Trigger warning: Mention of mental health, death by suicide

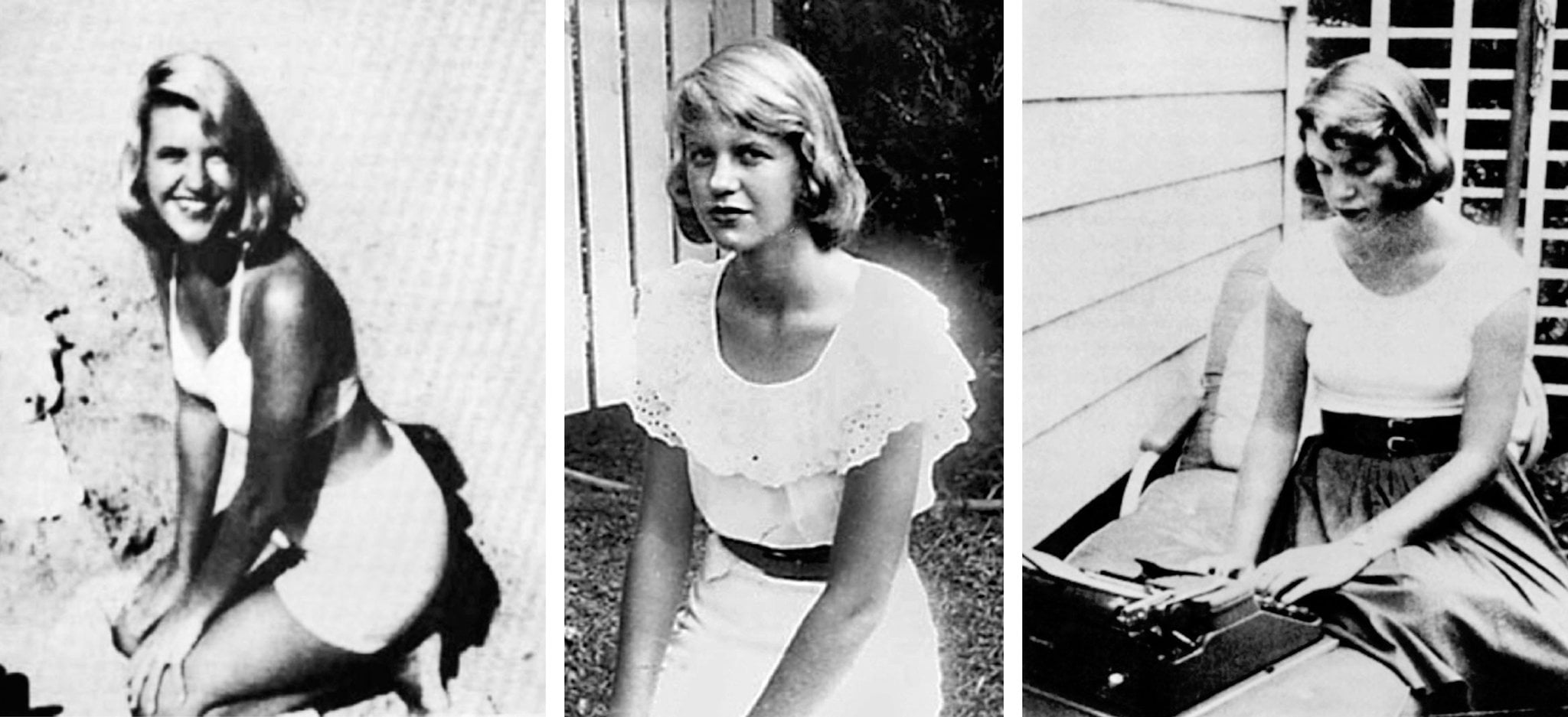

Most people who have heard of American poet, novelist, and short-story writer Sylvia Plath are familiar with the unfortunate fact that she was “the poet who placed her head inside a running oven“. The majority of Sylvia Plath biographies create a grim picture of the poet and present her as someone utterly obsessed with death. While information about her personal life, such as her tumultuous marriage to writer Ted Hughes, her unresolved conflicts with her parents, and her struggles with mental health are widely publicised, perhaps her craftsmanship is often side-lined.

