My love for retro Hindi cinema music often becomes a motivation for me to revisit the early days of Hindi cinema, when both, the Indian nation and the captivating mass medium of cinema were in the making. Hindi cinema, which has now attained a pan-Indian and an almost global reach under the commercialised banner of Bollywood has indeed had a long journey, devoted to reflecting the socio-cultural ethos of what is now the Indian nation, while also being invested with the task of tailoring and disciplining what could be viewed as a reflection of a society, of a nation in the making.

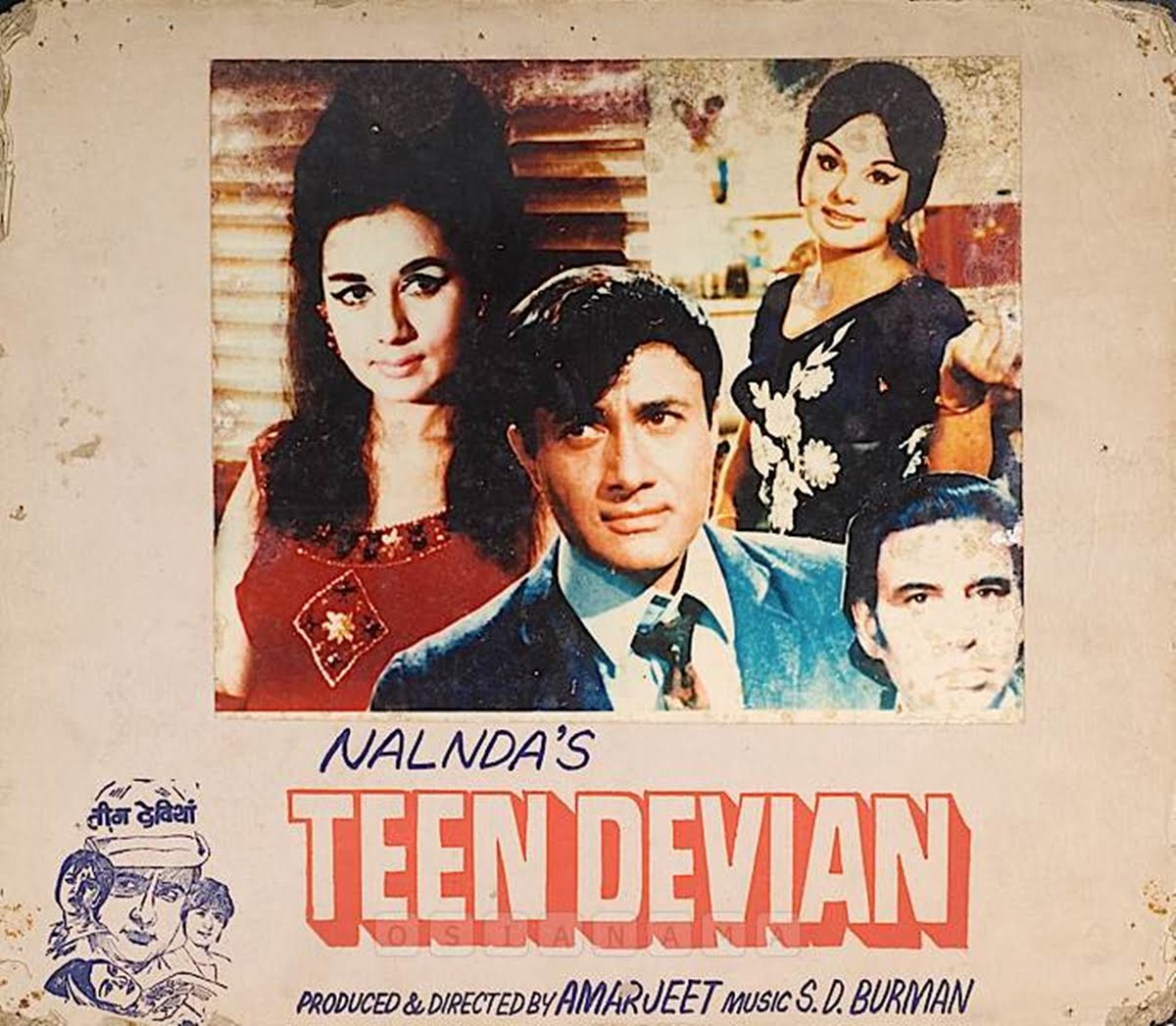

While it may be argued that Hindi cinema has indeed progressed in its content from those in the ‘50s through the ‘70s to a more responsible portrayals of the society, most of the recent content depicted through Hindi cinema, disseminating in the commercial sphere, catering to a large viewership has arguably progressed very little. While dissecting the present condition of Hindi cinema is beyond the analytical scope of this essay, I aim to underscore how Hindi cinema in the early years of nation-building was not only a medium to abet this project, but was an apparatus of disciplining the nation and entrenching the gender roles, the image of the ‘Indian’ woman through a disciplining male gaze. I have analysed the film Teen Devian (1965, directed by Amarjeet) in this regard, which was a box-office hit, generating a large viewership, primarily due to the legendary actor Dev Anand.

The beautiful track, Khwab ho tum ya koi haqeeqat, sung by Kishore Kumar and composed by S.D Burman from the album led me to revisit this film, the lines which run through the entire length and breadth of the run time of the film, as the male protagonist embarks on a journey of love.

Also read: Anaahat (2003): Niyog Pratha & Women’s Sexual Freedom In Amol Palekar’s Film

The plot of the film is, at the surface-level, simple, like most of the films during that period of narrative cinema. Set in an urban setting, in the city of Calcutta, an aspiring poet, Dev Dutt (Dev Anand) works at a music shop and encounters three women, played by Nanda, Kalpana and Simi, initially at different points in time and gradually starts associating (romantically) with all of them simultaneously. He is then faced with the dilemma of who among them he should take as his life partner and eventually realises his love for Nanda. This indeed simple tale is problematic on various levels.

