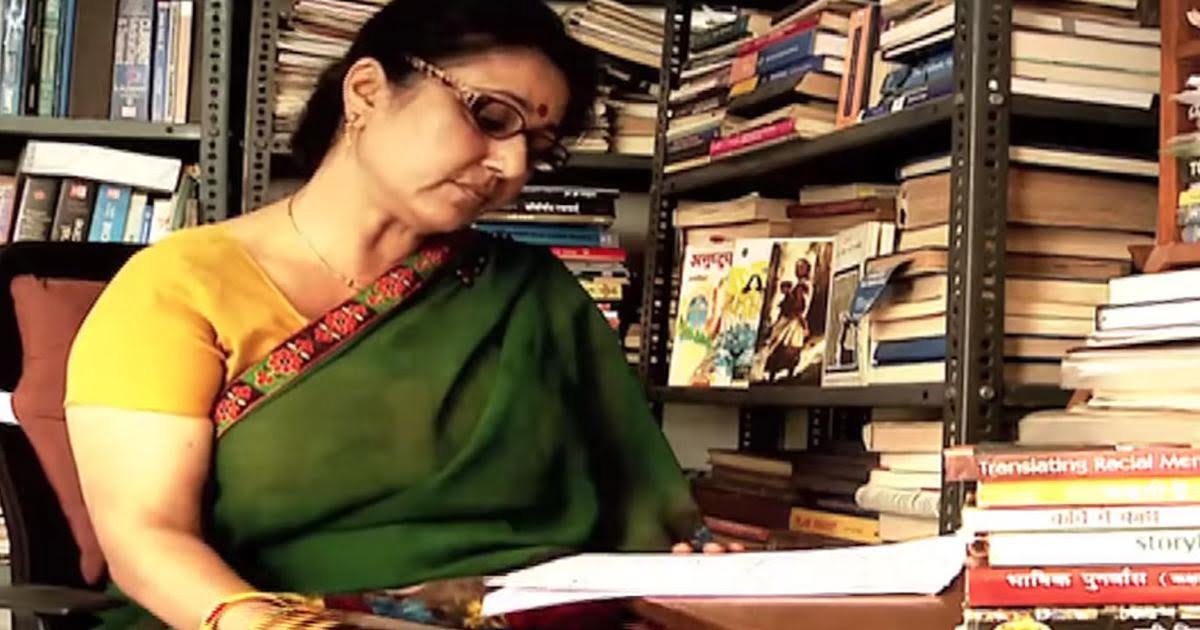

Anamika is a poet, writer, critic (literary and social), who has been honored with many awards including the 2020 Sahitya Akademi Hindi poetry award. She is the author of eight collections of poetry, which include Anushtup, Doob-dhaan, Khurdari Hatheliyaan, Tokri mein Digant, and Paani ko Sab Yaad thaa. Tokri mein Digant is the collection of poetry for which she has been given the Sahitya Akademi puraskar. Her poems have been translated into English in a collection titled My Typewriter is My Piano. Her oeuvre has consisted of many creative engagements with feminist issues and the force of her creative and poetic vision is well-known and respected in the Hindi literary world. Currently, among other creative engagements, she also teaches English Literature at a college in the University of Delhi.

The sixty-five-year itch…

In a case of rare March madness, this year, the Indian academy of letters, Sahitya Akademi conferred its yearly prize for poetry in Hindi to the eminent Hindi poetess Anamika. Why is it rare you ask – because in the award’s sixty-five-year history, the award for Hindi poetry has never been given to a woman poet; leave alone to a fiercely iconoclastic and feminist poet like Anamika. (for context: in one of her poems, she ruminates about how Christ could have carried on the burden of Godhood had he suffered from the masik dharma or the menstrual cycle! Or how he could possibly have wandered in the wilderness if he was besieged by the fear of sexual predators like women everywhere across time and space have been.)

In a case of rare March madness, this year, the Indian academy of letters, Sahitya Akademi conferred its yearly prize for poetry in Hindi to the eminent Hindi poetess Anamika. Why is it rare you ask – because in the award’s sixty-five-year history, the award for Hindi poetry has never been given to a woman poet; leave alone to a fiercely iconoclastic and feminist poet like Anamika.

To truly understand why this decision should be celebrated as a harbinger of better times for feminist writing, one has to see it through the eyes of the literary canon and women writers, who have been—through their shared history—to put it mildly, star-crossed lovers.

The literary canon has traditionally contained the most respected and the most representative texts of any culture. It is the collection of all literary works which are considered the best and most revered in any culture. The formation of a literary canon, standardisations of languages (like Hindi or Urdu) and the rise of a national consciousness and identity usually go hand in hand in most countries. Needless to say, in most cases, all three of these tendencies have been patriarchal and masculine in nature. The Indian nationalisation in the 19th century saw a meteoric rise in the proliferation and ‘discussion’ of the ‘woman’ question. This included sub-questions like: what can women do to contribute to the national struggle? What is the correct level of exposure for them? How much modernity can be allowed to them? Would their role change in the ‘modern’ and ‘democratic’ country which Indians were fantasizing about before 1947? Etc..etc…etc…

The one and only – Bharat Mata

Most pre-independence male writers and reformers decided that the creation of a national identity was more important and all other questions, including the ‘religion question’, ‘language question’, the ‘woman question’, the ‘Dalit question’ and others became sub-sets of the one pressing matter of a composite Indian identity. Women were given the satisfaction of being represented metaphorically in the image of Bharat Mata – the country was now an ideal woman and this was the ideal that women were to emulate. All other versions of womanhood were deferred. Independence became a thing of the present and then a thing of the past but the ‘question(s)’ of women remained.

