“We have a system where there is equality in misery, but no equality in prosperity,” says Prof. Anupama, as she scans the National Sample Survey (NSS) data on agricultural work and ownership of land in the state of Punjab. In the absence of any proper data on women farmers in Punjab, I was beginning to question the very notion of it. How is it that women are so political when it comes to protests, but you don’t find any data on them? “Because in Punjab kheti means jatt, which means ownership of land,” she says.

“Women got pushed to the back-end work once agriculture became dependent on the market,” says researcher Navsharan Kaur. “The process of sowing and harvesting has a lot of behind the scenes sambh sambhal, like making rotis for labourers or gathering dried cotton bales for firewood, which women began taking responsibility for. Similar to how they handled the backend work during the Delhi morcha,” she says, referring to the Farmers’ protest that lasted for 13 months on the borders of Delhi and saw massive participation by women.

The Head of Department of Economics at Punjabi University, Patiala, Prof. Anupama is the second woman HOD in the long line of men on the name board in her office, and in a state with hardly any organisations dedicated to women’s role in agriculture, she is one of the few academicians who are the source of any data or studies available on the subject.

In the mid-sixties, the seeds of the Green Revolution were planted in the state, which altered the landscape of the region for generations to come. With the Green Revolution came mechanisation, and agriculture got dominated by market-based activities. “As agriculture got more technology intensive and became more market driven, women got side-lined in the process,” Prof. Anupama explains. “When your entire system is focussed on production, it doesn’t matter if women get their due, own lands or are even represented.”

The entire spread of the Green Revolution was based on extension services, which means institutions like Punjab Agricultural University (PAU) and the Department of Agriculture conducted camps to educate farmers on new seeds, fertilisers, pesticides and technology. “This was a major area where even the policy makers had excluded women,” Prof. Anupama says, “as the entire spread of extension services focussed only on male farmers.” Extension services doesn’t stop women from attending camps but it doesn’t even encourage them. For example, in MNREGA it is mandatory for 30% workers to be women. Here there was no target or compulsion from the policy side.

Women unemployment resulting from the Green revolution is a largely ignored area. Data reflects that women are more engaged in supplementary activities in agriculture like tilling, weeding or plucking, which would qualify them as labourers and not farmers. As cultivators, women in Punjab account for a small percentage of 9.9% as opposed to men at 21.7% according to the 2011 census, and as owners of land, there is no fixed data, but believed to be under 5% in the state.

“Women got pushed to the back-end work once agriculture became dependent on the market,” says researcher Navsharan Kaur. “The process of sowing and harvesting has a lot of behind the scenes sambh sambhal, like making rotis for labourers or gathering dried cotton bales for firewood, which women began taking responsibility for. Similar to how they handled the backend work during the Delhi morcha,” she says, referring to the Farmers’ protest that lasted for 13 months on the borders of Delhi and saw massive participation by women. “But this is not to say that their relationship with land is broken. Their sense of ownership is complete.”

While many might argue that there is division of labour in work, Prof. Anupama says that the division of labour too has a determining factor – policy making. “It is convenient for a man to go to mandi because the system supports it. The policies have ensured it and were chalked out for men,” she says. “Our policies do not support a woman to go to mandi and spend the night looking after her produce. So if she wants to go to mandi, she will always seek a male counterpart.”

As wheat-paddy began accounting for more production and income for the state, area under oilseeds too declined, which is where most rural women found employment. The female work participation rate in rural Punjab recorded a new low as Census 2011 revealed. It declined from 19.1 percent in 2001 to 13.9 percent in 2011 and was quite low from the all India figure which stood at 25.6 percent in 2001 and 25.5 percent in 2011.

Though women got limited to their homes due to wheat paddy being tied to the market, they continued to engage in agriculture from the four walls of their homes. But their contribution mostly goes undocumented. Prof. Anupama says that the work women do either goes into unpaid labour or remains unaccounted for because it can easily be clubbed with housework, and most of it gets invisibilised as women themselves do not count it as labour.

