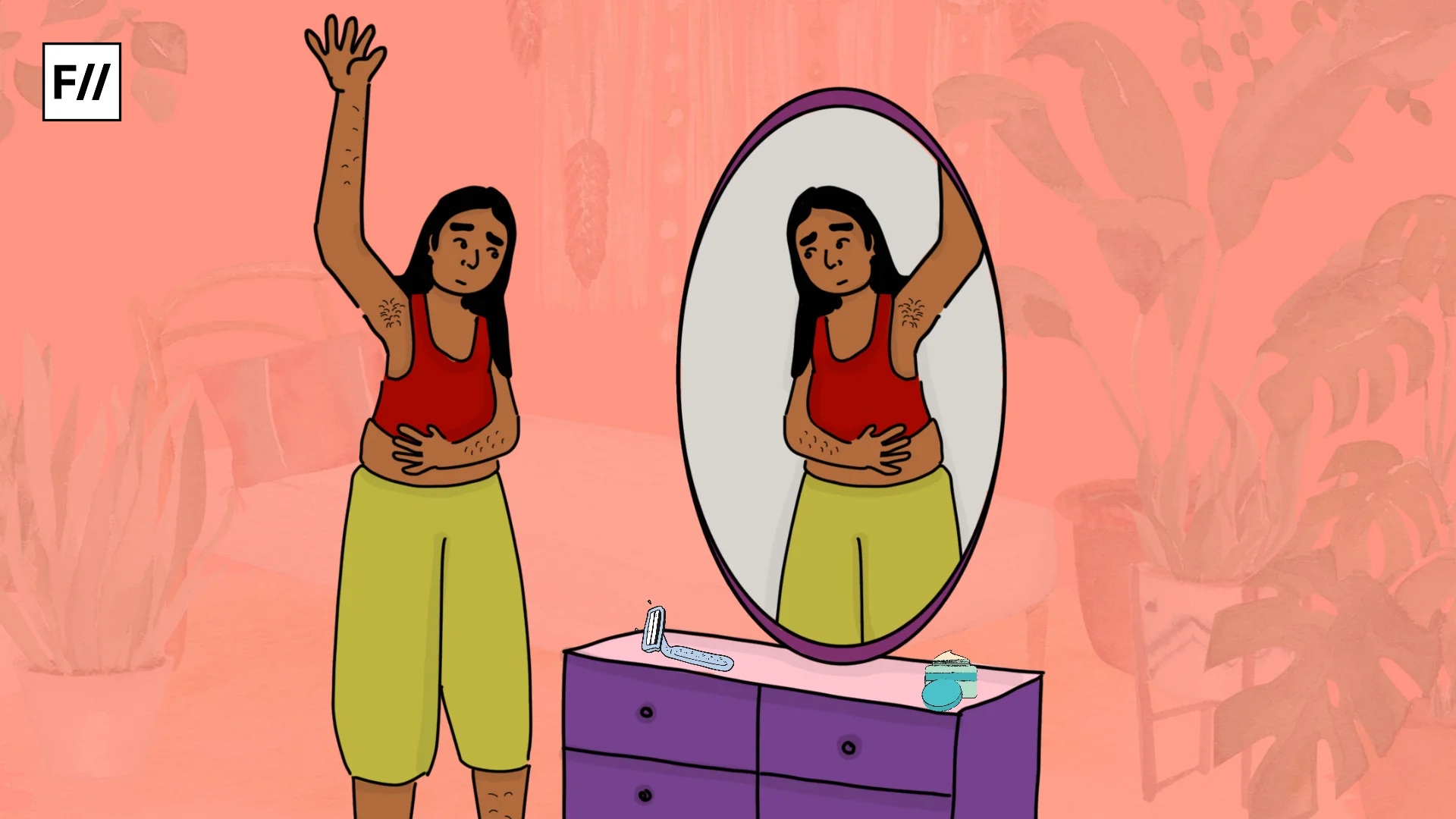

This echoes the postmodern beauty standard of hairlessness, systematically quelling bodily autonomy and freedom and parading this oppression as an individual choice. Influential corporations with hefty pockets have invested substantially in repackaging women’s hair removal as female empowerment, reinforcing the aesthetic norm and de-normalising natural characteristics of the body. As Susan Bordo writes in ‘Foucault, Feminism and the Politics of the Body‘, ‘Normalisation, to be sure, is continually mystified and effaced in our culture by the rhetoric of “choice” and ‘self-determination’ which plays such a key role in commercial representations of diet, exercise, hair and eye colouring and so forth.’

