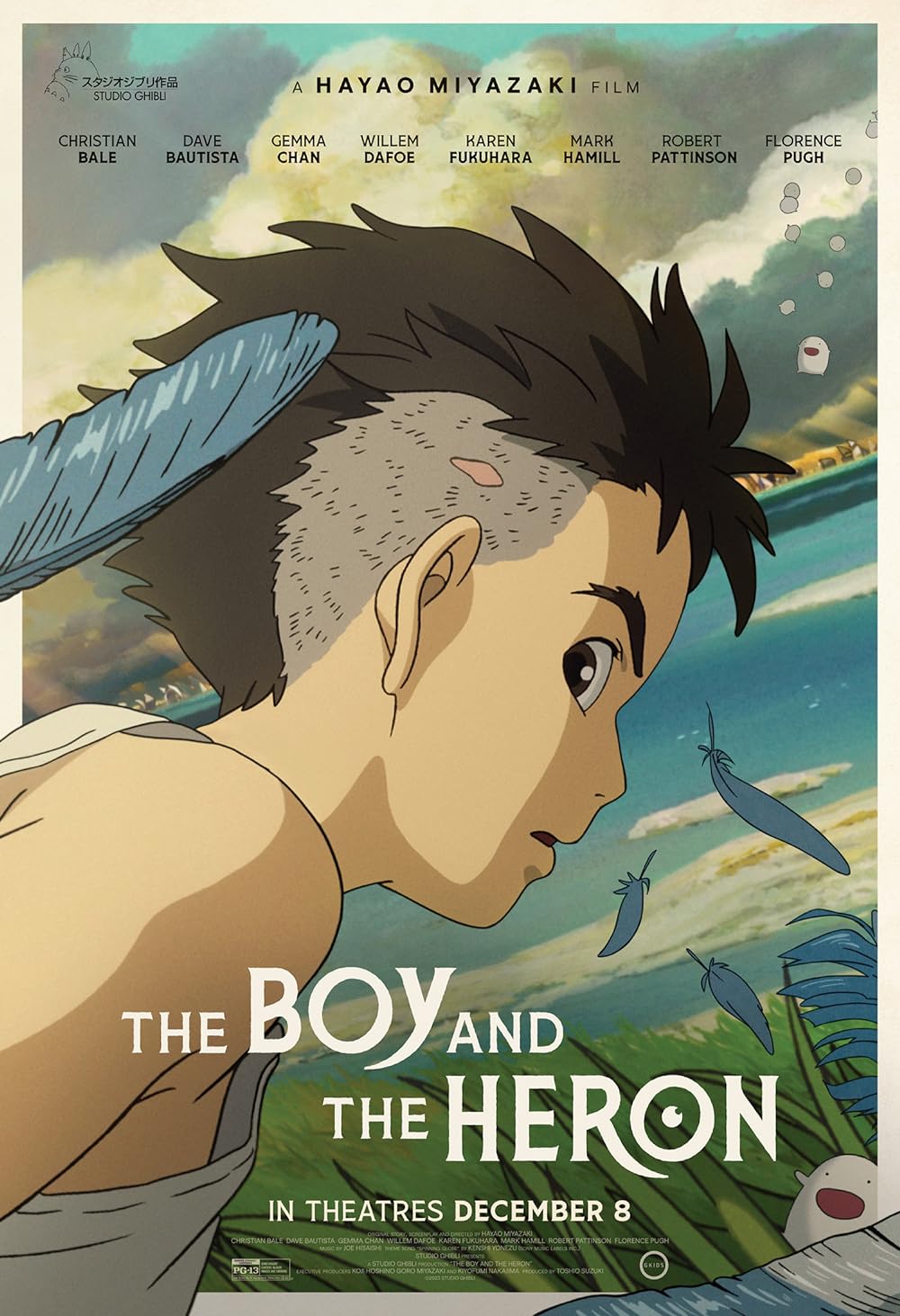

The first Ghibli film to be released in Indian theatres, The Boy and the Heron is a dream that one must enter to experience the magic of Miyazaki, Suzuki, and Takahata’s legacy. Devastatingly personal, whimsical and surprisingly dark, Miyazaki’s latest offering sweeps you into a child’s world – albeit disturbed, and sails you to an old man’s island of worries and nostalgia.

