According to Joan Acker, the term “gendered institutions” stands for the idea that ‘gender is present in the processes, practices, images and ideologies, and the distributions of power in the various sectors of social life.’ (Acker, J., 1992, p- 567). According to her, almost all institutions conceivable are gendered with cis-heterosexual males being privileged above all other gendered bodies and identities.

According to her, almost all institutions conceivable are gendered with cis-heterosexual males being privileged above all other gendered bodies and identities.

Often spaces that on the surface are framed as liberating or neutral are also covertly gendered. One such institution in the present context is social media. The Cambridge Dictionary defines social media as websites and computer programs that allow people to communicate and share information on the internet using a computer or mobile phone. Moosa (2021) notes, ‘there is no denying that our days are incomplete without these sites.’ Their growing popularity owes to the fact that they are cost effective, easily accessible, flexible and dynamic, allow easy communication, and let people produce and share creative projects.

One of the fastest growing social networking sites is Instagram. It is a free photo and video sharing social networking service founded by Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger in 2010 and currently owned by Meta Platforms Inc.

Instagram’s ambiguous stance on gender identity

Instagram’s relation with gender is dualistic. On one hand it can be seen as a tool for liberation and gender equality and on the other as a mechanism for subtly maintaining and perpetuating age-old biases and stigma. While it has allowed visibility to many gender identities outside the traditional binary and has allowed those who do not fit the gender(ed) expectations of the society to find a voice and a virtual community to interact with, it has also been a tool for subtly perpetuating traditional gender norms and stereotypes.

Marketing strategy and gender stereotyping

According to Vilaronga et al. (2021), Social media platforms employ inferential analytics methods to guess user preferences and may include sensitive attributes such as race, gender, sexual orientation, and political opinions. While these can help in more efficient marketing practices, they can also perpetuate biases.