Sylvia Plath’s poetry, written in an unabashed confessional form, seeks to depict strong emotions like devastation, despair, death, women’s struggles and much more.

Plath is considered as one of the most significant and dynamic poets of the 20th century. Her work is generally attributed to the genre of confessional poetry, along with the works of her fellow poets like Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton. In a 1962 interview, she indirectly puts the confessional movement in poetry into words: “this intense breakthrough into very serious, very personal, very emotional experience which I feel has partly been a taboo”.

Her peculiar style of writing is characterised by her use of turbulent imagery. She transformed ordinary everyday objects into terrifying things through her pen, “The vivid tulips eat up my oxygen“, she wrote. Diagnosed with clinical depression, Sylvia Plath used her gift of poetry to explore her own state of mind.

In an era where the stigma around mental health was immense, Plath unflinchingly wrote about her innermost mental anguish in a highly intimate manner. In her first poetry collection “Colossus”, published in 1960, she writes of sows and skeletons, fathers and suicides, the chaotic imperatives of life, and the icy longing for death.

With haunting depictions of the collective loneliness especially women face in the modern society, The Bell Jar has earned the stature of being an American classic. In the novel, Plath deals with the theme of mental health in a lucid and vivid manner. “To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is a bad dream ”

“A workman walks by carrying a pink torso. The storerooms are full of hearts. This is the city of spare parts”. The poems, so brilliantly written, convey layer after layer of meaning. Even while drawing her imagery from nature, her artistry seems so original, and possesses the power to thrill, delight, and shock. “Sun struck the water like a damnation. / No pit of shadow to crawl into, / And his blood beating the old tattoo I am, I am, I am…”

Sylvia Plath started writing poetry at the age of eight. Though she had a natural calling for poetry, she wanted to try her hand at writing prose as well. Her first and last published novel, The Bell Jar, came out in 1963. Like most of her works, The Bell Jar is semi-autobiographical and fictionalises the time Plath spent working for the Mademoiselle magazine in New York, during college. The novel is considered by many to be a second-wave feminist classic as the protagonist fights to earn a place for herself in the male-dominated world and also challenges the cultural, stereotypical norms of womanhood.

Also read: Book Review: The Bell Jar By Sylvia Plath

However, the novel later came to be criticised on the grounds that her White middle-class privilege made Sylvia Plath blindside the experiences of women from marginalised classes and third-world countries. The novel explores the dark corners of the human psyche as the protagonist Esther Greenwood slides into an intense, depressive episode.

With haunting depictions of the collective loneliness especially women face in the modern society, The Bell Jar has earned the stature of being an American classic. In the novel, Plath deals with the theme of mental health in a lucid and vivid manner. “To the person in the bell jar, blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is a bad dream.”

The very first page of the novel draws the readers in with its simple, genius description of the protagonist’s mental and emotional state. “I felt very still and empty, the way the eye of a tornado must feel, moving dully along in the middle of the surrounding hullabaloo.” Though the way the novel deals with the theme of mental health is brilliant, the novel hasn’t aged well, to say the least.

With numerous fat-phobic and racist comments, The Bell Jar is extremely problematic at times. With her insensitive descriptions of an obese woman “with a grotesque and protruding stomach”, the protagonist comes across as a fatphobic person, who often body-shames people around her. There is no dearth of racist comments in the novel, either. On one occasion, the protagonist looks into the mirror and thinks she looks “like a sick Indian” and on another occasion, describes her own mirror reflection as “a big smudgy-eyed Chinese woman staring idiotically into my face”. A Black character speaks English in a caricatured way and is physically assaulted by the protagonist, and further racist descriptions like “dusky as a bleached-blonde negress” are also found in abundance.

