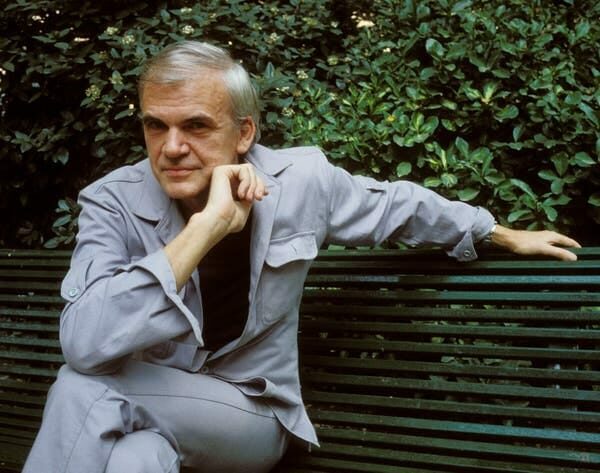

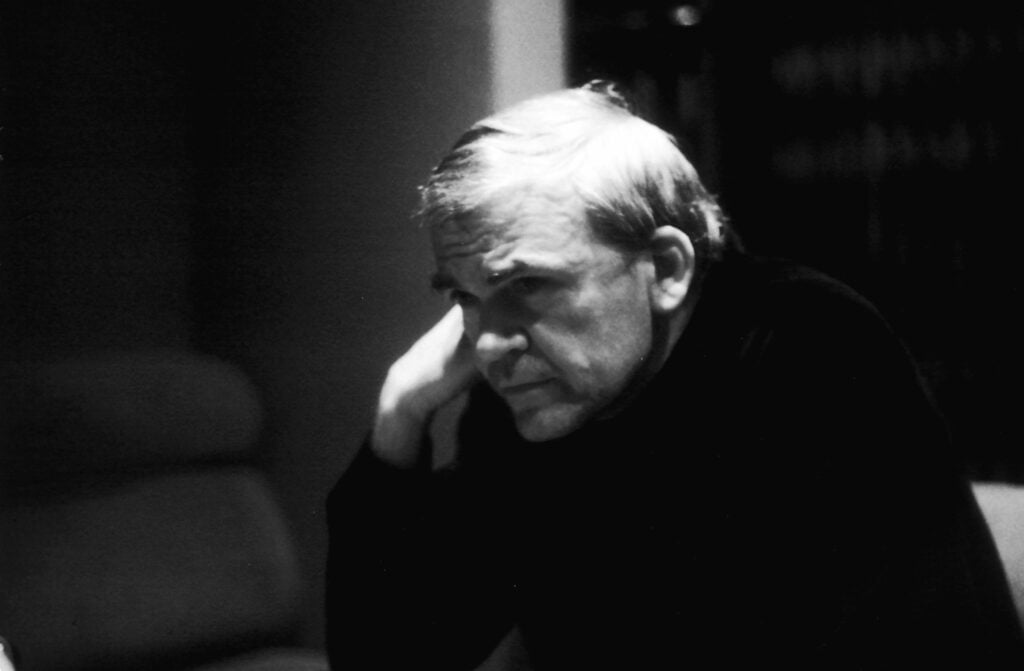

On 11th July 2023, Milan Kundera passed away quietly. The Czech novelist, short-story writer, playwright, essayist, and poet is known for his caustic humour, philosophical mind games, inimitable irony, erotic narratives and most importantly being one of the writers on the reading list of a non-conformist teenager. But, like Charles Bukowski or William S Burroughs, most writers on this unofficial list unsurprisingly fail women – does Kundera’s work, too, attest to that?

In the last decade or so, Milan Kundera’s work has silently taken a step under the veil of oblivion. The relevance of his work or the characteristic caustic tone did not seem to match the world that was changing at a diabolical pace. His hopelessness about the world was evident in a famous interview with Philip Roth, where he said: ‘the totalitarian world, whether founded on Marx, Islam or anything else, is a world of answers rather than questions… It seems to me that all over the world people nowadays prefer to judge rather than to understand.’

While most of his work pushed to question knowledge – his view of women or the nature of heterosexual relationships were wrought in the very absolutism he so detested.