The central plot of The Boy and the Heron begins with Mahito relocating to the countryside with his father, who is set to marry Mahito’s mother’s sister – Natsuko.

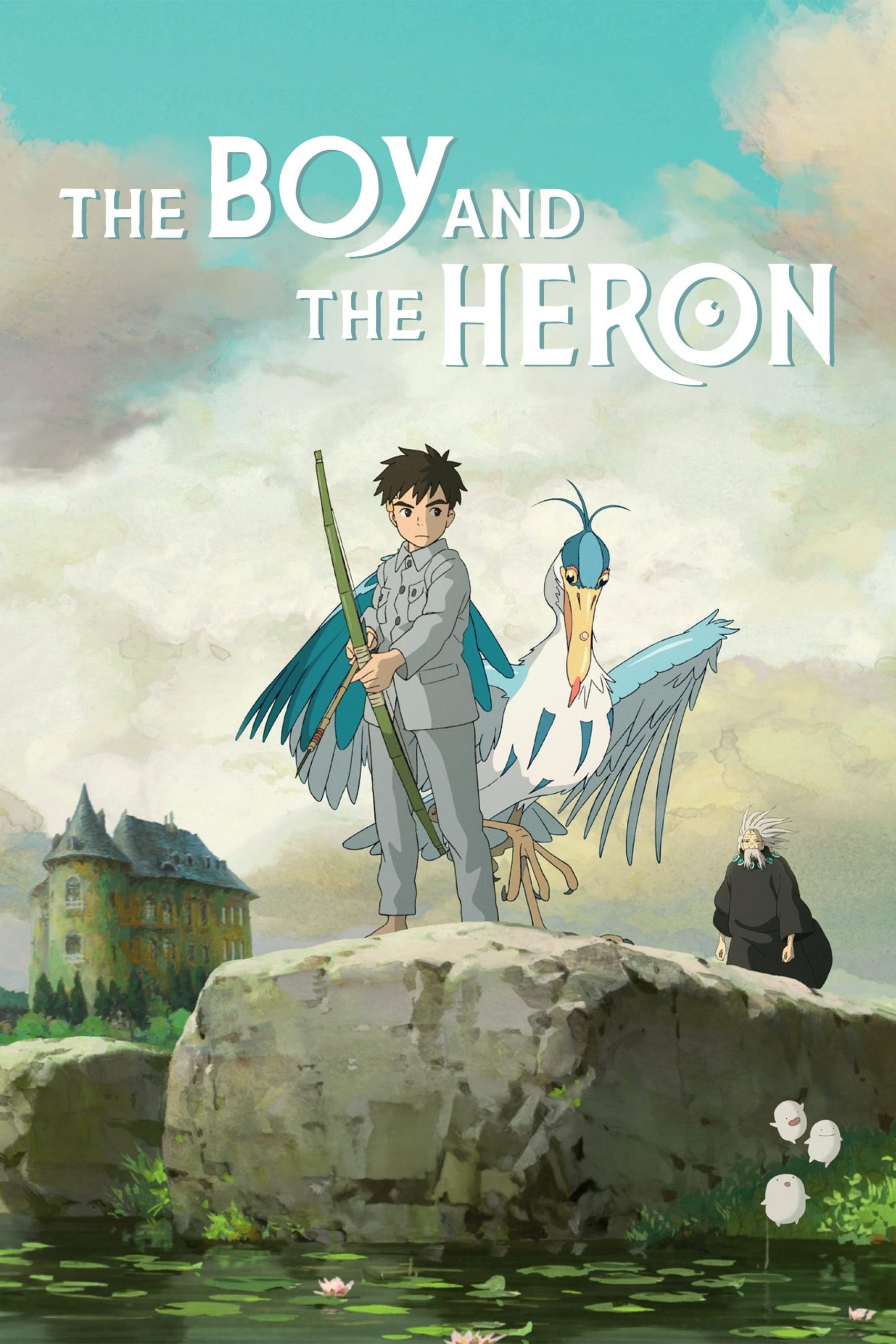

The story is set in 1940s World War II Japan where our protagonist Mahito loses his mother to a Tokyo bombing. The central plot of The Boy and the Heron begins with Mahito relocating to the countryside with his father, who is set to marry Mahito’s mother’s sister – Natsuko. The signature landscapes greet you as Mahito travels to his new home. Relocation in Ghibli films signals fantastic adventures ahead, and The Boy and the Heron does not stray from this expectation. The new home is inhabited by a horde of old crones and an impertinent Grey Heron. This is the most surprising creation in the film – as the Grey Heron soon morphs into a grotesque goblin-like creature.

Rarely do Miyazaki’s villains or grey characters appear to be ugly. From Yubaba (Spirited Away) to Nago (Princess Mononoke) to the Witch of the Waste (Howl’s Moving Castle) – none of the characters embodied the uncanny in the way the Heron does. The Heron leads a curious and grieving Mahito to the abandoned and forbidden tower, that was partially collapsed. And as we know, by Ghibli-logic, any abandoned eerie structure means an adventure. The tower indeed reveals itself as a portal and the madness of Miyazaki’s magic begins thereon and rarely takes a breath through the film.

The entire action of The Boy and the Heron is concentrated in this netherworld that exists within or beyond the tower. Mahito traverses the world, aided by Kiriko – a sailor and fisherwoman and Lady Himi – the fire-wielding saviour, to find the lost Natsuko, and inadvertently face the grief of losing his mother. As Miyazaki continues to refuse the three-act narrative of Western concentration bandwidth, this film