Teen Devian, which depicts three women as central characters is seen and shown through the eyes of the male protagonist, whose voice is paramount, the only voice controlling the narrative. The portrayal of women in the early years of Hindi cinema has been peripheral, “restricted to saree-clad romanticism in the woods, upholding of Indian values in the households, abduction, vulnerability and excessive protectorship from her male counterpart”.

Teen Devian, which depicts three women as central characters is seen and shown through the eyes of the male protagonist, whose voice is paramount, the only voice controlling the narrative. The portrayal of women in the early years of Hindi cinema has been peripheral, “restricted to saree-clad romanticism in the woods, upholding of Indian values in the households, abduction, vulnerability and excessive protectorship from her male counterpart”.

These images of women contained in the peripheries of an essentially male world formed the crux of Hindi cinema during that period, creating an image of the ‘Indian’ woman wherein women are symbolically akin to nature or the softer Indian nation while the men drive the material-cultural Indian nation-state.

Teen Devian, through a romantic storyline, ascertains and legitimises the gendered way of seeing the ‘Indian’ woman. Brief descriptions of each female character must be given in order to move further in the discussion. Dev first gets romantically involved with Nanda, a woman hailing from a village, working as a typewriter in the city. Nanda, is a perfect blend of rural values and urban self-sufficiency. The second female character who gets attracted to Dev and subtly returns the affection, is Kalpana, who is an actress. The third Devi is Simi, a socialite, who is initially in love with Dev’s poetry and gradually falls in love with the poet himself.

Throughout the film, male infidelity is casually and romantically portrayed as Dev pursues all three women at the same time and the viewers are engaged in a narrative to evoke empathy for Dev in the dilemma he is faced with to choose the right Devi for himself and are invited to partake in the pleasure of looking at the three women through the man’s gaze, through a rather humorous undertone.

While Dev would not leave a single opportunity to involve himself with the two other women, Nanda would relentlessly and uncomplainingly take care of him. The identification of the three women through Dev’s eyes reaches a problematic climax when Dev, through playing three imaginary scenarios in his head of how his marital life would be depending on whom he marries, chooses Nanda.