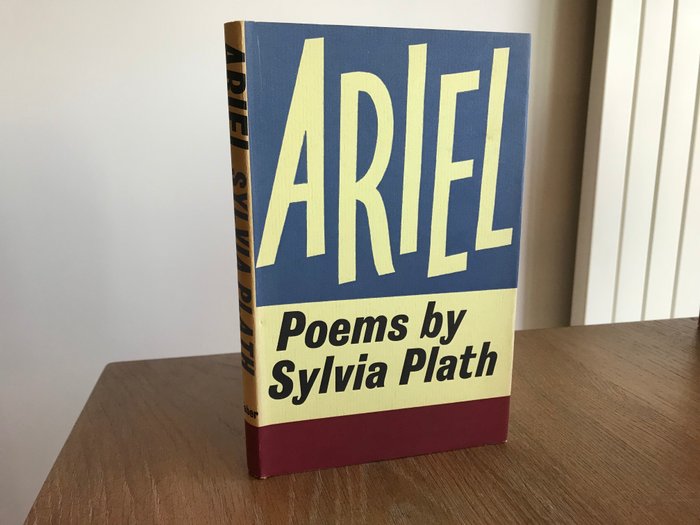

Sylvia Plath died by suicide at the age of 30, shortly after the publication of The Bell Jar. Her death perhaps remains the most remembered fact about her till date. A couple of years after her death, her second poetry collection, “Ariel” was published. She sought to write about issues which weren’t openly discussed in the world around her: trauma, frustration, sexuality, and more.

“The trouble was, I hated the idea of serving men in any way. I wanted to dictate my own thrilling letters.” Her journals, published posthumously as “The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath”, remains a literary favourite to this date and she succeeded in doing what she wanted to do all along: “let me live, love, and say it well in good sentences”

Having lived a troubled life, Plath chose poetry as a means to capture her pain. In a poem titled Lady Lazarus, she talks both about death by suicide and survival. “Dying/ Is an art, like everything else/ I do it exceptionally well”. The poem metaphorically talks about the difficulties of being a woman in the patriarchal world, and showcases the speaker’s refusal to succumb to societal expectations.

“Out of the ash/ I rise with my red hair/ And I eat men like air.” Helen Vendler describes Sylvia Plath to be “demonically intelligent”. Another poem titled Daddy presents her rage and frustration directed at an authoritarian father and an abusive husband who try to control her, filled with controversial references to the Holocaust.

Her poems challenge the traditional notions of womanhood, motherhood, and reality itself. In a particular poem, Tulips, the speaker speaks of her family as “baggage” as she lies in a hospital bed. “My husband and child smiling out of the family photo; / Their smiles catch onto my skin, little smiling hooks.” Voicing her struggles with mental health, Plath succeeds in expressing the inexpressible, questioning the nature of reality itself. “I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead. I think I made you up inside my head”.

Sylvia Plath’s intensely personal style is perhaps what makes her poetry feel so intimate and relatable. Written in lucid language, her poetry makes one relate to it and feel like they’re not alone in their struggles with mental health. Though she has been criticised on the same grounds as other second wave feminists, Plath undoubtedly highlighted ideas of women liberation and how the society has failed women.

“The trouble was, I hated the idea of serving men in any way. I wanted to dictate my own thrilling letters.” Her journals, published posthumously as “The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath”, remains a literary favourite to this date and she succeeded in doing what she wanted to do all along: “let me live, love, and say it well in good sentences”.

Also read: Where Are The Women Poets? Questioning The Canon Of Indian English Poetry

Featured Image: The New York Times

About the author(s)

Apoorva is currently pursuing her Master’s in English from Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. When she’s not re-reading the letters by Virginia Woolf, she likes to try her hand at scribbling poetry. Her areas of interest revolve around Feminist Theory and Absurdist Fiction. She can be found brewing tea at midnight, complaining about our Sisyphean existence