veers even further away from a structured plot. This entire world of man-eating parakeets, ghoulish pelicans, fire-wielding saviours, gentle wispy creatures who float into the real world to be born as new life – is tethered to a few building blocks precariously arranged on a table, overseen by the lord of this kingdom.

‘The animator must fabricate a lie that seems so real viewers will think the world depicted might possibly exist’

The film presents itself as both a child’s imagination as well as an octagenarian’s lament. Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel How Do You Live?, published in 1937, impacted Miyazaki in his growing years. Both the book and the film are designed as a coming-of-age story of a boy, looking for the meaning of life. The Boy and the Heron is deeply autobiographical and personal – especially in the questions about life and its philosophy. Mahito’s father also works in an aeroplane manufacturing factory, just like his own. Similar to a lot of mothers in Miyazaki’s films, Mahito’s mother is also sick and hospitalised – reflecting his own mother’s time spent in hospital wards during his childhood. Relocation, again a leith motif in his films, is inspired by his childhood migration.

But beyond the surface, this film is autobiographical on a philosophical scope. In a crucial moment of the film Mahito stands at the doorway that can lead him into the real world, an escape from the netherworld of the tower. Before choosing to stay back in the tower he says, ‘I know it’s a lie, but I have to see.’ This lie and this urge to explore more seemed at once the voice of the character and the echo of Miyazaki’s mind. The lie reminds one of Miyazaki’s reflections on animation in the 1979 book Starting Point ‘The animator must fabricate a lie that seems so real viewers will think the world depicted might possibly exist.’

