In 2021, Statista reported that 78 percent of female respondents had read or listened to at least one book in the previous month, compared to 73 percent of male respondents. Additionally, the American Bookseller Association and Book Industry Study Group concluded that women’s fiction comprises at least 40 percent of adult popular fiction sold in the United States. How, then, did we end up considering women’s fiction inferior to other genres?

While classics can seem daunting at first, contemporary fiction, based on the world we live in now and with realistic, imperfect female protagonists, provides respite to the young reader starting out on their reading journey. More specifically, contemporary fiction, which is the literature version of chick flicks—chick lit. The word “chick” was slang used to refer to young women, even though it has a patronising connotation and ends up infantilising women. The genre written by women and for women eventually came to be known as chick lit. The fact remains that the nomenclature of the genre can be misleading, and because it constitutes a significant portion of women’s fiction, it trivialises women’s literature.

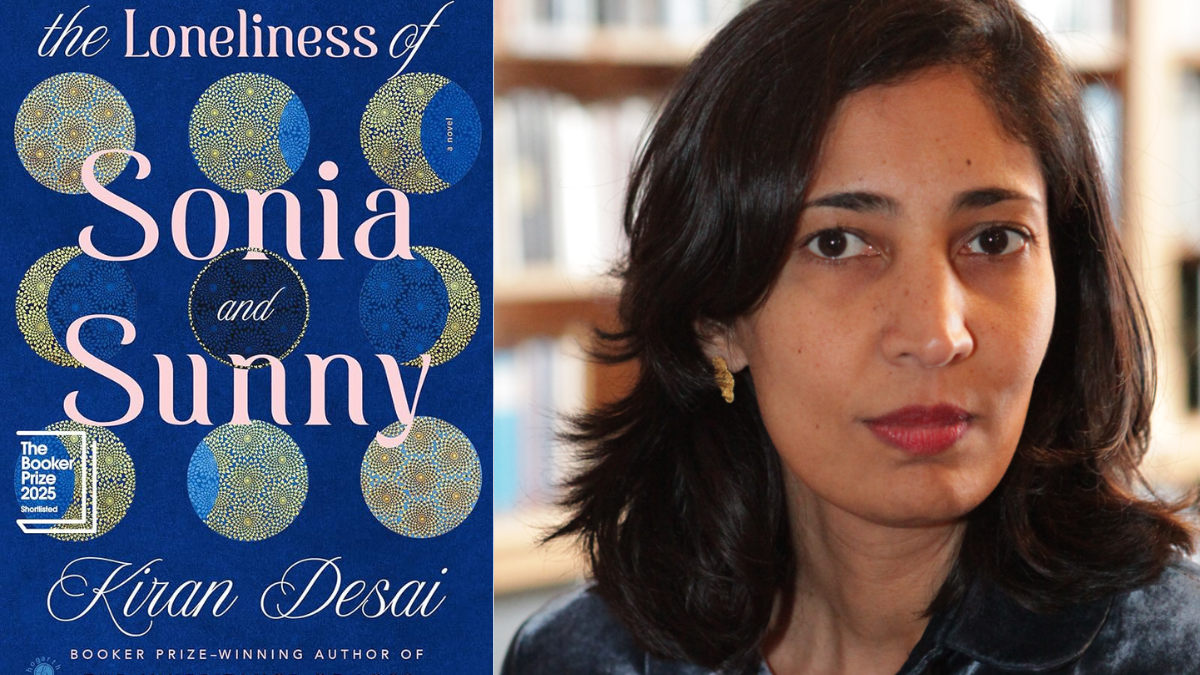

According to the Women’s Fiction Writers Association, “the driving force of women’s fiction is the protagonist’s journey toward a more fulfilled self.” This hence means that women’s fiction can be written by a man and read by men as well. Why then did we feel the need to make it into a separate genre and further trivialise it into merely chick lit? Chick-lit, romance, and women’s fiction are often used interchangeably due to the notion that they can be shallow and unambiguous to the extent that they are not seen as literary or “serious” enough. They are believed to idealise and romanticise excessively without having nuance.

Meghan Hall, lecturer and associate director for graduate studies in the Department of English at the University of Pennsylvania, noted that “‘Chick lit’ was a name given to fiction that emerged and thrived from roughly the 1990s to the early 2000s, originally in Britain and the U.S. These were books written mainly by women and marketed to young women in their 20s and 30s. The protagonists were similarly young, kind of plucky, often imperfect or a bit awkward, almost always living in a city or an urban environment and seeking fulfilment, whether through a romantic connection or professional development or finding meaning in their lives. Think Sex in the City, think Bridget Jones’s Diary.“

Undermining chick lit

Following its widespread popularity in the 1990s, it became commonplace to label the genre of light-hearted fiction novels authored by women as “chick lit” without fully understanding the underlying reasons. It is about the etymology of the genre, wherein fiction by women and for women must be chick lit and is not broadly referred to as women’s fiction. Putting the works of women under the umbrella of romance and chick lit trivialises women writers’ works at large.

