Cultures throughout ages and around the world seem to have made considerable efforts to define the “ideal body” of a woman. This is well reflected in several literary works of the past as well as in ancient sculptures and paintings. The celebrated Sanskrit author, Kālidāsa of ancient India in almost all of his plays and poems has attempted to portray the scenario where his male protagonists quite spontaneously fall in love while feeling drawn towards our heroine’s “perfect body shape”.

The celebrated Sanskrit author, Kālidāsa of ancient India in almost all of his plays and poems has attempted to portray the scenario where his male protagonists quite spontaneously fall in love while feeling drawn towards our heroine’s “perfect body shape”.

Thus, in his very first play, Mālavikāgnimitram, the male protagonist, king Agnimitra, on realising his love for the court dancer, Mālavikā, appreciates and idealises the perfection of Mālavikā’s body- her ‘bent bamboo’ shaped arms, her ‘full, soft, firm and smooth’ breasts, her ‘thin’ waist, ‘curved, broad’ hips and lastly her ‘arched’ toes and feet. Kālidāsa quite lucidly through his writing assisted Agnimitra in casting his eyes upon the ‘beautiful’ body of Mālavikā, thereby consciously blurring the lines between love and lust. This objectification of Mālavikā’s body dates back to fourth or fifth century CE i.e., approximately 1600 years ago. This aptly reflects the heteropatriarchal mindset of the ancient Indians and the fact that male gaze had been pervasive in society throughout history.

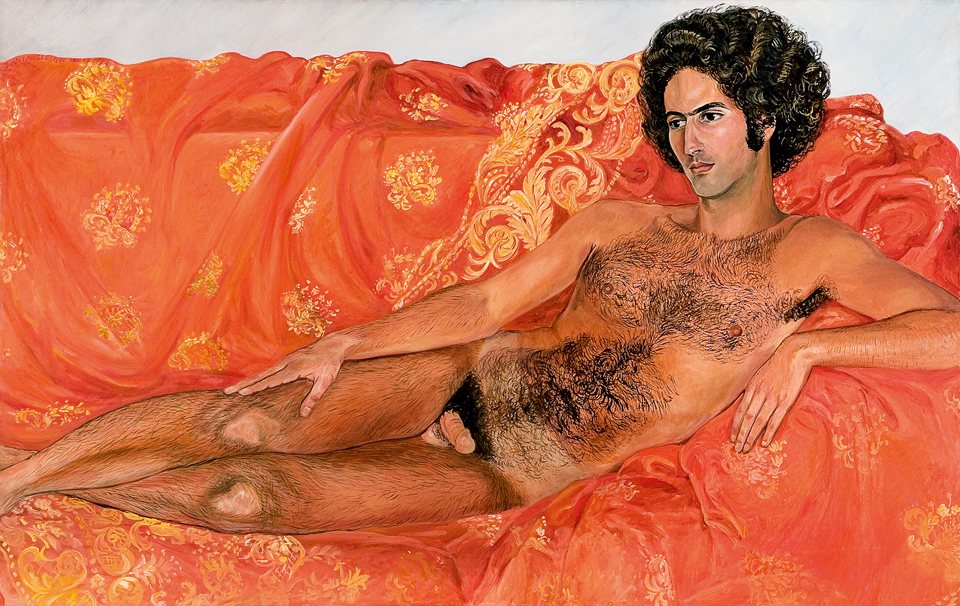

Surasundaris and the spectator’s gaze

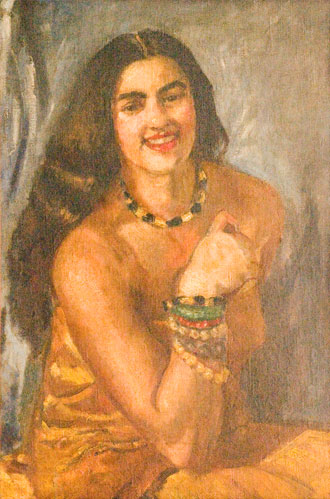

On visiting any early Indian sacred architecture, be it Brahmanical, Buddhist or Jain, one would most certainly come across the three-dimensional figures of women carved in high relief resembling the description of Mālavikā’s body. These sensuous sculptures of female figures adorning the exterior walls of the temples invariably have slender waists, round and full breasts, broad hips and they stand in sinuous tribhaṅga positions (bent at three sides of body-hips, knees, shoulders and neck).