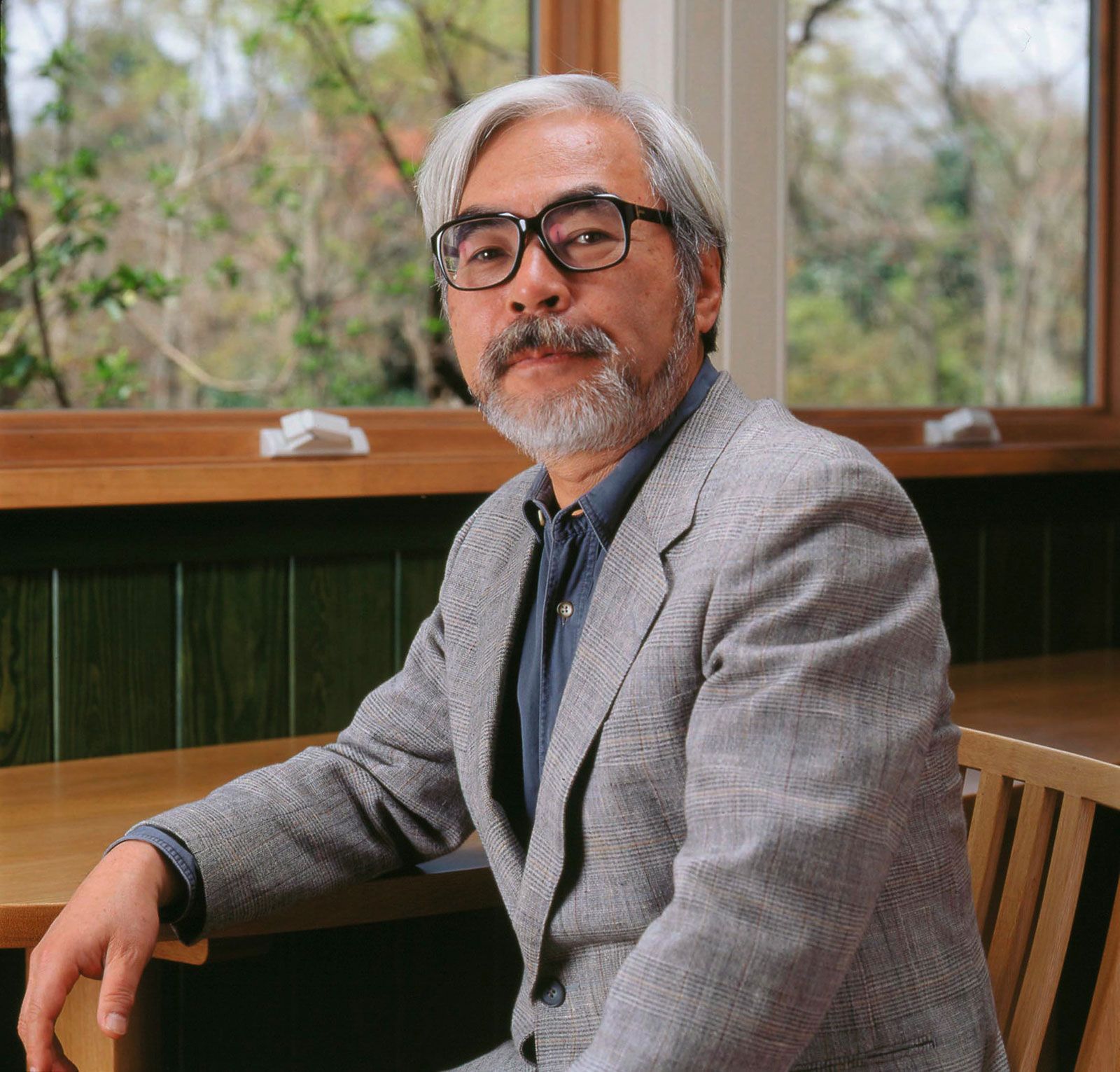

This lying is extended by the Heron’s constant deception. The world and its guide are both unreliable and fickle. Yet one must know more, see more and in Miyazaki’s case create more – as he continues to suspend his retirement. Right after the release of Princess Mononoke, in 1997, Hayao Miyazaki announced his plans to retire, in 2001 after the release of Spirited Away he announced his retirement, and after the release of The Wind Rises he announced again that he was retiring in 2013. And here we are, discussing his latest release in 2024.

Miyazaki’s pain with this world is not unknown. In a famous interview from 2013, he is heard saying, ‘If you really think about it, is this not just some grand hobby? Maybe there was a time when you could make films that mattered. But now? Most of our world is rubbish.’ His disenchantment with the world of animation and defeat in seeing a future for Studio Ghibli seems to be reflected through the king of the tower’s fantastical world.

Halfway into The Boy and the Heron we meet the great-grand-uncle of Mahito. He is the one who lured him into the tower and wants to hand over this world to a worthy successor. He struggles to find one, even in Mahito. He implores Mahito to take his place at the table, arrange the building blocks that hold this world together, and rearrange them every few days to keep the world fresh and intact. Mahito refuses to touch the tarnished blocks and soon after, the netherworld starts falling apart.

