Following the fast of 68 days as a part of the Jain religious practice of ‘upwaas’, Aradhana, a 13 year old girl died in Secunderabad on 3rd October, 2016. The incident, as expected, brought to light the strict and rigorous practices followed by the Jain religion. A complaint was lodged against Aradhana’s parents for allegedly forcing her into the practice of fasting for such a long duration. Soon voices from within the community (and her family) erupted, many claiming that it was a voluntary and dutiful act on her part but the death was unfortunate. Many said that the family should be held accountable, others said that the religion or the community cannot be blamed. I was told time and again that I must stand by my religion and community, no matter what, and that I should tell people this is not what Jainism is and that these are just some bad incidents which should be forgotten.

Image Credit: NDTV

Yes, bad incidents. So we can render them insignificant and save ourselves from the discomfort of reflecting on our own religion and practices? So that we do not need to critique the ‘most peaceful religion in the world’ because most of us would never let this happen to our children?

The question is not what if it happens to our children, the question is whom does this really benefit? What power structures keep these practices thriving? The question is also not whether you should be taking blame as a community, but whether you are ready to reflect on and critique the structures and moral values that allow this kind of coercion to happen in the first place.

Understanding the Religion and the Practice of Fasting

Jain religion, popularly believed to be one of the most peaceful and difficult religions to follow in the world, essentially believes in accomplishing salvation and worshipping those who achieve it. Right knowledge, right faith, and right conduct are amongst the most essential paths in the religion, and one must observe the five vows prescribed by Jainism i.e. non-violence, truth, non-stealing, celibacy/chastity, and non-attachment/non-possession to walk on that path.

The religion is also not homogeneous or uniform in its practise and principles both. There are two sects under Jainism – Digambar and Shwetambar, and then there are smaller sub-sects within the two as well. Both of these have different belief systems. While the Digambars believe that only a human being in a man’s body can attain redemption and that a woman will have to be reborn as a man to be able to attain it, the Shwetambars believe that women can achieve salvation as women. Interestingly, nuns (sadhvis) have always largely outnumbered monks in the shwetambar sect.