While most of his work pushed to question knowledge – his view of women or the nature of heterosexual relationships were wrought in the very absolutism he so detested. Yet his misogyny is claimed to be a searing critique of misogyny. In Kundera’s words: ‘Things are not as simple as you think.’ Before the feminist reader can be infantilised, it is important to find the women in Kundera’s work and see how they thrive in his world.

Portrayal of men and women in Milan Kundera’s novels

The men in Kundera’s novels are painted in harsh colours – dominant, hurtful and egoistical. Ludvik from Kundera’s popular novel The Joke is a vengeful womanizer. The irony of the story lies in Ludvik’s attempt at revenge against his former friend Pavel, but the pawn in the game of masculinity is Pavel’s wife, Helena.

While the novel revolves around the communist regime – Ludvik’s political anger is turned into a fragrant bloom of vile misogyny. Throughout the book women have been portrayed as alien to being human. ‘The way women are’ is constantly defined by maxims like ‘no woman can be content for ever with puppy love‘.

Now, one may question how does Ludvik’s or Helena’s voice define Kundera’s – when writers are indeed crafting characters. The problem is not that a particular character might view women like that but that all four characters in the book seem to be following the common worldview about the idea of a woman. The absolute voice of Kundera’s understanding of women rings through all the characters.

The perpetuation of patriarchy in Milan Kundera’s literary world

Milan Kundera’s most popular work The Unbearable Lightness of Being shows similar symptoms. The world of Tomas and Tereza is an overwhelmingly masculine world. The novel is heavy on philosophical reflections and musings – all the while using the male pronoun. Universal metaphysical questions are drenched in the colour of a gender – ‘He has also learned that the soul is nothing more than the gray matter of the brain in action.‘ The novel upholds a system where women are oppressed and trivialised in a patriarchal regime. Kundera’s ironic voice does not choose to celebrate it per se nor does it give litheway for any respite.

The novel upholds a system where women are oppressed and trivialised in a patriarchal regime. Kundera’s ironic voice does not choose to celebrate it per se nor does it give litheway for any respite.

Having said that, the narrative unemotionally paints the picture of patriarchy that is not limited to men. Tereza’s mother embodied the cycle of patriarchy that lives through the women it subjugates. ‘Tereza’s mother never stopped reminding her that being a mother meant sacrificing everything. Her words had the ring of truth, backed as they were by the experience of a woman who had lost everything because of her child. Tereza would listen and believe that being a mother was the highest value in life and that being a mother was a great sacrifice. If a mother was Sacrifice personified, then a daughter was guilt, with no possibility of redress.’

The condition of Milan Kundera’s women mirrors the real world

While the women were quelled and subdued, the men were the kings of their will. ‘Was he genuinely incapable of abandoning his erotic friendships? He was. It would have torn him apart. He lacked the strength to control his taste for other women. Besides, he failed to see the need.’ Tomas continues to be unfaithful without censure.

Tomas’ love for Tereza is punctuated with dedication and genuity but he cannot seem to help himself. Society’s disparate treatment of the two genders in Kundera’s world is congruent with the reality of the world. Women are secondary characters to help the men journey through the narratives of Kundera’s work. While Kundera offers explicit portrayals of both masculinity and femininity, sparing none from his mordant quality – his feminine narratives conform to social standards and stereotypes. Patriarchy reigns in his world and there is not an ounce of respite or rebellion against it. One wonders what that says about a writer whose political voice has been famously known to be defiant.