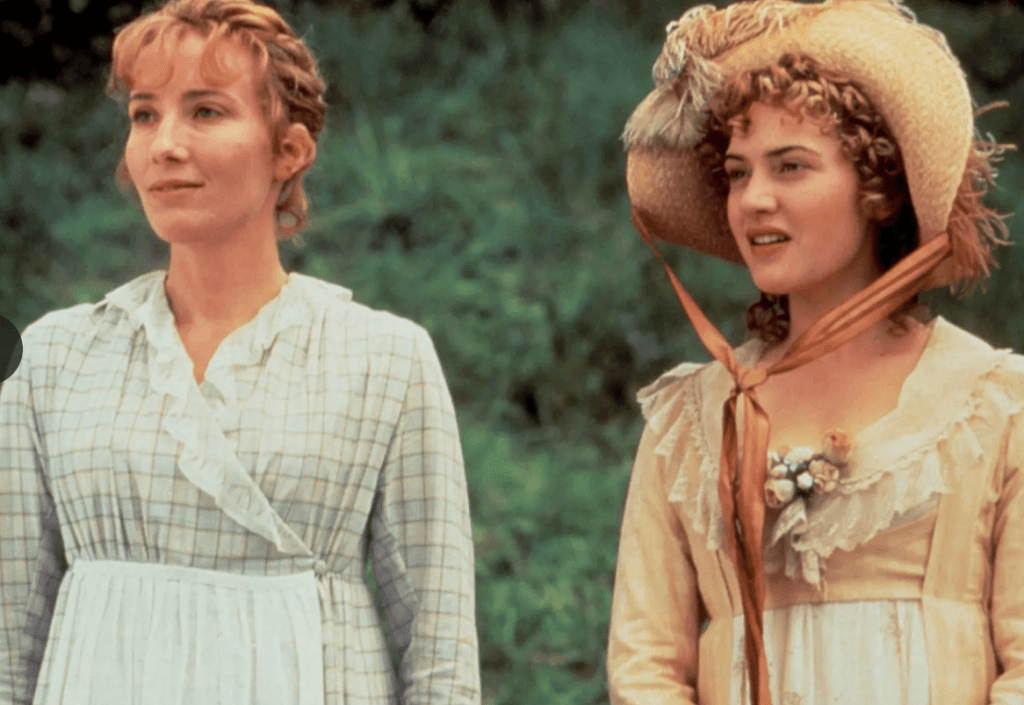

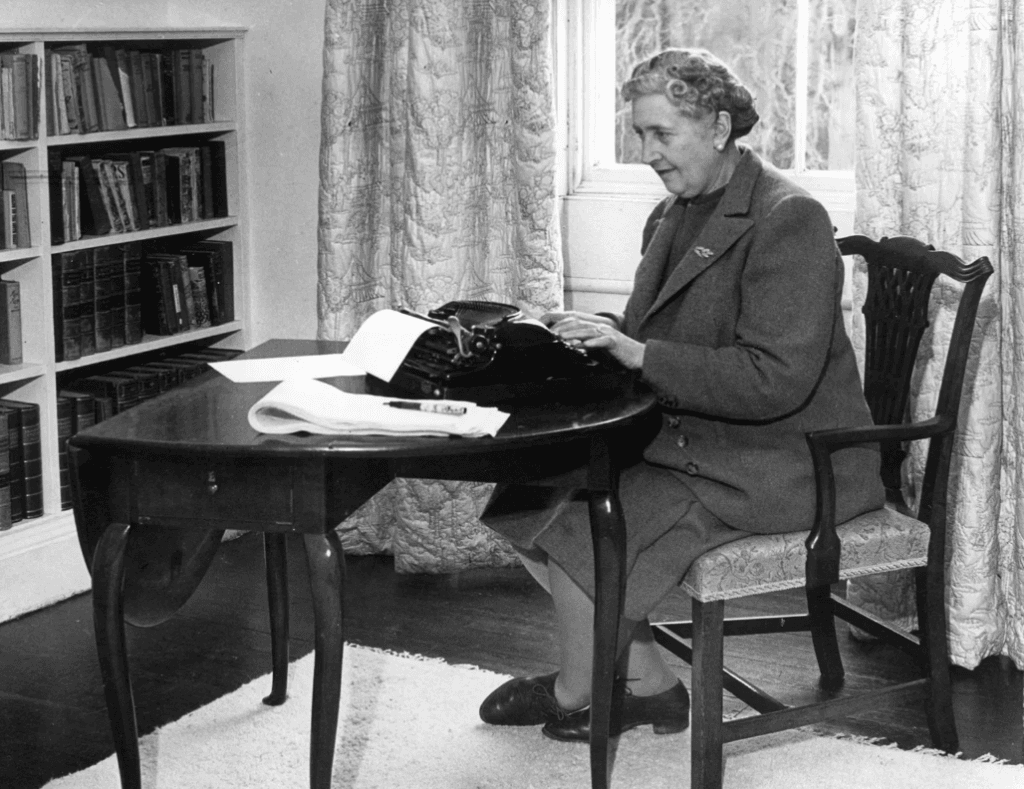

It perhaps dates back to the notion that women cannot stomach crime, death, and murder and must read something light-hearted in fiction. Which, of course, was a mere assumption soon diminished by the queen of crime and mystery, Agatha Christie. It is interesting to note how women must prove themselves away from the light-hearted plots to be taken seriously. This comes even after a large majority of classics and iconic works are written by women—Jane Austen, the Bronte Sisters, Margaret Atwood, and Maya Angelou, among others.