Also read: Bharat Mata Iconography: Nationalist Imaginations Of Femininity & The Female Body

After a pregnant and expectant lull in the women’s movement in post-independence India, women writers picked up their banners and pens again in the 70s and 80s. Writers like Anamika, active and influential since the 1990s have inherited the frustrations of the slow change in the representative and lived lives of women decades after independence.

Along with writers like Nirmala Garg, Katyayani, Savita Singh and Neelesh Raghuvanshi. Anamika has attacked the stalemate condition of the feminine consciousness which is justified through cultural abstractions like cultural, religious and literary traditions. Anamika, along with these other writers are no strangers to institutional recognition as their work has been acknowledged in most modern histories of Hindi literature.

To be or not to be – in the canon

Despite the institutional acknowledgment, women writers and their subjects have still been considered a ‘niche’ rather than a fundamental and ‘pan-social’ concern. In the sixty-five years since the institution of the Sahitya Award, legendary women writers like Krishna Sobti have been honored for their prose work but poetry has strictly been male-dominated. It is needless to say that this oversight has not been due to a dearth of capable writing by female poets (or even feminist poets, for that matter). The institutional recognition of the work that poets like Anamika have been doing since the last forty odd years in bringing women’s writing, feminist writing, women’s modern poetry and women’s life writing into the folds of mainstream acceptability has clearly been insufficient till now. While praise has been ample, the official recognition has been cautious. As she writes in her poem ‘Talashi’

They said, “Hands up”

They broke up each part of me,

to search me

Whatever did they find through my search?

some dreams they found and found a moon

A packet full of cigarettes

A matchbox full of hope, A half-written letter

which they could not decode

that’s because it was the time of the Indus Valley civilization

when I wrote it

in an impenetrable script

addressed to my earth

“Hello Earth, let’s go away somewhere together earth

How long will we both rotate, each on our axis like plodders

come, lets stare askance somewhere else

become fire-tailed meteors

far from this well-trodden orbit…”

They twisted the letter

and locked me into the dungeon

unceasingly with my pen,

I have been digging since then

A tunnel out of my allocated dungeon…

[emphasis and translation mine]

This is the image of a woman, who has used language (perhaps poetic) to write a personal letter to her ‘own’ piece of earth, in a language that no one understands. the image of the meteor or the ‘Agnibaan’ in Hindi also evokes the cultural memories of the arrow of fire with which Ravan was killed and so also brings alive the character of Sita, who was born of the earth.

So the image becomes multilayered with the ‘daughter’ Sita writing a letter to her ‘mother’ earth and then trying to furrow out of her dungeon through the earth. The poem talks of the metaphoric state of women writers, as well as all women, who speak of their lives in tongues and dialects that men (‘they’) have never understood; women who crave for their patch of green, grass-laden meadow and who have been captured in symbolic dungeons after being searched for any signs of digression and transgression. What is the crime of this woman in Anamika’s poem? One doesn’t know. Being assigned corners and closed spaces, without any explanation except the well-trodden path and explanation of, “this is how it has always been” is an experience most women will be familiar with. With Anamika’s poetry, these mundane experiences can transcend banality and become poetic.

The Sahitya Akademi award is a symbolic acceptance of the women’s experiences, ordinary as well as extra-ordinary, expressed in poignant and vibrant verse, into the canon of acceptable subject for the high art of poetry. Women’s writing has always been a merging of the political and the personal. Thousands of women have fought long and arduous battles for the legitimisation of the female personal as a valid landscape for the evocation and canvassing of the poetic. Literary developments like this award give women writers the space to save themselves from becoming more ‘man’ than men. Since poetry has always been the primary cultural and literary index, this inclusion of poetry, of women, by a woman, and for all women, is an important historical moment.

Being assigned corners and closed spaces, without any explanation except the well-trodden path and explanation of, “this is how it has always been” is an experience most women will be familiar with. With Anamika’s poetry, these mundane experiences can transcend banality and become poetic.

Some feminist activists and theoreticians can reject the desirability and validity of the canon on grounds of it being a patriarchal representation and domain. The important questions in this debate are many. Do we accept one high canon? If so, do we reject the traditional ONE canon? Do we desire the inclusion of women into the high canon? Or do we change the conceptualization of the canon as a continuously changing entity and hence accept that it has finally now opened its arms to many who have till now been fighting their battles from the margins?

Also read: Subhadra Kumari Chauhan: Poet, Social Reformer And Freedom Fighter | #IndianWomenInHistory

One way or another, this announcement and award have changed the playing field and opened the way for many other women writers to hope for the scope of reach and influence that institutional recognition and inclusion can provide to their long-drawn out literary struggles.

Tarika is an avid thinker, occasional writer, and an impulsive feminist but mostly spends her days teaching English literaure at a college in DU. She can be found LinkedIn and Facebook.

Featured image source: Scroll.in