In the first scenario, when he imagines being married to Kalpana, the image of a highly ambitious actress who places her work above her husband is depicted. In the second scenario, he imagines being married to Simi, wherein she is depicted as a body-conscious socialite who places her image before pregnancy and her husband. In the final scenario, he imagines Nanda as his wife, who is depicted as an ever-forgiving woman, silently and unquestioningly standing behind her husband, and it is through this imagination that he realises his love for Nanda, who takes him back despite his faults.

While the entire film follows the female characters through the narrative male gaze of the protagonist, the climax of Teen Devian brings forward the disciplinising mechanism of this gaze, wherein each woman and her identity is subjected to and is at the mercy of a male imagination. Hindi cinema in its early years essentially worked through this disciplinary male gaze through an overarching schema of romanticism. This problematic representation is intricately enmeshed with the project of nation-building that was being undertaken in the infant Indian nation.

In Teen Devian, a blueprint of the ideal Indian woman is drawn through the character of Nanda, who carried the very essence of what was envisioned as the Indian nation, a blend of rural simplicity and urban independence (under the dominant Hindu rhetoric), in a manner that the Indian woman is constant reminder of India’s rural roots and one who acts as a constant check to the urban thirst of the urban Indian man.

The newly independent Indian nation was invested with the task of constructing a national identity, a unique ‘Indianness’ and the representation of the Indian women in Hindi cinema, in a symbolic sense was to construct a national identity, a national culture, wherein the women of the society became a symbol of the nation itself. In Teen Devian, a blueprint of the ideal Indian woman is drawn through the character of Nanda, who carried the very essence of what was envisioned as the Indian nation, a blend of rural simplicity and urban independence (under the dominant Hindu rhetoric), in a manner that the Indian woman is constant reminder of India’s rural roots and one who acts as a constant check to the urban thirst of the urban Indian man.

Also read: Film Review: The Great Indian Kitchen – Serving Patriarchy, Piping Hot!

Nanda, although portrayed as an independent, working woman, is nonetheless subservient and peripheral to the public man that Dev is. She is a private woman in a public sphere, catering to a respectable public man and is hence seen as a good Indian woman, unlike Kalpana and Simi, who are public women, not subservient to the public man, thus viewed, through the man’s eyes, not as the ideal Indian woman.

Mass media (cinema in this context) has a rather captivating essence. For the viewer, cinema becomes a depersonalised experience of the personal self. While it is a reflection of the society, the society itself also becomes a mimetic archive through the mass medium of cinema. What is seen also becomes what is imitated. Cinema’s disciplinising mechanism culminates through this imitation.

In the context of Teen Devian and Hindi films in the formative years in general, the disciplining of the masses into Indians has taken shape (although not completely, but largely) through what was shown (and what was censored) through the popular medium of cinema. Through poetic dialogues and enchanting music, the subservient, peripheral ideal ‘Indian’ woman has been ingeniously constructed in the minds of the masses and intricately fabricated into the idea or the symbol of the Indian nation.

“One is not born, but rather, becomes a woman” as feminist author Simone de Beauvoir noted. Hindi cinema in its early years has contributed largely to this ‘becoming of an Indian woman’, through narratives seen, shown and controlled by the male gaze. For generations, commercial Hindi cinema has worked subtly, as an apparatus of disciplining the masses into a specific way of looking at the women in the society, and glamorised this disciplining gaze as values of the Indian woman, symbolic of Indian culture. Teen Devian is one such instance that I have discussed in this essay. The Devian or the Goddesses (in the Hindu belief system) are the objects of worship for the man, and only the ideal among them can be worshipped, which is to be determined by the man himself. I could point out multiple such films and bring those in the scope of analysis but that would only make this essay an oddly long one to read.

To assume that such problematic symbolic representations represent only a certain period of Hindi cinema would be incomprehensive. This gendered way of looking, pleasure seeking and displinising through cinema has been a strong force shaping Indian society and continues to be commercially exploited in cinematic representations even today.

Aindrila Chakraborty is a Ph.D. student of cultural anthropology at the University at Albany, State University New York. Her research interests are colonialism, migration and diaspora. She also loves to watch, read and unpack Indian cinema. You can find her on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.