Long before I knew what feminism meant, I knew what it was like to be watched. I realised that there was an insatiable, pervading eye fixated on all women. It delineates the good and the bad, dictates the moral configurations a girl must embody, and solidifies our deepest convictions. The strange thing about such surveillance is that it soon turns inward, making you a voyeur of yourself.

Nearly all of my teenage years were spent in a performance of what I believed was most desirable. At all times, I felt like I was inspected through a keyhole, often one I had constructed inside my head. Before Judith Butler appeared in our textbooks, we were passing lip glosses under our desks. The Ideal Woman came at the cost of perceived feminine perfection.

For most of my growing up, I was made to understand feminism as unwelcome activism. It had mutated into a pejorative pelted at girls who dared to show discomfort. The feminichi (a popular derogatory slang term for feminists in Kerala), was very much placed outside of societal standards of acceptability. No one wanted to be her. The unapologetically angry girl was often casually paralleled to mythical rakshasis, their emotions compared to vile monstrosities. There was born a simultaneous need to be liked and make ourselves palatable visions of a rom-com fantasy. So when I first really understood feminism as a movement, I struggled to jointly hold and reconcile my seemingly conflicting feelings of anger and helplessness.

In Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, she described women forced to find meaning within the peripheries of their nuclear families. They would consume tranquillisers throughout the day to dull their emotions and frustrations. This was the plight of homemakers six decades ago. However, even now, not a lot has changed. Understanding feminism is never a flashpoint that promises acute clarity. There is much to unlearn and also to relearn.

At fourteen, when I resisted harassment on a public bus, I was scornfully asked if I were a feminist. More often than not, it is a thing of shame to assert autonomy. Modern and liberated women leading successful career lives are still labelled as “crazy bitches” for expressing their opinions. In this light, popular filmmaker Aashiq Abu has redefined feminichi as a “title conferred to any woman who has an opinion.” Actresses and activists continue to increasingly embrace such connotative, linguistic restyling of feminist identities in attempts to widen the visibility of the damaging rhetoric that has percolated into the language of every day.