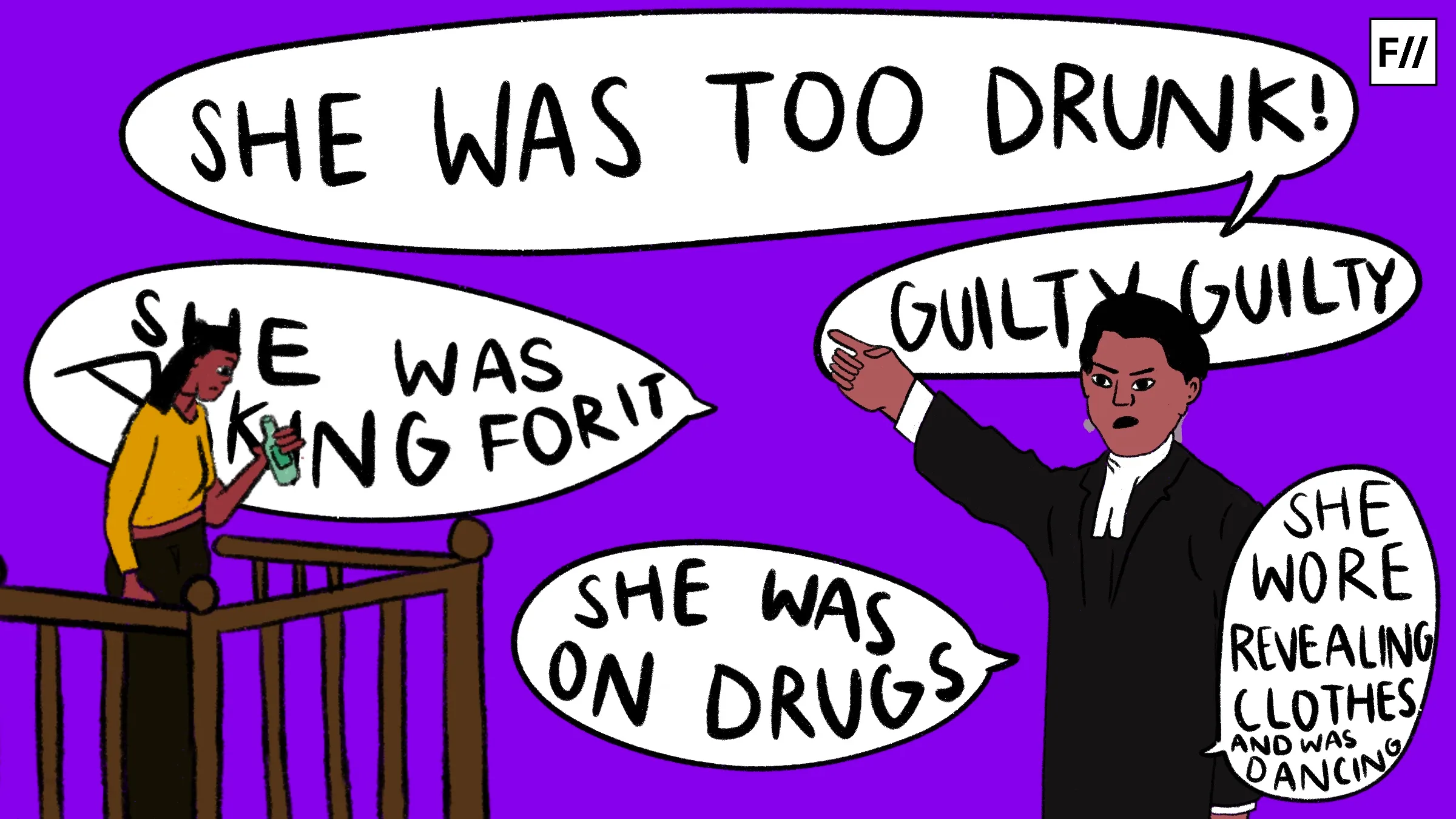

A recurrent bias is gender stereotyping. Gender stereotyping refers to the practice of ascribing to an individual ‘woman’ or ‘man’ specific attributes, characteristics, or roles by reason only of their membership in the social group of ‘women’ or ‘men’. Online platforms like Instagram often fail to grasp the subtle nuances attached to extremely complex phenomena like gender and often end up perpetuating stereotypes attached to the binary division of the sexes.

Even while there is an option for not disclosing one’s gender during the ‘sign-up’ process, the app itself infers on one’s gender identity from the patterns one follows in their social media use.

Even while there is an option for not disclosing one’s gender during the ‘sign-up’ process, the app itself infers on one’s gender identity from the patterns one follows in their social media use. And here one might ask what the basis of such judgements could be if not existing gender stereotypes?

The lack of diversity in marketing strategies becomes quite apparent when users can be gendered as male or female only. While companies may defend these strategies in the name of allowing for better consumer identification, they cannot however deny that these algorithms are inherently based on the idea that certain people are supposed to purchase certain specific things.

The ‘sign-up’ process

In the Instagram ‘sign-up’ process, as a part of one’s personal information, one is asked to specify their gender. Here, three options are given- 1. Male 2. Female 3. Prefer not to say. While the third option at first glance might seem to be progressive and gender neutral, the fact that it is placed in opposition to the other two, shows that there is a lumping together of anybody but the cis gendered heterosexual body into one category.

A very subtle but clear hint is presented that except for the cis hetero being, all other identities are those which cannot be openly spoken about, hence “prefer not to say“. This shows an inherent gender bias rooted within the very structure of the app and the imaginations of those behind it.

Online surveillance of gendered bodies

Melinda Sebastian (2019) notes how Instagram’s surveillance features function differently for different genders and bodies. In her article, she writes that when it comes to community guidelines violation, Instagram often is swift to punish anything that violates its nudity policy even when it is something that is consensually put up by women but is rather slow to take any such action when these are non-consensual and do not give women agency.

Hattie Garlick (2020) argues that often the gender roles women are expected to play in their real lives, are also translated to their reel lives on Instagram.