The true abundance of Ghibli’s hand-drawn animation strikes you when witnessed at that scale.

In 2023, Studio Ghibli was finally sold to Nippon, unable to find a successor after Hayao Miyazaki. Goro, Miyazaki’s son, was approached with the position but he repeatedly declined the idea as he did not want to lead the studio alone. In the 2013 interview, upon being asked about the future of the studio Miyazaki said on a fatalistic note, ‘The future is clear, it’s going to fall apart. I can already see it.’

The Boy and the Heron pays homage to all our Ghibli favourites

It might take a few business days to wake up from the experience of watching The Boy and the Heron on the big screen. The true abundance of Ghibli’s hand-drawn animation strikes you when witnessed at that scale. The film uses dream logic, taking you from one space to another in lucid turns.

While the world within the tower draws you in with spectacular visual finesse, this is also where the film stumbles at its pacing and narration. The second half of The Boy and the Heron skips from one setting to another in quick disorienting steps. The great-grand-uncle declares the need for succession without much ceremony and his interaction with Mahito feels abrupt.

In parts, the film seems to be missing pieces. This is unlike most other Miyazaki films which despite creating wild and vivid worlds of imaginary creatures can tie stories back neatly before returning the audience to reality.

The Boy and the Heron’s nostalgia for its legacy is also evident through the two hours of its running time. You will meet homages from many Ghibli favourites – a version of the Shikigami from Spirited Away, a variation on the Kodama from Princess Mononoke, the fireplace from Howl’s Moving Castle, and many other small and big references.

The opening fire sequence will remind the audience of Isao Takahata’s heartbreaking masterpiece Grave of the Fireflies while the dynamic blurring lines might bring back memories of Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya’s incredible running sequence.

The opening fire sequence will remind the audience of Isao Takahata’s heartbreaking masterpiece Grave of the Fireflies while the dynamic blurring lines might bring back memories of Takahata’s The Tale of Princess Kaguya’s incredible running sequence. Without references, this film might be overwhelming for a first-time spectator to make sense of this world due to the sheer volume of characters.

The Boy and the Heron is also darker than expected. The Grey Heron’s uncanny appearance is not the only disturbing presence. Miyazaki’s preoccupation with flight morphs into a rather complicated relationship with birds in The Boy and the Heron. His work has generally dissuaded from anthropomorphism, ensuring the boundaries between humans and animals are not blurred. No animal really takes on the behaviour or characteristics of humans. Even though the cat speaks to the witch in Kiki’s Delivery Service or the curse turns a human head into a pig’s in Porco Rosso – we do not see the Pixar and Disney-like anthropomorphism in his work, until now.

The man-eating parakeets are jarring in their human-like behaviour and garbs – ready with their cutlery to eat Mahito. The pelicans of the netherworld that eat the kind and gentle Warawaras add to the darkness of the world. As the wispy creatures float in moonlight to be born in the other world the pelicans swoop in, to gulp them down. In a second the wistful sequence turns gory as the pelicans are burnt by Lady Himi to protect the Warawaras.

In the middle of the overwhelming darkness, there are moments of Miyazaki’s signature humour. Once released from the tower the giant parakeets shrink into their natural size and almost immediately start splattering their droppings over all the characters. In a hilarious moment, Mahito’s father shrieks that Mahito has turned into a bird, mistaking the gushing parakeets from the mouth of the tower to be his son.

Previously speculated to be the last piece by Hayao Miyazaki before retirement, The Boy and the Heron is a testament to his mastery and imagination.

Previously speculated to be the last piece by Hayao Miyazaki before retirement, The Boy and the Heron is a testament to his mastery and imagination. We shall always hope that Mahito chooses not to close the door into the tower of impossible creatures and wild stories – and we get to watch another Miyazaki classic, soon.

About the author(s)

She/they is an editor and illustrator from the suburbs of Bengal. A student of literature and cinema, Sohini primarily looks at the world through the political lens of gender. They uprooted herself from their hometown to work for a livelihood, but has always returned to her roots for their most honest and intimate expressions. She finds it difficult to locate themself in the heteronormative matrix and self-admittedly continues to hang in limbo