“Even if she goes to the field to give chai, that is in kind wages for which another individual could be hired. But here it will never be counted,” she explains. “And there is also a problem with the way data is collected, as the boundaries between farm work and housework get blurred, especially in agriculture.”

The category of unpaid family labour in the NSS survey, for example, documents unpaid work by males but for females it gets clubbed into the self-consumption category and therefore remains undocumented, she elaborates.

Also read: Farmers’ Protests: The Past And Present Of Peasant Movements In India

While many might argue that there is division of labour in work, Prof. Anupama says that the division of labour too has a determining factor – policy making. “It is convenient for a man to go to mandi because the system supports it. The policies have ensured it and were chalked out for men,” she says. “Our policies do not support a woman to go to mandi and spend the night looking after her produce. So if she wants to go to mandi, she will always seek a male counterpart.”

Studies have shown that over time as agriculture became male dominated, women began shifting to dairy. “The entire milk economy is dependent on women,” says Navsharan Kaur. But even here the role of women remained underrepresented. Prof. Anupama says that “if a proper evaluation of unpaid work by women in Punjab state domestic productivity in dairy is done, their contribution accounts to about 35% of the total production.”

Participation in the protest

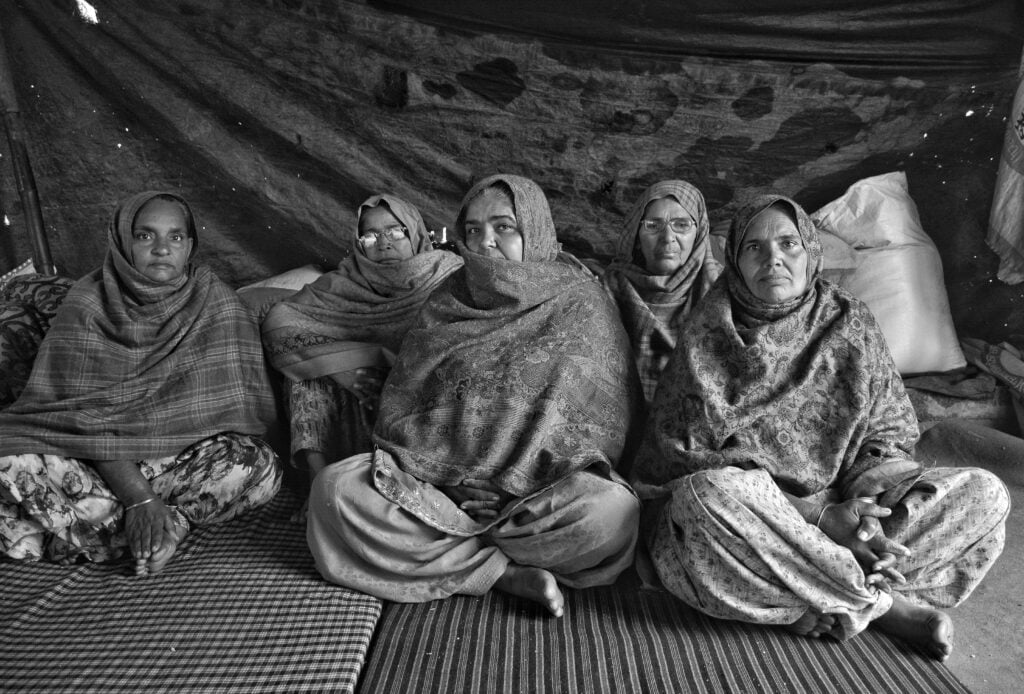

Participation by women in the farmers’ protest in Delhi was notably massive. Most Kisan unions have acknowledged that women played a crucial role in protest sites in Delhi and Punjab, and it would have been impossible to organise the protest without their efforts.

Despite not having any control over resources, women in Punjab have always been political and registered a massive role in protests historically right from India’s independence movement. Navsharan Kaur notes that women look at their role in the protest as a household unit and therefore defend that ownership as a family. And on their right of ownership to land she adds, “I thought maybe it’s my question and not theirs and they will take their own time to realise it.”

