When we start our education we rarely find a section in our history books about marginalised communities, and hardly on women from oppressed castes. Only in the Constitution of India chapter of my class 12th history book did I find any mention of Dalit scholars like Dr B.R. Ambedkar, as far as I recall. Today, as we move to our higher studies, scholars like Sharmila Rege have tried to bridge this gap in academia.

However, sadly India’s Gross Enrollment Ratio in higher education institutes was only 27.4 per cent as per All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE)’s data released in 2017-18. This makes us realise that not many are exposed to such historical writings. Thus, it is important to bring such writings in a concise yet worthwhile format for the masses to be able to study and understand the less-heard, yet very critical perspectives.

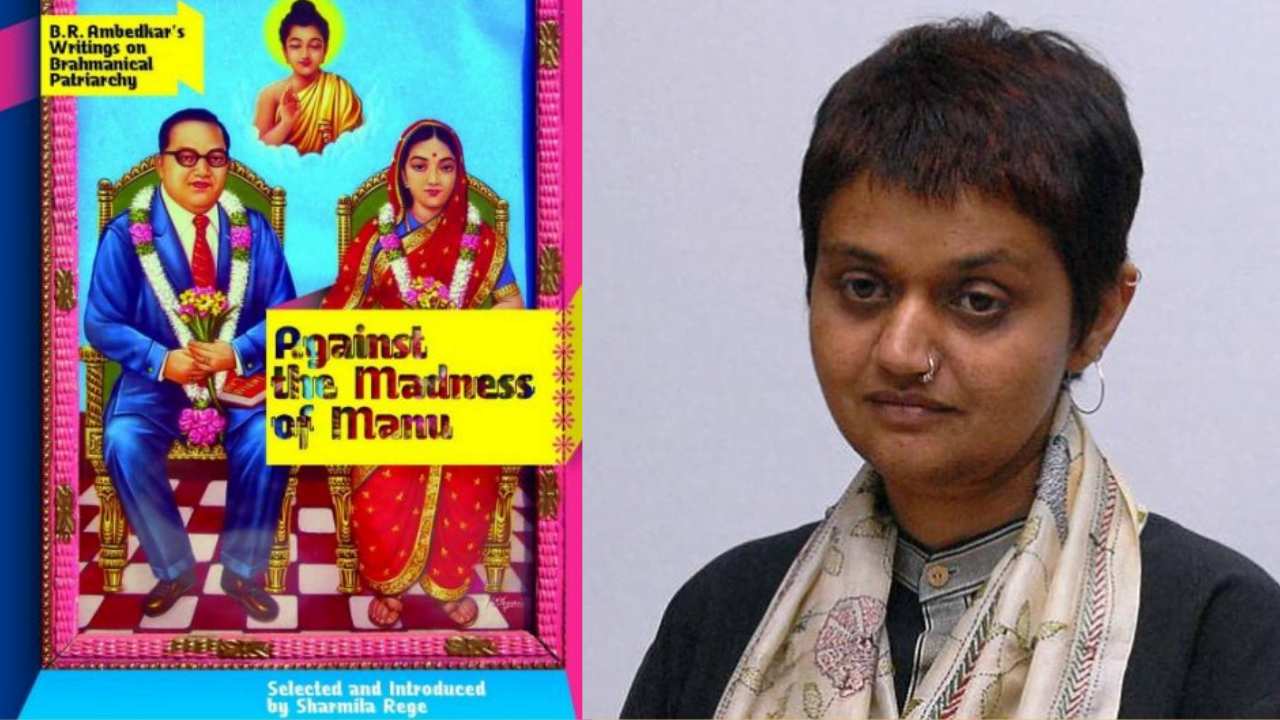

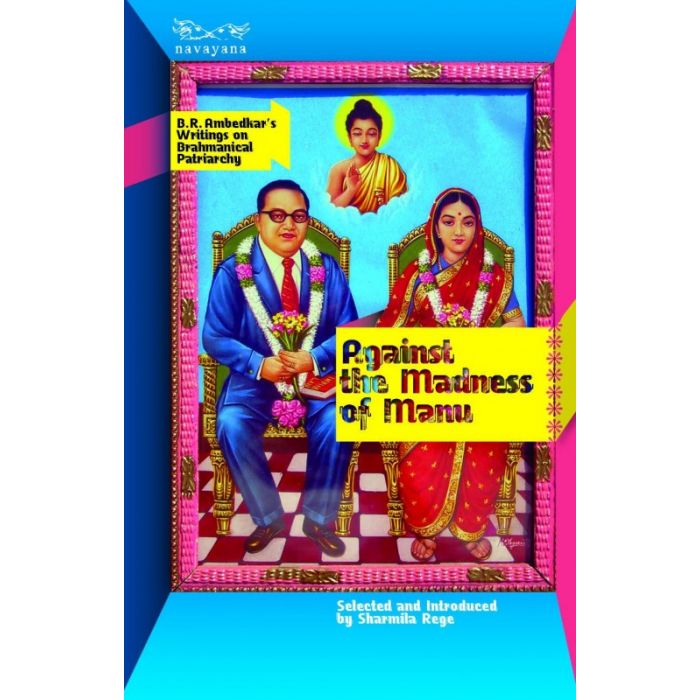

“Against the madness of Manu: Dr B.R Ambedkar’s Writings on Brahmanical Patriarchy“, is one such less-heard perspective in academia. It is the selected works of Ambedkar as introduced by late sociologist, Sharmila Rege. It was also her last work. As her obituary described, “Phule-Ambedkarite feminist Welder” Sharmila Rege shaped a unique Dalit perspective in our contemporary discourses on understanding feminism through various intersections like caste, class, sexuality and religion.