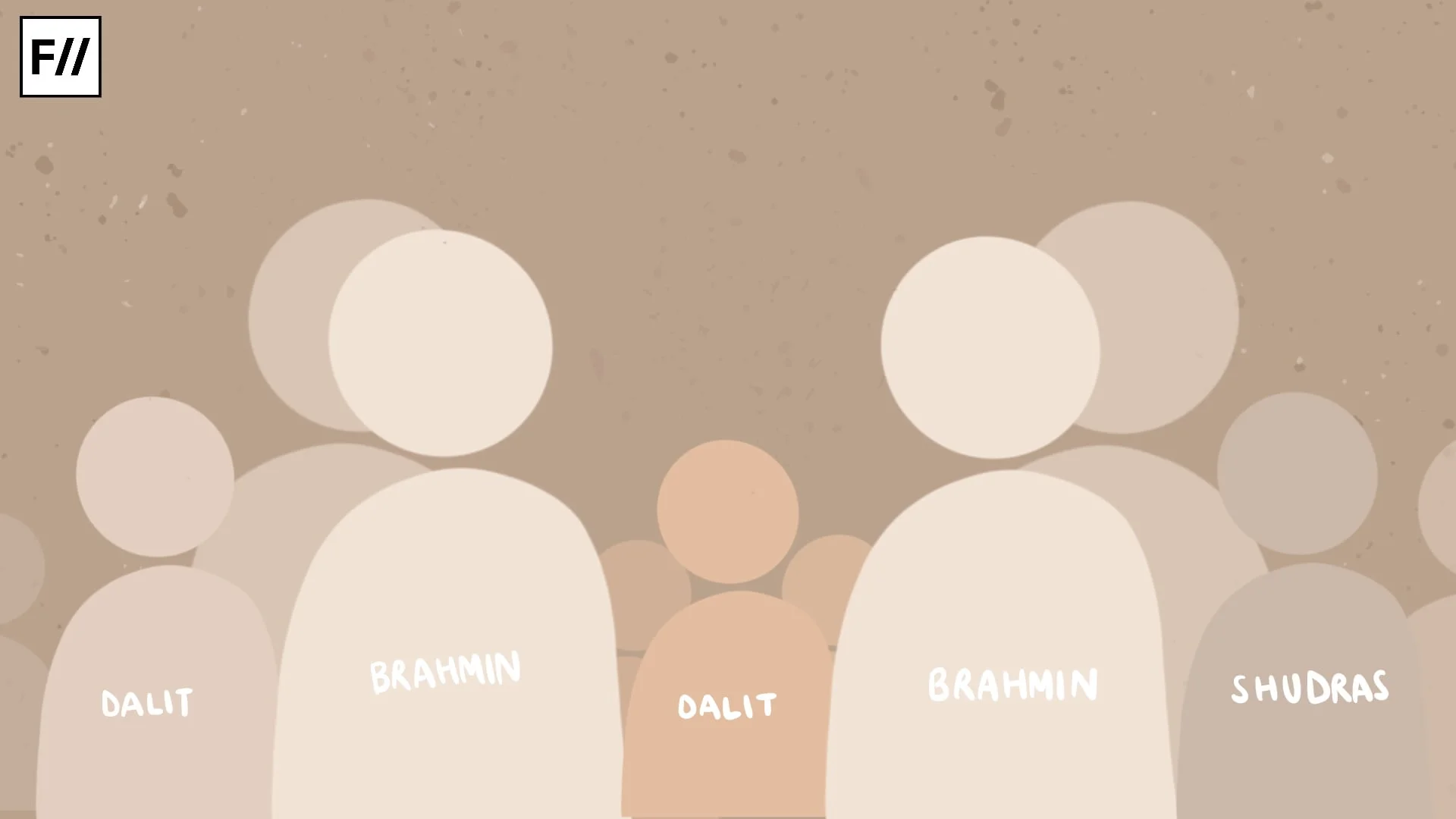

At the epicentre of feminist discourse is an unbridled fury. In a world governed by patriarchal tenets, harnessing that anger is portrayed as some sort of cosmic, clerical error. Frequently, women are relegated to small corners as we witness everything begin elsewhere, far out of our yearning reach. Today, as our country erupts in protests against the heinous crimes perpetuated on women, our unceasing understanding of injustice is amplified by a growing awareness of systemic injustices.

This year we have been daily observers of genocide and wars. Every day is spent in a frantic scanning of the news, watching worlds burn at a distance. The feeling of such a staggering loss is always accompanied by disappointments in the failing values of feminism. As we watch mothers bury their children, girls denied their right to education and access to opportunities, and women struggle for basic human dignity, it becomes painfully clear how far we still are from the ideals we strive for.

The devastation is not just in the images of conflict but in the realisation that the hard-won rights and protections for women and girls are among the first casualties of these crises. Feminism, which promises equality and justice, seems to falter in the face of such overwhelming violence and oppression. Here, we collectively navigate a terrain of dissonance and disillusionment. The only weapon we can wield appears to be the very same uncharted rage we were discouraged from feeling all our lives.

As heavy layers of social conditioning are shed, what emerges is an unnerving fact that the world as we know it is built on foundations that actively work against us. It is a revelation that is equally isolating as it is infuriating. This knowledge carries with it waves of unrest. Every woman I talk to shoulders this profound weight. It is the burden of seeing the world not as it is, but as what it could be.

In the end, the struggle for feminist liberation is as much about looking into ourselves as it is about the external fight. It’s about learning to trust our voices, embrace all of our feelings of great disappointments, and channel them into glorious action. It’s about recognising that the fight for equality is not just today’s battle. As we stretch toward a compassionate and inclusive future, we carry forward the hope that sustains it.

About the author(s)

Gayathri S (she/her) is currently pursuing her master's in English. With a deep-rooted love for literature and writing, she hopes to streamline her interests towards a career in journalism. Alongside her studies, Gayathri has gained practical experience through internships in content writing, editing, and research. These opportunities have strengthened her commitment to impactful storytelling and managing projects aligned with broader social goals. Gayathri looks forward to merging her passion for writing with journalism, where she can explore and report on diverse narratives.