Living on the highways in Delhi was challenging, especially in the absence of bathrooms and toilets, but nothing deterred these women who took on these challenges happily.

In Punjab, women were collecting ration in villages, going door to door to mobilise more women, giving their attendance at the local morchas – on the nearby toll plaza or the Reliance pump, while in between returning home for a few chores.

When spoken to, most of these women spoke about suffering from “doori ghulami” or double slavery – one caused by the governing system which denies them their rights and the other by patriarchy, which denies them the remainder of their rights. Although suffering from systematic dominance from both sides, these women stood with ‘their’ men (as they said), demanding their rights.

“Women came out starkly in the protest when they said sadeeyan zameenan (our lands)”, says Navsharan Kaur. “Some journalists even asked them that the land is not in their name, to which they said ‘so what it’s not even in the name of their husbands and brothers yet (because the father is still alive).”

Despite not having any control over resources, women in Punjab have always been political and registered a massive role in protests historically right from India’s independence movement. Navsharan Kaur notes that women look at their role in the protest as a household unit and therefore defend that ownership as a family. And on their right of ownership to land she adds, “I thought maybe it’s my question and not theirs and they will take their own time to realise it.”

Mahila Adhikar Kisan Manch or MAKAAM is a voluntary organisation dealing in issues of women farmers nationwide. MAKAAM notes that no one had bothered to look at the three farm laws from the perspective of women and how they will impact them in an already patriarchal landscape.

“We noted that the new laws are pro corporate and anti-farmers and women will lose whatever little they have if the laws come into existence,” says C Ashalatha, Member of National facilitation team, MAKAAM.

Also read: How Farmers Continue To Stand Their Ground Despite Facing Atrocities By The State

According to MAKAAM, a farmer is any individual engaging and working with natural resources and includes labourers, livestock rearers, adivasis and fisherfolk into the category, a definition they borrow from National Policy for Farmers, 2007.

MAKAAM says the fact that not a single woman was present in the main leadership of Samyukt Kisan Morcha (SKM), the organisation leading the protests, is telling of the larger picture. “Despite many women leaders present, SKM remained a male organisation right until the end of the protest,” she says.

MAKAAM lobbied extensively to SKM to include women in its main leadership. Ashalatha says that these issues were raised to SKM during several zoom meetings, and they even wrote many letters. “They received our opinion but did nothing with it,” she says. According to her, most Kisan Unions are male dominated and therefore, look at women as ‘only numbers to be built in the protest’.

However, Ashalatha believes that the Delhi protest gave women a lot of visibility as many media outlets interviewed them and they spoke openly about their issues. “The women definitely have more agency than before but the important question is can they sustain it?”

The idea of land as male

Parmjit Kaur Pithoo, a farmer from Bathinda district in Punjab, lost her husband when she was 28 years old. She says her in-laws did everything in their capacity to ensure the ownership of land does not transfer to her, despite her being legally entitled to it.

“They harassed me, tortured me. My father-in-law made a false will for my husband and said they will look after my son and I can go back to my parents,” she says.

Parmjeet met a lot of organisations and ministers for help but no one even acknowledged her issue – her right to her 3-acre farmland. Finally, Parmjeet was put in touch with BKU (Ekta) Ugrahan by someone in her village who came forward with their support. They encouraged her to pursue the case legally.

Parmjit fought the case for years and finally won. But even then, her in-laws didn’t allow her to claim the land. In a final face off, her brother-in-law threatened to shoot her. “I told him he can shoot me but I am not going anywhere. That day they finally backed off and I got my land,” she says.

Under the Hindu Succession Act, a woman is entitled to her share of property from her in-laws and also from her parents. If she loses her husband then the property gets divided equally between the kids and her, and if the kids are minor then she will get the entire share. Kiranjeet says that in Punjab the life of young widows is miserable as they never end up getting a share of any resources while also having to look after their children, pay off a looming debt and live with societal bias. In her experience, the in-laws will never let the women get her share but will instead give it to the children if they have to.

