Bollywood movies have contributed enough in fueling our imagination about the courtesan culture through its vibrant depiction of ‘tawaifs’. The tawaif culture in India existed in the medieval period and they formed the popular courtesan class primarily in charge of entertaining the royalty and nobility with their subtle talent in numerous art forms. Most civilisations around the world in the past have been exposed to the rich courtesan culture- from Korea’s ‘Gisaeng’, Japanese’s ‘Oiran’ in the east to Greece’s ‘Hetaira’ in the west. Similarly in ancient India as well there existed an opulent courtesan class called the ‘Ganika’.

One common trait that tied all of these women in a same thread was that, they belonged to the intelligentsia section of the society. They were the actual “beauty with brains” engaging themselves in political and diplomatic affairs while at the same time entertaining the ‘elite’ class of men using their various skills.

The position of Ganikas in ancient Indian society

Traditionally, Ganikas were part of the class of sex workers in ancient India. However, sex workers were not a homogenous group during this period. Ancient Indian texts like Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra, Kautilya’s Arthasastra categorised them into various groups based on their skills and responsibilities. It is within these categories, the Ganikas are accorded the highest rank that distinguished them from other public women. While talking about sex workers, the one conventional image that appears in the general mind is that of a “seductress”. Ganikas in ancient India certainly had more roles to play than that of a seductress. They were the elite courtesans occupying respectable position in urban society.

Replete with qualities, these “city women” (nagarika) were not entirely free from common prejudices and other pejoratives since they were also part of the public sphere. What distinguished them was their intellectualism and accomplishments in various art forms. Their role therefore was not just to sexually satisfy her rich clients or act as the “object of men’s desire”.

Ganikas had unrestrained access to elite education, usually reserved for the prince or the princesses. Through this education, Ganikas became proficient in various shastras as well as other vocational skills.

Ganikas had unrestrained access to elite education, usually reserved for the prince or the princesses. Through this education, Ganikas became proficient in various shastras as well as other vocational skills. They used their knowledge thus acquired in popular political assemblies or literary conferences. They learned Sanskrit that was reserved for the upper class of men and even communicated in it, thus placing herself at par with the literati class. Vatsyayana has devoted an entire section of Kamasutra to the behaviour, mannerisms and rules that a Ganika was required to learn in order to earn wealth and fame in society.

According to the text, a Ganika must master, in total, sixty-four art forms or angavidyas that included being able to read, write and compose, playing various musical instruments, erotic art, singing, dancing, poetry among many others. A Ganika was supposed learn seventy-two arts and sciences according to one Jain text that added the necessity of learning arithmetic, the game of dice, riddles, making of perfumes, jewelry, garland, soap, medicines and many more. This education was received from a very young age by them in gandharvasalas where they were trained to earn the title of Ganika by acquiring these skills.

The rights that the Ganikas enjoyed in society was traditionally denied to ‘kulastri’ or ‘kulavadhu’ (literally, ‘wife of the household or clan’ or ‘rightfully married wife). This is because, Ganikas were independent public women free from the ‘pativrata’ ideology that tied the kulastri within the confinement of their household. Regarding the portrayal of the status of the ganikas in society, there were visible differences between the Brahmanical texts and the Buddhist texts. The Smritis and Dharmasutras have portrayed the ganikas quite antagonistically.

In this normative literature they were tagged as “social evils” where killing them was not considered a crime and Brahmanas were even warned against receiving offers of food from them. While in Buddhist texts they were hailed as ‘nagara sobhani’ (jewel of the city), whose presence increased the pride of the nagara. The Brahmanical law books have blurred the lines that separated the categories of sex workers and depicted them as vile creatures. However, these texts contain definite laws and regulations for them which is enough to prove their institutionalised position.

Ganikas as portrayed in classical Sanskrit literature

The classical literary works of ancient India have presented the Ganikas as ideal women whose attention and companionship were coveted by men of upper class. In their works of fantasy, the authors of classical literature have broken the barriers of the dharmasastric norms by portraying “romantic” relationship between a courtesan who belonged to the “asocial” world and a man of the city who belonged to the “social” world, thus merging both the worlds into one.

In their works of fantasy, the authors of classical literature have broken the barriers of the dharmasastric norms by portraying “romantic” relationship between a courtesan who belonged to the “asocial” world and a man of the city who belonged to the “social” world, thus merging both the worlds into one.

This scenario is very well depicted in the popular classical play Mrichchhakatika by Sudraka. The acts of the play have narrated the blooming love between Vasantasena, a rich courtesan of Ujjayini and Charudatta, an impoverished Brahmin of the same city. This socially “scandalous” relationship as portrayed in the play not only help us to understand the actual position of a ganika in society but it also proves the fact that such affairs were not unheard of in ancient India.