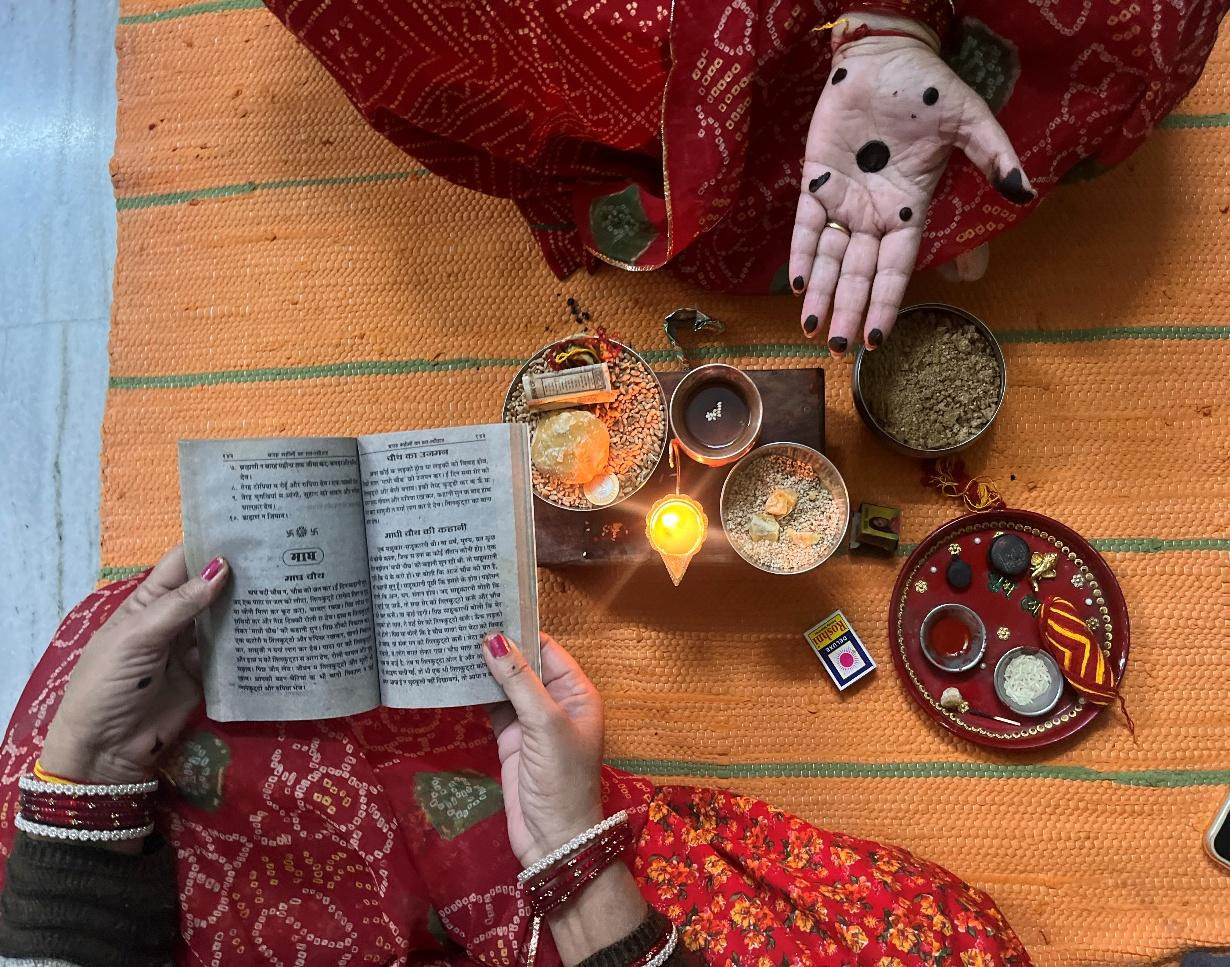

Coming to the practice of fasting – brief periods of fasting without any liquids / fluids or by restricting one’s diet over longer duration of time is considered laudable and a sign of having achieved ‘punya’ (goodness). Women / girls who are undertaking the fast give up on most of their daily activities, which are taken over by other women / men depending on the gendered nature of the task. The woman / girl spends most of her time performing other religious activities like Pooja, Samayik recitation, Shastra reading, etc. A good amount of time is spent in the vicinity of the Jain gurus, if present. The practice is a public spectacle to witness – huge processions, acts of worship, and adorning of the person with jewellery, new clothes, gifts, etc. Basically a conformation of her participation into the age old oppressive rituals of placing the man before woman, self before god, and so on. The fast then, literally becomes a public undertaking which accrues prestige for the family, and a good future (read husband) for the girl. Another way to gain some ‘punya’, if not by fasting, is by participating in the commemoration of the act, by honouring it and spending time in the service of the one who fasted.

Gender, Religion and Modernity

An interesting aspect of Jainism that cannot be left unattended is that its founding texts are all written mostly by men. Which is why, having a gender lens on questions of religion is curial in order to question the controversial practices that are upheld and celebrated under its name.

Further, talking of gender and religion reminds me of two prominent incidents within the context of Jain religion. First, Acharya Tarunsagar Maharaj’s speech in the Haryana assembly and second, Sadhvi Riddhi Shri’s elopement with a man she fell in love with. To briefly describe the incidents – Tarun Sagar Maharaj gave a speech in the Haryana state assembly passing sexist remarks on women, calling out men to keep their women under control – an analogy he made to prove why religion’s control over politics is important. The second incident is the one where Riddhi Shri, a Jain sadhvi happened to elope with a man she fell in love with, by staging a santhara, years after she was forced into taking diksha at the age of 9. One must not act naïve and assume that these are isolated incidents occurring in their own detached spaces or in a vacuum. It is necessary that we put a gender lens while critiquing practices of religion in order to highlight issues in a way that can be understood only by looking at gender as a social construct.