Regardless of what a woman’s self-determined hair choice is—whether to veil, unveil, shave, grow, colour, or cover—society ordains that it will be surveilled, monitored, and enforced. Hair becomes not merely a personal aesthetic decision but a battleground where patriarchal, religious, and commercial forces converge to exert control over women’s bodies.

Hair as a Religious and Political Weapon

Hair has historically been a deeply political site, being a chassis of modesty, sexuality, and womanhood, with Bengali Hindu widows being forced to shave their heads as a symbol of permanent humiliation, branding them as desexed, dehumanised widows for the rest of their lives.

Hair has historically been a deeply political site, being a chassis of modesty, sexuality, and womanhood, with Bengali Hindu widows being forced to shave their heads as a symbol of permanent humiliation, branding them as desexed, dehumanised widows for the rest of their lives.

India itself has been seeing rampant polarisation and religious discrimination, with the state of Karnataka facing an outcry in 2022 when one of their colleges barred several Muslim women for attending their classes wearing a hijab. This mandatory unveiling is also a feature of a Hindutva-led tyrannical state, in which pure contempt and distaste towards minority religions manifests itself in forcible acts of religious disrespect. After Nitish Kumar, current CM of Bihar, pulled down Nusrat Parveen’s hijab during a government function, Aakar Patel, Chair of the Board at Amnesty International India, said, ‘Such actions deepen fear, normalize discrimination, and erode the very foundations of equality and freedom of religion. This violation demands unequivocal condemnation and accountability. Urgent steps must be taken to ensure that no woman is subjected to such degrading treatment.’ Regardless of what a woman’s self-determined hair choice is, society ordains that it will be surveilled, monitored, and enforced.

This phenomenon of the politics of hair even extends into spheres of caste and class, as 250 Dalits residing in the Banaskantha district of Gujarat were firmly refused barbershop services, forcing them to conceal their castes and travel to other villages for grooming services.

These acts are not conducted in isolation but are indicative of a broader trend within a fascist nation of inflicting bodily humiliation to marginalise minorities and reinforce hegemonic power.

Hair as Resistance

Yet hair can also become a powerful tool of resistance, a symbolic weapon wielded by the oppressed to demand visibility and justice. Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs), who have historically been saddled with inadequate remuneration and poor working conditions despite their critical roles of providing primary care to lakhs of Indians, were protesting their prevailing compensation structures in front of the government Secretariat in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. Fifty days through this agitation, on the 31st of March in 2025, they lent greater visibility to their fight by chopping off their hair, screaming out their slogans and waving their newly detached hair as a form of disappointment and contempt for the state’s lack of receptivity to their struggles. The act of self-inflicted hair removal inverts the typical oppressive cycle, with women regaining control over their own appearance and liberating themselves from the traditional mechanisms of control.

Hair as a form of social protest may be exemplified in the movement of thousands of Iranians against the mullah regime. In 2022, 22-year-old Mahsa Amini died in custody of the morality police during her detention for flouting the mandatory hijab laws—by having a lock of hair not properly hidden in the scarf. Iranian women began shearing off their locks as solidarity with their sister lost to the hegemonic fascism of the state and as a display of grief and mourning. According to Iranian sociologist Chahla Chafiq, the gesture of women demonstrators with mutilated hair is an expression of collective mourning.

In a paradigm of rampant commodification of the female form, commercial manipulation, patriarchal surveillance, caste-based discrimination, and ethno-religious domination, hair remains a contested terrain where power, identity, and resistance collide. Hair is political—whether it is a site of oppression or a dramatic gesture of resistance.

Reference:

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/kerala/kerala-asha-workers-make-emotional-statement-cut-hair-in-protest-against-government-apathy/article69395776.ece

https://www.theswaddle.com/the-shame-and-scandal-of-indian-womens-hair-follicles

http://ieas-szeged.hu/downtherabbithole/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Bordo.-Foucault-Feminism.pdf

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/12/india-chief-ministers-removal-of-womans-hijab-demands-unequivocal-condemnation/

https://thelogicalindian.com/after-80-years-250-dalits-in-gujarat-village-finally-access-local-barber-services-ending-caste-discrimination/#:~:text=Historic Cut in Gujarat’s Banaskantha,of Exclusion and Emerging Change

https://www.dailyo.in/news/why-are-women-in-iran-taking-off-hijabs-cutting-their-hair-37357

https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/views/news/hair-humiliation-and-madness-policing-bodies-4000266