Here, she takes up the case of the ‘upskirt’ hashtag being allowed to stay on Instagram even though it is expressly against their guidelines but not allowing female nipples to be shown in photographs, even when posted with active agency. The hypocrisy also becomes more transparent when we look at how even after changing its policy regarding breastfeeding pictures in 2015, it did not stop censoring and blocking pictures of a popular photographer nursing her child, showing clearly that not only the marginal, but even female bodies possessing social credibility and status cannot save themselves from this scrutiny.

The app also shows a clear bias when it comes to male nudity. While Instagram is swift to censor photographs of female nipples and artists often have to adopt various creative ways (ranging from black bars to glitter to spatula!) to cover them, it does not show any hesitation, let alone reluctance, in allowing male nipples to be on full display (Jacobs, 2019). All these show a clear perpetuation of existing ideas of gender norms and morality through the platform.

Content and perpetuation of gender norms

Hattie Garlick (2020) argues that often the gender roles women are expected to play in their real lives, are also translated to their reel lives on Instagram. This happens through a policing of the kind of content women are expected to put up. In the pre-digital era women were usually expected to keep a track of the family photo album, it seems this expectation is retained even in the digital world.

Women now are often expected to put up more personal photographs of their private lives (albeit always making sure they are ‘Instagram-worthy’) while men are allowed and even encouraged to post things unrelated to their personal lives, especially those related to their work or hobbies.

It is seen that to gain popularity in Instagram, it is essential for women to conform to traditional prescriptions of femininity. While influencers may chant mantras such as ‘follow your dreams‘, but in practice, ‘If you’re trying to make a living in this space, you’re going to follow the dollars and the dollars tend to essentialize gender differences,’ says Duffy, an associate professor of communication at Cornell University. ‘The companies that tend to reach out to [female influencers] are in fashion and beauty. The brands more likely to reach out to men are based in tech and sports.‘ (Garlick, 2020).

While social media, particularly Instagram, may be a liberating platform to some and might grant visibility to gender minorities, it is inherently gendered and often perpetuates problematic stereotypes and biases regarding ideas of gender and sexuality and follows traditional moral sanctions to hold these up. Starting from the ‘Sign Up’ to what gains popularity to what even is allowed to exist as ‘permissible content’, all carry within them a whiff of normative expectations and punitive measures for the deviant.

While these slight hints may not necessarily be visible all the while, they most definitely are present. While acting as a space that is open, egalitarian, and easily accessible to all, it covertly holds up biases and stereotypes. What is required today is a closer, critical look at the most common mundane processes and then a creative reimagining and restructuring of the same upholding equity, dignity and freedom.

References:

Acker, J. (1992). From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions. Contemporary Sociology, 21 (5), 565-569.

Garlick, H. (2020, March 13). Why Gender Stereotypes are Perpetuated on Instagram? Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/2cc5ca3a-6337-11ea-a6cd df28cc3c6a68

Jacobs, J. (2019, November 22). Will Instagram Ever ‘Free the Nipple’? The New York Times.

Moosa, H. (2021, January 6). Importance of Social Media in our Lives. IIMskills. https://iimskills.com/importance-of-social-media-in-our-lives/

Sebastian, M. (2019). Instagram and Gendered Surveillance: Ways of Seeing the Hashtag. Surveillance & Society, 17(1/2), 40-45.

Villaronga, E. F., Poulsen, A., Soraa, R. A., & Custers, B. (2021). Gendering Algorithms in Social Media. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter. https://doi.org/10.1145/3468507.3468512.

About the author(s)

Shrestha Bandopadhyay is a researcher, writer, and trained sociologist with expertise in feminist theory, critical policy analysis, and community-based research. Her work focuses on marginalized communities, gender dynamics, and digital media, and she has published in respected journals. Shrestha holds an MA in Women’s Studies from Tata Institute of Social Sciences and a BA in Sociology from St. Xavier’s College, Kolkata. She is also an accomplished Bharatanatyam and Manipuri dancer. Connect with her on LinkedIn, Instagram, and Facebook.