A lot of contemporary practices within the Jain community exemplify how religion can be performed in a ‘modern’ way. This shift has affected the non-religious practise of the community to a great extent. The shift arises from the very stereotypical binary of tradition vs modernity – wherein to ‘tackle’ modernity, the community disguises itself as modern. It is important that we challenge the meanings of traditional and modern here, especially in the context of how modernity intersects with the lived experience of a Jain lay person.

The compatibility of religion with modernity is prominently depicted in the Jain community. Case in point, the overt institutionalisation of ‘arranging marriages’ in some parts of the Jain community feed on the anxieties that come with rise in inter caste marriages within the community. This led to the forming and strengthening of some regional / national / global programs like the Yuvak Yuvati Parichay Melavas, Youth Forum for Jainis, Jain Milan Program, Rashtriya Adhiveshan, etc. I have been invited to become a part of these programs multiple times. The main agenda is to subtly encode young Jains into believing that they are given agency to ‘decide’, and ‘choose’ their life partners by means of getting to know them in these spaces. Disguised as a radical and cooperative exercise, this highly controlled and guarded platform decoys girls into believing that they can ‘choose.’ By developing self-righteousness for one’s own upper caste status, ‘superior’ religion, lifestyle, etc. such practices push certain ground rules so subtly that they are seen as essentially in favour of the girls, making them believe that these new spaces are indeed a challenge to the problems and anxieties of modernity.

It’s important to ask what passes as (good) traditional and (bad) modern, along with what gets legitimized, and indoctrinated into the minds of young girls.

The Question of Agency

When women, including young girls assert their agency through performance of religion to gain rewards of social acceptability and honour, we cannot do away with the cultural and institutional structures that manipulate her into desiring that agency. Taking up religion the way society consents, brings women the rewards of not just sisterhood but also subject-hood. I myself remember participating in fasting and other religious activities in my teen years diligently. The fact that I grew up in an environment where resistance to cultural practices brought ignominy to my family and where all of my friends indulged into the same practices that I was told to, literally trained me into believing that there is no alternative to this life. So to fit in, I kowtowed and accumulated admiration for my family’s good values.

Agency has a lot of grey areas, and it doesn’t concretize in a void. It is formed by the act of ‘observing’ – an act that allowed Aradhana to witness and create a space for articulating her constructed desires and aspirations. Observation became her reasoning to volunteer.

This is not to say that girls and women follow religion blindly, in fact, most of the women and girls have their own interpretations and they find their unique ways of performing religion. In fact, Jain monks and sadhvis are known to have an incredible capacity to fast for days and months at a stretch. Not just that, a sadhvi’s life is considered far more liberating than any laywoman, for through abstinence and temperance, they remain free from the norms of domestic labour, motherhood, wifehood, and capitalist consumerism. The idea is to teach lay women to remain as pure as possible, without having to give up on her ‘duties’ of providing sexual, emotional, and domestic labour to her family. It is not surprising that a lot of unmarried young Jain girls take the oath to remain ‘bramhacharini’ until their family finds someone to marry them off with.

What I wish to highlight here is that, what an ideal sadhvi projects is actually the desired conduct and image of Aradhana and many other young girls. Their attachment to Jain values of purity, salvation, and righteousness further get emphasised through mass ritualistic programs, listening to religious speeches (‘pravachans’), and indulging in fasting and so on.

When Aradhana’s father claimed that she chose to fast, I couldn’t help but wonder – “Aren’t all the major decisions for unmarried young girls taken by their parents, and especially fathers (extended kin in some cases)? What makes it even slightly possible for us to believe that her family could not stop her from continuing the fast or intervene into what their 13 year old girl was asking for?”

No encouragement or intervention in her choice to fast for so long does not imply that she was actively discouraged from taking such a grave step. This proves only one thing – that attached with the girl’s ‘tapasya’, comes great honour for the family. If an act like this causes social nobility for the girl’s family, then an obvious causality is any limitation on the girl’s part to perform it, for that brings great dishonour and embarrassment to the family.

To put things in perspective, look at the case of Sadhvi Riddhi Shri, who eloped a few years ago, because she fell in love with a man. On her wall calendar, the date of disappearance (elopement) was encircled in red, and the word ‘siddhi’ (liberation) scribbled alongside it. The case ended in disgrace and shame for the sadhvi who along with her lover was recovered, arrested, and boycotted for life; her family in a village in Ajmer district in Rajasthan also being held up in scandal.

So while you may not notice physical coercion, violence, or bodily force exerted by parents on young girls and boys, they are taught that not following religion brings them disgrace and grants a place in hell. The idea that gets circulated is that that there is no option but to follow the practices. This is violence in its subtlest form, and it is unacceptable.

‘Santhara’

This is another controversial practice that is followed in the religion. Santhara, or ‘Sallekhana’ is a practice wherein when all purpose of life has been served, a person can opt for death by choice – by willingly shunning life’s enticements — food, water, people, emotions; one by one. Jains claim that this act is not suicide, for suicide results from depression, anger, loneliness and Santhara is observed amid worshipping, glorification, and celebration. It is seen as a self-purification practice wherein you take death in your control. It is interesting to note that Santhara is not prescribed as an essential practice in Jainism to attain redemption, and yet its glorification and occurrence passes without any critique whatsoever.

Aradhana’s dead body and her funeral procession is a solid example of how one conveniently places a carpet over glaring questions of child rights and gendered violence, amid all the hyper-glorification of her death. It is only possible under a patriarchal set up that on the death of a young girl, over a thousand other women, including her family, instead of mourning, dance and celebrate, feeling lucky to have experienced such a special event.

In Conclusion

The participation of women in conservative religious practices, in baseless adulation of controversial practices, and utter silence over the blatant sexism clearly demonstrate that though women enjoy some amount of control over their lives, they operate within strictly regulated environments, oppressive cultures and male dominated institutions while asserting their constructed agency.

The Jain community has been, rather aggressively, marking its strong relationship with the state in recent times. Tarunsagar Maharaj’s intervention into a political space as an authoritative voice wasn’t the first time religion interfered into politics or made irrefutable claims on women’s bodies and lives. But his remarks were significant and cannot be ignored, because as a monk, he has the power to give legitimacy to what he says. So when something like what happened with Aradhana happens, it becomes possible for the community to say that no one is supposed to interfere in their religious practices.

Is it not important then, that as a collective we need to reflect on our hypocrisy and raise our voice against the injustice? Is it not necessary that we strongly oppose the self-proclaimed authoritative voices of the community who pass judgements on how women and girls should conduct themselves?

I am calling for a structural critique of the religious ethos and the continuing practices of the Jain community, for they seep into the everyday lives of women who are oppressed and coerced into performing religious and cultural practices that only feed the morality and vested interests of a patriarchal religious institution.

Featured Image Credit: NPR

About the author(s)

Nupur is a graduate in Women’s Studies. Interests include research, academia, gender, sexuality and politics.

Nupur, you have nailed and identified the subtle evils of the so-called rich ( by culture ) Jain community. The one kind of violence that you have identified is pretty much in vogue still across sections of all Jain sects and societies. Its a very patriarchal base there, and no women has the right to question. Jain women are pressured, and lead a taxing life. I have defied a few and so am a Rebel more by the women folks.

The Aradhana case here may not have feminist angle as such, but its a fact that since Girls are brought up with more inhibition could probably true too. Being a Jain myself, have seen people around me fast for about max 30 days, this 68 days sounds so very extreme.

I had interrupted my mothers fast after 7 days by adopting hunger strike of the remaining family, while she wanted to continue upto 10 days for the paryushan parva.

Am branded what not for that deed of mine, by all my relatives, my mother understood me though.

Its normal sight for all others but my heart bleeds when I see relatives all around fasting for more than a day. Scientifically, single day fast alone is healthy beyond which is senseless.