Parmjit waged a similar battle for her house later and managed to get it in her name after years of additional struggle.

Today, Parmjit is the president of BKU (Ekta) Ugrahan’s women wing in Bathinda and says the farm union gets many such cases every year. “The common mentality is that if a woman is widowed young, she will remarry,” she says.

Widows being denied land after the death of their husband is a common phenomenon in Punjab. “Especially in the age group of 25 to 40, if a woman is widowed, most likely she will never get her share of land,” says Kiranjeet Kaur, who runs the Kisan Mazdoor Khudkhushi Peedit Parivaar Committee.

Under the Hindu Succession Act, a woman is entitled to her share of property from her in-laws and also from her parents. If she loses her husband then the property gets divided equally between the kids and her, and if the kids are minor then she will get the entire share. Kiranjeet says that in Punjab the life of young widows is miserable as they never end up getting a share of any resources while also having to look after their children, pay off a looming debt and live with societal bias. In her experience, the in-laws will never let the women get her share but will instead give it to the children if they have to.

In a joint study by three universities, the farmer suicides in Punjab between 2001 and 2017 were calculated at 16,606. This includes farmers and labourers. While surviving farming families are liable to a compensation of 3 lakhs by the state, only one third of these cases have been compensated. And even here mostly surviving widows suffer as the in-laws do everything for her to be denied the share.

Kiranjeet mentions that even the policy is not supportive of a woman pursuing her fight for a share. For the compensation to be processed the loan borrowed has to be from a government bank or institution, which is problematic. “Loans are possible only if there is an asset, which means land. Most families, especially labourers cannot even claim the compensation,” she says.

In the case of widows of labourers, Kiranjeet says that sexual exploitation is quite common. Sometimes these women are asked to ‘settle a compromise’ in exchange for a sexual favour.

The role of state

For the government to believe you are a farmer, land is a prerequisite, which means the system stands by the definition of a farmer that leaves the majority of those engaged in agriculture out of it.

“Most of the credit policies in agriculture are only for landowners. You can seek a loan only if you own land,” says Prof. Anupama. There has been a real lapse from policy makers in recognising that supplementary work in agriculture is an integral part of agriculture, without which it cannot sustain.

In southern states like Telangana and Kerala, women farm organisations have been able to mobilise and affect policy and framework. Initiatives like collective farming are brought in where landless women have access to a piece of land to cultivate. “But when it comes to availing any government schemes they are left out because they don’t own land,” Ashalatha says.

MAKAAM has been pushing for women who cultivate to be recognized as farmers and registered at panchayat land so they can access government schemes relating to agriculture. But these women at least have control over their produce.

However, in Punjab access to resources is difficult. Prof. Anupama says that women can try and claim their share on theka (when land is given on lease for cultivation) or when land is sold but when it comes to cultivation or waahi, the entire share will always go to the man.

Same is the case with ownership. The issue of land ownership will only be raked after the husband dies, not when he is alive, even though a woman is entitled to her share from her parents and also in-laws but mostly will never claim it, leaving it for her brothers or children.

Also read: Going Local with Women Farmers: Kodo-Kutki Cultivation Through SHGs

“What it represents is patriarchal control of resources and hence power,” says Navsharan Kaur. “But my question is where is the state in all of this? Someone has to voice it even to the state. And unless women themselves become that voice, it is not going to happen.”

Prof. Anupama says that the difference in outlook in North India from southern states towards land holding is because ‘North India has a larger land holding size’. “What it truly echoes is that whenever an activity becomes market oriented and there is more profit riding on it, men will come in to claim control.”

Anupama says that the difference in outlook in North India from southern states towards land holding is because ‘North India has a larger land holding size’. “What it truly echoes is that whenever an activity becomes market oriented and there is more profit riding on it, men will come in to claim control

Thnaks