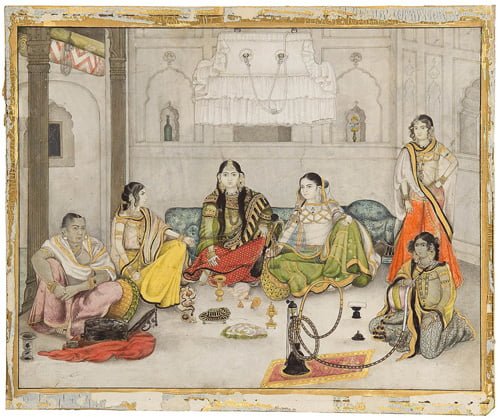

In Mrichchhakatika, Vasantasena’s glamourous lifestyle is well portrayed through her luxurious household that is compared with ‘kuberabhavana’. She is shown bejewelled with ornaments and wealth compared to Charudatta’s wife Dhuta who considers her husband to be her sole ornament. Here is the dichotomy clearly represented between Vasantasena, a rich independent public woman and Dhuta, a woman of the household, dependent and tied to the shackles of ‘pativratadharma’.

In Mrichchhakatika, Vasantasena’s glamourous lifestyle is well portrayed through her luxurious household that is compared with ‘kuberabhavana’. She is shown bejewelled with ornaments and wealth compared to Charudatta’s wife Dhuta who considers her husband to be her sole ornament.

Once Vasantasena was married to Charudatta, she had to give up her jewels and put the shackles of the familial world on her feet. Despite being a rich, respected Ganika of Ujjayini, Vasantasena had to face the social stigma even in her lover’s house where she was not allowed to enter in the inner quarters being a courtesan.

How did the Ganikas became wealthy?

Ganikas were a state controlled institution during Mauryan period and they were under the constant supervision of the Ganikadhyaksha (superintendent of courtesans), They were provided with education and training at the state’s expense and were maintained through a salary of a thousand panas. Their most significant task according to Arthasastra was spying on their rich and influential clients to extract information using their skills and knowledge.

They lived-in state-owned palaces, provided with handmaidens and servants to wait upon them. However, they were required to pay the state a certain amount of their total earning as tax. Both archaeology and textual evidences show the rise of urban centres like Pataliputra, Vaisali, Varanasi, Ujjayini, Campa etc. These urban centres that witnessed burgeoning trade made way for the rise of wealthy merchant class who poured huge amount of money in the guilds of Ganika. Buddhist texts refer to the exorbitant fees charged by Ganika Ambapali that resulted in a dispute between Vaishali and Rajagriha.

These texts also mention about other highly accomplished Ganikas who charged high fees per night like Salavati of Rajagriha, Vasavadatta of Mathura. Their access to immense wealth and resources is attested by inscriptional evidences that record generous donations made by these women in patronising sacred architecture as well as buildings for public welfare. They could make such huge expenditure partly because of their social position and also because they were outside the familial links that identified a woman as wife, mother or daughter. They earned the wealth independently at their own accord using their skills and even ran picture galleries by themselves.

Enriched in both knowledge and wealth, Ganikas were undoubtedly a threat to the patriarchy. They were outside the precinct of the sexual restrictions, ‘stri-dharma’ and ‘pativrata-dharma’ imposed on women by the patriarchal society. Elegant and accomplished, the world of ganikas was matrilineal, dominated by women, which was unparalleled in ancient world.

References:

- Bhattacharji, Sukumari, ‘Economic Rights of Ancient Indian Women’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 26, No. 9/10 (Mar. 2-9, 1991), pp. 507-512.

- Saxena, Monica, ‘Ganikas in Early India: Its Genesis and Dimensions’, Social Scientist, Vol. 34, No. 11/12 (Nov. – Dec., 2006), pp. 2-17.

- Darshini, Priya, ‘Status of the Ganikas in the Gupta Period: Change or Continuity?’, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 64 (2003), pp. 167-172.

- Shah, Shalini, ‘ In the Business of Kama: Prostitution in Classical Sanskrit Literature from the Seventh to the Thirteenth Centuries’, in Vijaya Ramaswamy (ed.), Women and Work in Precolonial India- A Reader, SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd, New Delhi, 2016, pp. 392-417.

- Bhattacharji, Sukumari, ‘Prostitution in Ancient India’, Social Scientist, Vol. 15, No. 165 (Feb. 1987), pp. 62-97.