In her book, she critically examined Brahamical Patriarchy as analysed in Ambedkar’s essential writings and brought Ambedkar into our academic discourses again, or say at least in our higher education curriculums. Her interpretations of Ambedkar’s texts was one that neither sociologists nor feminists of our times imagined, before her. Her work helps us analyse how Brahmins and their twin patriarchy have been neglected by scholars for a long time.

Also Read: Sharmila Rege: Feminist, Sociologist, Welder | #IndianWomenInHistory

Rege highlighted the structural linkage of caste-based violence with sexuality and labour by rethinking Ambedkar’s text. This book also re-established the fact that endogamous practices of marriage had thrown Dalits to the margins which eventually backed the practice of cultural homogenisation. This was supported by the Brahmins’ assertion of faith in safeguarding their nationalist interests. Rege isn’t simply analysing Ambedkar’s arguments as they were, instead in her book she also illuminates why Ambedkar took a feminist take on the entire subject of caste.

Clearly, some terms in academia sound very persuasive but are useless if not used in relevant contexts. Sharmila instead of actually using such words describes these words, for instance, ‘intersectionality’ in great detail. As the book engages with the arguments proposed by Ambedkar bringing the importance of caste, class and gender as lived terms by experiences, not just reduced to mere slogans, Sharmila alerts us, to ensure this depth in our dialogues through this book. She also draws attention to the ways in which Ambedkar has been remembered and forgotten and then proceeds to select and annotate his writings, which, she felt, were particularly significant for feminists.

Also Read: Book Review: Looking Through Dalit Sahitya And Ambedkar

Throughout, the book she provides two contexts within which Ambedkar’s interventions can be located. The first is chronology, by that, Sharmila offers glimpses of today’s scholars and the then political developments that shaped the thought. As she identifies how Ambedkar, as early as 1916, identified the linkage between caste and endogamy which eventually leads to cultural homogenisation. Something that scholars of those times and even contemporaries still fail to reason out. Sharmila addresses this link with caste-based violence and atrocities faced due to Brahmanical Patriarchy in her essay in this book, titled: “The Inextricable Links Between Caste and Violence Against Women”.

Ambedkar saw caste’s exclusionary violence and subjugation of women as inherent in the very processes that lead to caste formation. This work is a constant reminder of the collective amnesia within academia, which has been the fate of most of Ambedkar’s writings for decades. Even though the last two decades have witnessed some changes in this regard, we still have a long way to go. Not just Ambedkarite reading but, Dalit studies and their literature as a whole need more recognition and concise interpretations like this one.

In this early intervention, Ambedkar, as Sharmila observes, moved beyond regarding caste as an imposition, or as a divine dispensation. In her editorial framing, Sharmila positions Ambedkar’s essay carefully—in terms of its contemporary context, written as it was nearly a century ago, and the ideas about race that often shaped understandings of caste—as well as the ways in which Ambedkar’s ideas were received, or rather not received, and remained unacknowledged for decades, till the 1990s.

Also Read: Book Review: Analysing Ambedkar: Towards An Enlightened India By Gail Omvedt

The second segment of the book draws on a set of Ambedkar’s writings, from the 1940s and 50s, which focused on the rise and fall of the Hindu woman, and the categorisation of the Shudra and the Ati-Shudras (erstwhile untouchable). Sharmila highlights the periodisation of early Indian history as worked out by Ambedkar worked out—in terms of a period dominated by the Aryan society of the Vedic period, followed by one when Mauryan influence lead to the rise of Buddhism and succeeded by Hindu India, the writings of Manu. Sharmila underscores silences within sociology and feminist formulations, some of which sometimes ironically unknowingly approximated the insights Ambedkar had arrived at.

In the next section of the book, Sharmila covers Ambedkar’s engagement with the problem of surplus men and women that leads to gender asymmetry in the graded structure of caste. Also, the reasons for Sati and widowhood were very well stated. Ambedkar throughout the exploratory study tries to find the genesis and mechanism of the Brahminical patriarchy and its various institutions that re-enforced ideas and practices of social discrimination and exclusion of marginalised women. The very last section talks about the madness that Manusmriti.

Sharmila’s interventions throughout the book are very thoughtful from the sharp contrast that she brings out in Ambedkar’s tone in the rise and fall of the Hindu woman, (second section of the book) where Manu instead of the Buddha was held to be responsible for the downfall that Ambedkar was tracing. In the first instance, as we have seen, Ambedkar argued against viewing caste as a creation of Manu. In the second instance, he was projected as being responsible for the subordination of women.

Given that caste and gender were intertwined in Ambedkar’s understanding, how do we grapple with this change? Sadly, we no longer have the luxury to listen to Ambedkar or Sharmila’s opinions on this issue, except through their books. All we can do is add such alternative perspectives into our curriculums to broaden our horizons. Broaden our understanding of the discourses revolving around the intersectionality of feminism, gender and caste-based violence and graded structure of inequality against the marginalised communities, so that the historical wrongdoings that are being committed to date can be put to an end forever.

About the author(s)

As an independent journalist, writer, and aspiring documentary filmmaker, Stuti covers about social and political issues. Interested in development journalism she also highlights issues on human rights, gender, education, unemployment, law and others. She aims to start her own news media initiative in the future to transform the way development is covered and discussed in the news.