Collectively called as ‘Surasundaris’ (literally, beautiful, celestial maidens), these sculptures with voluptuous body parts that are associated with fertility arguably beautify the architectures according to a ninth century CE art treatise Silpa Prakasa. They are variously shown engaged in a particular kind of activity like holding a mirror, or smelling a lotus flower, some can be seen putting on anklets, making their hair or colouring the undersurface of their feet while gently raising them upwards. In every case they appear immersed in their respective worlds unbothered about the spectators’ gaze towards them.

Inevitably, these figures are the creations of the male gaze that we hitherto encountered in Agnimitra’s description of Mālavikā’s body in Kālidāsa’s play Mālavikāgnimitram. This hyper-sexualisation of women’s bodies is a consequence of a heteronormative society which again is a perpetual norm. These Surasundaris might well have served some kind of ritualistic propitious functions; however, this cannot be a justifiable defence for giving them a distinct ‘provocative’ body visibly fashioned out of men’s desire since, it will eventually make us question the definition of ‘beauty’ applied to a woman even though that woman is a celestial damsel.

Fetishising the ‘celestial beauties’

The semi-divine sculptures of Surasundaris that form an integral ornamentation of every ancient Indian architecture is represented in all its passivity disclosing both the sculptor’s and the patron’s gaze that fetishises the bodies of these women. Scantily dressed, bejewelled, with hair done neatly, these women, also called ‘alasa-kanyas’ in another form (literally, lazy young maidens), are associated with eroticism and fertility and their representation indicates that, they are as well made to serve the purpose of enchanting a man or any other possible spectator with their sensuous beauty.

The sculptors were indisputably male owing to the time period we are dealing with; however, the patrons were not necessarily men as inscriptional evidences of the existence of female patrons of art have also been found. The central thought is- a woman can and is capable of sexualising other women and therefore in a patriarchal society there exists “female patriarchs” as well who uses their gaze to sexually objectify women. While viewing any art, the perspective of both the artists and the beholders matters and therefore it is essential for us to understand the obscured intention behind the spectator’s gaze.

The Brahmanical temples, Jain temples and Buddhist sacred architectural complexes house images of ‘celestial beauties’ carved in niches and recesses of the interior and exterior of the walls. The appearance of the figures, although subjected to sexual objectification, in sacred structure along with other semi-divine figures as well as erotic sculptures might present a convincing philosophical argument about them being insignia of auspiciousness. Of the extant monuments where well-preserved Surasundaris could be viewed are found in the Khajuraho temple complex, the temples of Orissa among many other sites across the subcontinent.

Surasundaris and voyeurism in ancient Indian art

The notion of male gaze in art was first brought by celebrated film theorist Laura Mulvey where she projected her understanding of the dichotomies and polarities of an active male who was the spectator and a passive female who was the spectacle. The Brooker Prize winner art historian, John Berger presented a somewhat similar ideology in the popular BBC program Ways of Seeing. In the second episode of this television program, he explained how a spectator’s gaze shapes an art.

There is however no doubt that in the shaping of the female figures with big breasts and narrow waist, the role of subservience was given to women and the dominant role was claimed by men as a validation of his masculinity. This subservient role was of fertility.

According to him, the spectator is always a male and the spectacle who is a female is treated as object of voyeurism and her role is subjected to passivism. There is however no doubt that in the shaping of the female figures with big breasts and narrow waist, the role of subservience was given to women and the dominant role was claimed by men as a validation of his masculinity. This subservient role was of fertility.

Women have been associated with fertility since prehistory. This association is related with prosperity and abundance and celebration of motherhood. There is no disagreement to this association; however, the dissension lies in the way these women have been presented in art. For example- in Kālidāsa’s Mālavikāgnimitram, our love-struck king Agnimitra wonders why the ashoka tree could not bear fruit despite being touched by the foot of one who has ‘slender’ waist (referring to his lover Malavika). The ashoka tree was metaphorically associated with fertility in ancient India and there was a prevailing belief that trees can bloom just by a woman’s touch.