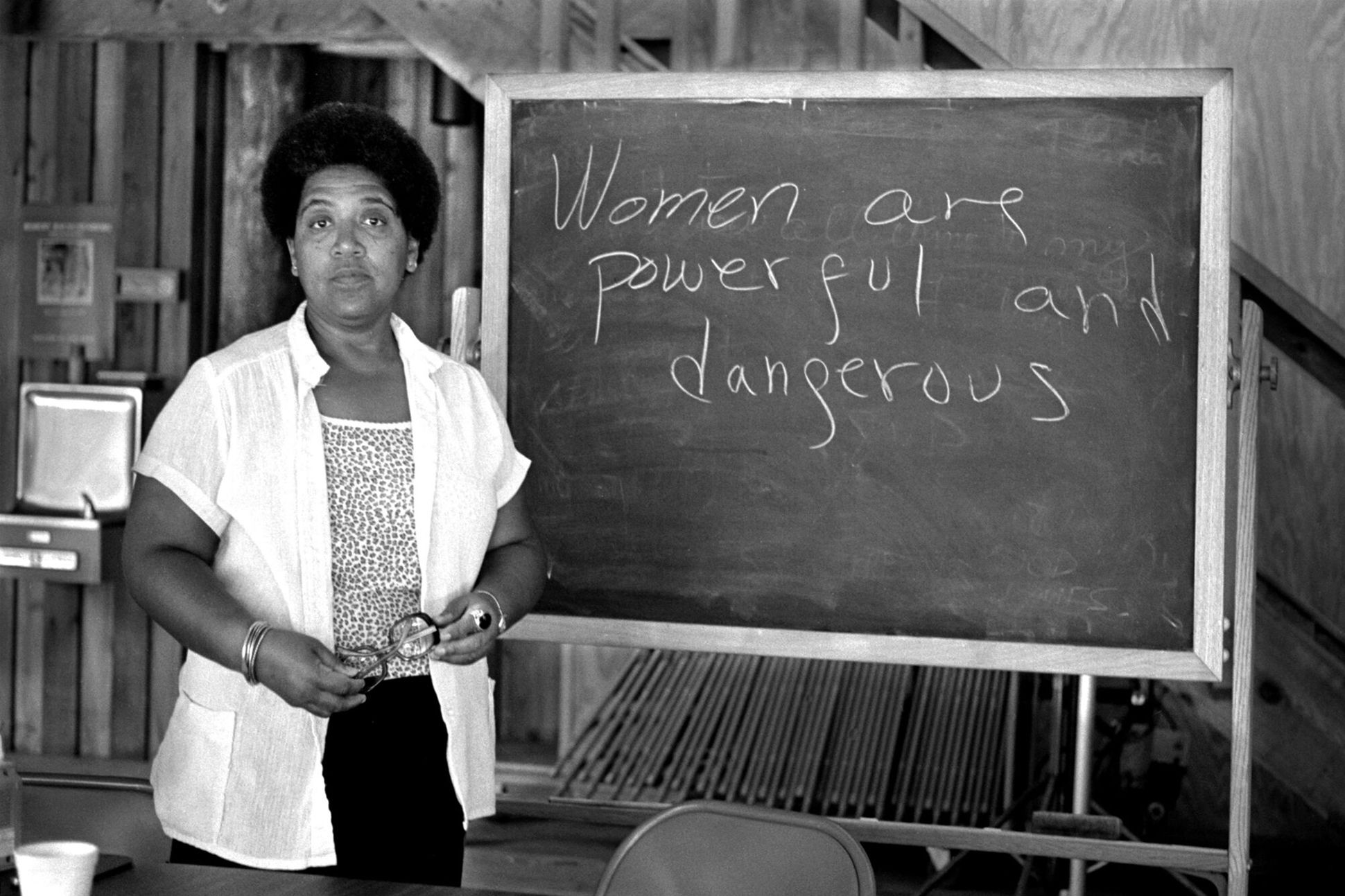

The problematics of men writing women

The fictional Boccaccio in Kundera’s The Book of Laughter and Forgetting says, ‘Misogynists don’t despise women. Misogynists don’t like femininity. Men have always been divided into two categories. Worshipers of women, otherwise known as poets, and misogynists, or, more accurately, gynophobes… Worshipers revere women’s femininity, while misogynists always prefer women to femininity. Don’t forget: a woman can be happy only with a misogynist.’

Although Kundera projects women in the central plot – they seem devoid of any agency or power, doused in outdated sexism, ageism and abject misogyny.

Probably the world has had enough of white men’s opinions and imaginations about women, no matter through how many fictional characters.

Although Kundera projects women in the central plot – they seem devoid of any agency or power, doused in outdated sexism, ageism and abject misogyny.

Kundera’s mastery over his language and political wit often overtakes the raging misogyny that his works repeatedly underline. If a reader wants to, they can wrap all of it up in the defence of a writer who excels in irony. While the literary world mourns the loss of a writer who was forgotten too soon, it is important to take note that more than his style or metaphysical jokes or political commentary, Kundera’s masculinity did not age well. Here is to Kundera’s women in his own words – ‘Fortunately, women have the miraculous ability to change the meaning of their actions after the event.’

If only MRAs would diversify their reading list!

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo