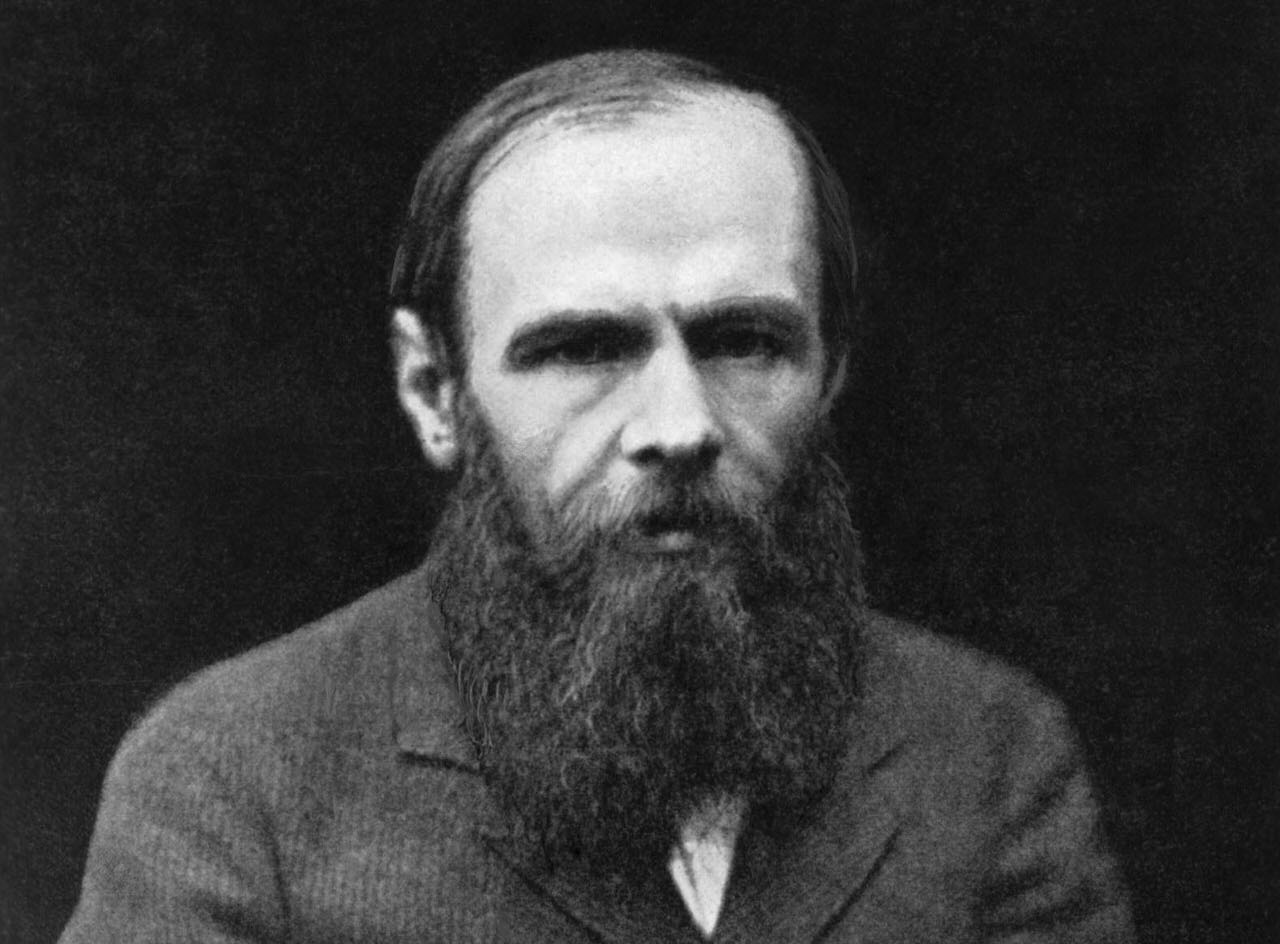

Today is the birthday of one of Russia’s greatest writers, Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose books have graced my shelves since as a school student I picked up one of his works, The Insulted and Humiliated (1869), a novel with detailed sketches of characters I related with and in whom I saw reflections of people around me.

Most of Dostoevsky’s female characters, including Natasha from The Insulted and Humiliated, show a great deal of fortitude at the face of difficulties. Yet they are not one-dimensional as they grapple with inner conflicts and play them out in their exchanges with other people.

In The Insulted and Humiliated, Natasha leaves her parents to stay with a man they will not accept and later has to bear the brunt of his irresponsible actions. She finally tells him to leave her when she finds out he is confused between her and another woman. I found Natasha striking because her empathy for the people around her, even for the man with him she runs away with and who later deserts her, is never lost. Also, just like she is not afraid to act upon her emotions despite social strictures, she takes decisions on behalf of the man-child (Prince Alexey) she loves, no matter how grave the emotional toil of it. Natasha is in control of her life, taking decisions and standing by principles she believes in.

This brings me to one of Dostoevsky’s earliest novels, Netochka Nezvonova (1849), in which the trope of a child orphan is worked upon. It is an unfinished work which shows Netochka grow over the years from a girl-child infatuated with her father and stealing money from her mother for his drinking adventures to a woman who realizes the unfairness of the treatment meted out to her mother. Netochka’s mother is called a ‘dreamer’ who marries an aspiring violinist she is enamored with only to discover that he tells friends and acquaintances that she is “a peasant, a cook, a coarse, uneducated woman.” He blames her and their domestic life for ‘destroying’ his talent in music to hide his own insecurities and mediocrity. Meanwhile, Netochka’s mother supports the family till she dies. This situation is very potent even in this century when women’s household chores are often looked down upon though they sustain the family.

Netochka grows up seeing her parents fight and she keeps siding with her father to win his favour as she fails to grasp the economic situation of the family. She is consumed by the compassion she feels towards him and the fear she has of her mother’s authority. Yet, she does feel her mother’s misery at times when it spills out in the open. Dostoevsky paints a layered picture of Netochka’s childhood where she feels compelled to choose between her father and her mother, a difficult situation for someone so young. Netochka’s infatuation with her father has a rude awakening only when he decides to abandon her after her mother’s death.

As a protagonist, the older Netochka has a deep insight about her own psyche. She assesses herself as “by nature infinitely long-suffering” and “an outburst or any sudden manifestation of emotion occurs only in a crisis” – a reflection on how she seeks to retain composure in the gloom. In a similar way, she is good at reading people and forms deep bonds with the people around her. Dostoevsky describes her raging love for Katya, the girl-child of the family who adopts her, very vividly as they kiss each other “almost to pieces.” Netochka is the embodiment of the bright, ambitious woman, seeking out books from libraries and joining music classes after finding out that she can sing well. Unlike her father, her talent is not an illusion sustained on an inflated ego.

About the author(s)

A journalist by profession, I love reading and finding out about different countries, cultures and people.