Thus, we find, adorning the railings of Buddhist stupas several semi-divine sculptures equated with fertility like Salabhanjikas, Yakshis standing in a particular position holding the branch of a sal or an ashoka tree respectively. Here again the question is of projection of the ‘curves’ of their body which is clearly exaggerated. There exists epigraphical evidence of a nun who patronised the construction of one of the pillars of the railing of the Bharhut stupa bearing the relief sculpture of Sirima devata, a semi-divine figure. The figure is highly sensuous and provocative in character. She adorns heavy jewellery; her upper body is completely exposed showing the usual ‘round’ ‘full’ ‘big’ breast and extremely narrow girdled waist. Such idealised figure defining the feminine beauty was created here even though its donor was a nun. A possible explanation for this could be that- the creation of such sculptures depended on the sculptor’s gaze or the fact such figures represented the predominant mentality regarding the “ideal” feminine beauty.

The cave paintings of Ajanta that depicts scenes from Jatakas (stories of the previous births of Buddha) have similarly portrayed nude or semi-nude women and sexualised the ‘curvatures’ of their body. If the sexualisation of women’s bodies in sculptures and paintings is not a purposeful construction of a patriarchal society made and meant for spectator to derive voyeuristic gratification and to establish a beauty standard for women, what else could be the meaning behind such idealisation?

If the sexualisation of women’s bodies in sculptures and paintings is not a purposeful construction of a patriarchal society made and meant for spectator to derive voyeuristic gratification and to establish a beauty standard for women, what else could be the meaning behind such idealisation?

Whether women should remain clothed, or have their body parts exposed are determined by the patriarchal society and this is well explained in Dharmasastra, a text highly patriarchal in nature. In the text it is prescribed that a woman should cover her naval and legs entirely, whereas in their public display they are portrayed completely in an opposite manner.

The architectural treatise Shilpa Prakasha talks about the sixteen types of Surasundaris that would purportedly bring fortune and prosperity if adorned on temples and palaces. This association of women with fortune is very well received, revered and there is no objection. The objection is in the thought and portrayal where it is viewed that a woman’s raison d’etre is “achieving” a ‘curvaceous body shape’ and the utilisation of it in her reproductive capability, thereby blending her gender and biological role. This obsession with women’s body is ubiquitous in visual art in all eras and generations.

References: –

- Bawa, Seema, ‘Gender in Early Indian Art: Tradition, methodology, and problematic’, in Parul Pandya Dhar (ed.), Indian Art History- Changing Perspectives, D.K. Printworld and National Museum Institute: New Delhi, 2011, pp. 111-119

- Bawa, Seema, ‘From Aditi/Laksmi to Dugdhadharini: A Gendered Analysis of Iconography in Post-Mauryan Art’, Vol. 63 (2002), pp-121-137.

- Berger, John, Ways of Seeing, Penguin: London, 1972.

- Dehejia, Vidya, ‘Issues of Spectatorship and Representation’, in Vidya Dehejia (ed.), Representing the body- gender issues in Indian art, Kali for Women: Delhi, 1997, pp. 1-22.

- Mulvey, Laura, Visual and other Pleasures Palgrave: New York, 1989.

- Reddy Srinivas, trans. 2015. Kālidāsa’s Mālavikāgnimitram. Translated as Malavikagnimitram: The Dancer and The King (Srinivas Reddy, Trans.). New Delhi: Penguin.

Durba chakroborty should convert to Islam

This is so well-researched and thorough. I’m impressed.

Please stop analyzing everything with such pessimistic feminist eyes. Both female and male bodies are depicted in glorious semi naked states in the temples. You are conveniently ignoring the fact that men are also carved with semi clad beautiful bodies. We see this in Greece also. Truth be told more male nudes are found in Greece then females. It’s because a perfectly chiseled body is considered epitome of human perfection and close to divinity. Yes, the viewer gaze can objectify the body but it is also meant to strike awe and fear by beholding such glorious body in front of them.

Those are carvings on temples. There are men and women and animals and rest of the nature carved in to the temples. Please don’t cherry pick to prove your point.

The temples built 1000s of years ago has nothing to do with current social conditions..

They are supposed to be looked at, admired, both men and women statues equally.

Typical feminist garbage… such hypocrite feminist should show guts (that they lack clearly which is why they are feminist) and write something about the real patriarchy and objectification that exists in abrahminacal religions to the core