There has been discourse over the years about undermining the romance genre and deeming it to be inferior to, say, historical fiction, literary fiction, sci-fi, and thriller. While it’s true that romances guarantee an HEA or a happily ever after, they are intriguing and often unpredictable reads with realistic, three-dimensional characters with opinions of their own. They represent strong characters with realistic struggles and baggage while including social commentary as well. Women’s fiction seems to have an edge, especially in light-hearted plots, which is the relational aspect. When the audience sees a part of themselves represented in a book, it appeals to them in a way no other genre is much able to. That’s what makes them truly unputdownable.

NYT bestselling author Amor Towles expressed that “the emotional connection to the characters and novels is really unlike anything” in the arts in an interview with TODAY. “It’s a wonderful thing to go through that process because, we know this really scientifically at this point, that’s where we build empathy,” he said.

With mental health becoming increasingly a common topic of discussion, seeing your deepest struggles reflected in the characters you read is a comfort of its own. Hall iterated, “Through storytelling, chick lit re-theorises ways of going through life as a woman—and I think that’s never not going to be popular or necessary.”

Patriarchy and Women’s Fiction

The patronising term has roots in patriarchy, which still tends to believe that women are supposed to be secondary characters who are bereft of agency. Whereas in reality, women’s characters in contemporary fiction can have autonomy without being devoid of a feminist lens. The subtlety in their actions and words does not undermine their feminism and does not make them inferior to other characters.

Kathryn M. O’Neil from The University of Texas, Rio Grande Valley, stated in her thesis on “Women’s Rhetoric and the Romance Novel Genre,” “Perhaps the disproportionate reaction against the genre reveals hidden elitism and misogyny. After all, what does it say about someone who gives themselves permission to shame someone’s choice of reading material? If we say women lack the capacity to choose their own books wisely, we’ve relegated these women to the same status as children, who must be protected against their own inclinations as well as an industry intent on parting them from their money.”

This diminishing of women’s fiction was a practice long before chick lit even started. Women writers are not scarce, but the people taking them seriously still are. BookTok favourite, Beach Read by Emily Henry focused on this aspect of comparison of fiction genres wherein the protagonists get into a debate about literary fiction being considered better or superior than romance. It shows how women authors are reduced to “just a romance writer” without being acknowledged for their writing talent. Words like “flowery,” “fluffy,” and “sentimental,” reek of misogyny, which has less to do with the plot and more with the writers and genre as a whole.

Gendering of the genres

There seems to be a trend that likes adding the word “women” or “female” to denote that it’s supposedly respectfully different, although there is no male equivalent since men are considered the convention in these (and most) instances. Examples include female doctors, female journalists, and the task at hand, women’s fiction. American novelist Barbara Linn Probst talks about genre and gender by mentioning that she would prefer the category of contemporary fiction over women’s fiction. She argues in her article that there seems to be no need to mention the gender of the author or reader in the genre and seeks to find an alternative to women’s fiction as well. She also argued that stories set in the present and framed around the search for self, intimacy, and fulfilment—with plots and character arcs—can simply be called contemporary fiction, the same way that books set in the past are simply called historical fiction.

A common test to determine accurate and meaningful female representation is the Bechdel Test, which was created in the 1980’s. It requires answers to three simple questions, which are: does the work have at least two women? Do they have a one-on-one conversation? Is the conversation about a topic other than men? This helps determine basic women’s representation in the work but often falls short in racial and linguistic representation due to its vague nature. This constant gendering of genres both overtly and subtly ignores the gender non-conforming, non-binary, and trans population. It boils down to the patriarchy, which also tends to dictate what women read based on their gender.

There have been light-hearted novels marketed and reviewed as romance or chick lit while being trailblazing works of fiction, bringing up socially relevant themes within the plot, and having respectful representation through a diverse cast. It takes skill and talent to connect with the audience through words, with characters both believable and realistic, and a story that is pure fiction. There are also contemporary fiction novels written by women with a female protagonist that focus on their lives at length in a gripping plot and are filled with important themes and discussions (think the Taylor Jenkins Reid multiverse).

Writers feel the need to stray clear from being called chick lit authors and often see it as a demeaning label. Writing fiction of any kind takes skill and talent and cannot be shrugged off as “meaningless” or “inferior” in comparison to another genre. With the life lessons, tear-jerking plots, and quotes that stay with the reader for months, chick-lit is a legitimate genre of fiction that deserves literary recognition and definitely needs a better name to be referred to by.

About the author(s)

Sara Siddiqui is a freelance journalist from Delhi. Her passion for writing and the need for social justice drew her to journalism. She believes words can change the world. Sara has bylines in the Indian Express and the Millennium Post as well as published work online. She posts her original poems, book reviews, and personal essays on her WordPress blog.

I loved this piece and the articulation of rethinking labels dished out to works by women unwittingly which are harmful