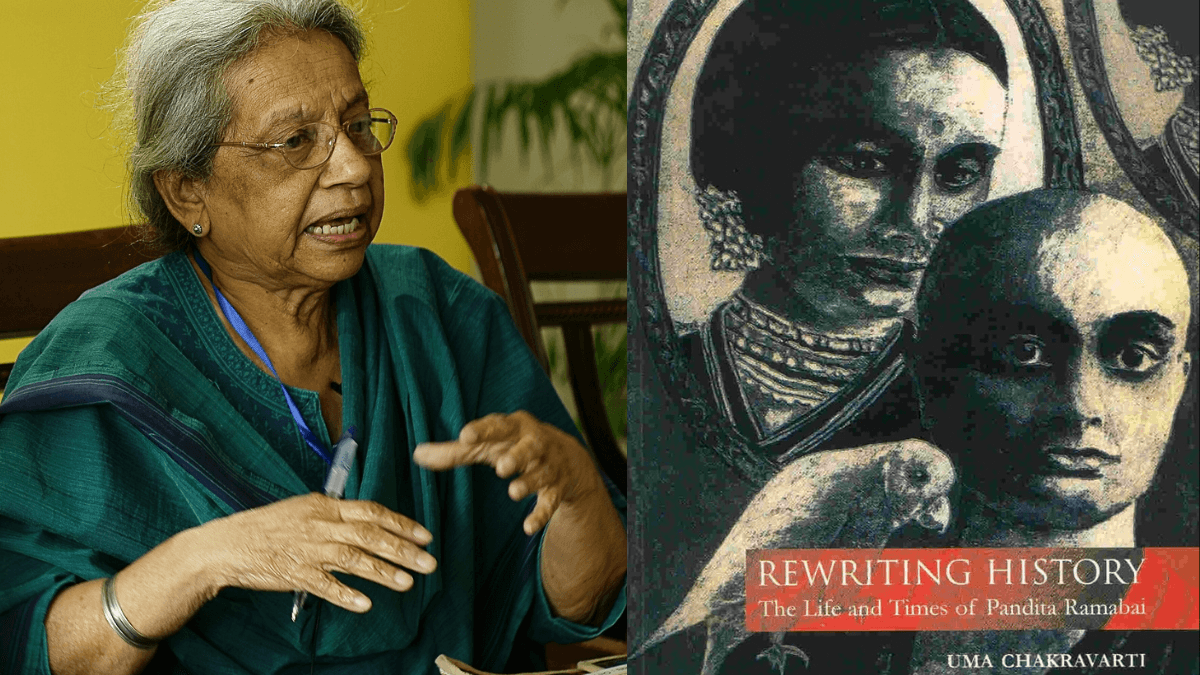

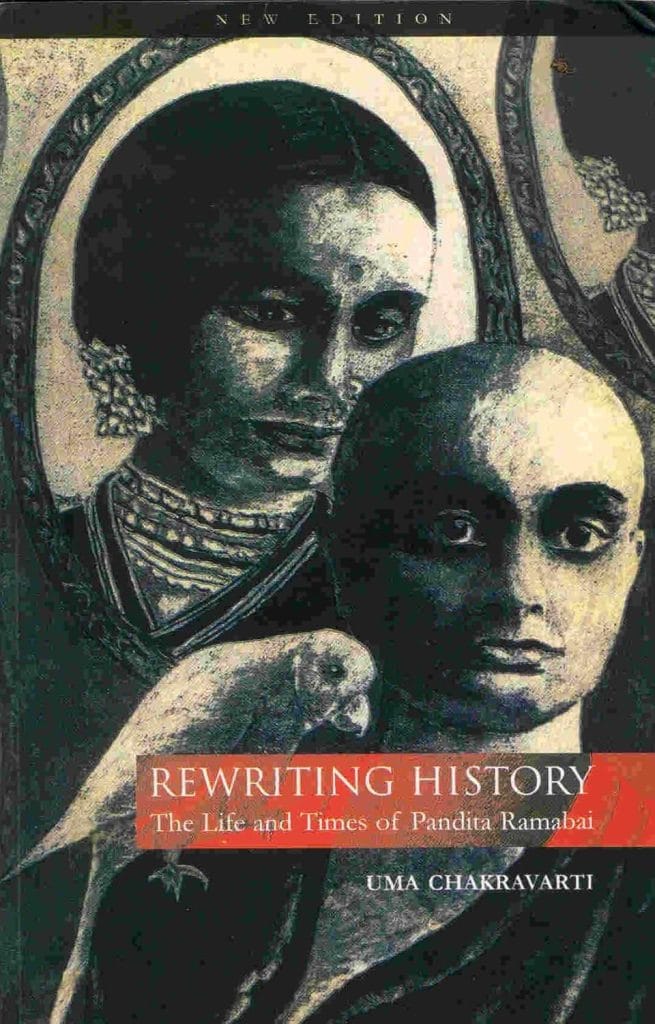

Rewriting history, the title itself challenges the traditional patriarchal historiography. Uma Chakravarti, in her iconoclast study on Pandita Ramabai, not only discussed the plight of women but, like her previous classic ‘Gendering Caste,’ took an intersectional feminist approach in her study. She built her study with the help of the deconstruction theory of Jaques Derrida and works of feminist historians like Gerda Lerner and Kumkum Sangari. She used primary sources as accounts of Ramabai and also letters of widows from the widow ashram in Poona established by Ramabai. Her study on Ramabai and 18th-19th century Maharashtra is important in the field of gender studies and Indian history.

The book starts with the discussion of the 18th century and how caste, class, and gender reshaped Marathi society back then. The book has one chapter on the life of Ramabai, and it is merely 50 pages, while most of the book discusses the transformation of the traditional patriarchal system to a new form of patriarchy, which was also discussed by Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaidya in their book ‘Recasting Women.’

The most important and newer study in the book is the Brahmanical control over women among Chitpavan Brahmins, how Brahaminical patriarchy perpetuates and the control over women’s mobility; it also includes the controlling education of lowered castes.

18th century, gender and caste relations in Maharashtra

Uma Chakravarti argued that these ideals of Brahmanical patriarchy were patronised and glorified by the high-caste Peshwas. The control of women’s sexuality and restrictions through Brahmanical patriarchy by Peshwas and the upper caste is one of the major themes she explored in the first part of the book.

One of the examples discussed in the book is a Brahmin widow who didn’t give up her hair, and instead, she grew her hair later on. She had relations with a lowered caste man, and she had a son from that man. After this incident, Peshwa ordered hard labour punishment for her. Another important discourse Uma Chakravarti brought up was the life of widows during the pre-colonial and early colonial periods. Brahmin and upper caste widows were not allowed to acquire mohmaya (worldly desires), had to give up their hair, were not allowed to eat spicy food, and so on. But in the case of lowered castes, these rituals were not followed; communities like Kunbi have laws regarding widow remarriage, which was quite common.

Colonial milieu and gender relations in The Life And Times Of Pandita Ramabai

The next phase of the book delves into the rise of colonial power in Deccan and its impact on gender relations. The new oriental discourses started by orientalist scholars impacted the condition of high-caste women. Oriental discourses glorified and argued women in Vedic civilisation had a higher position. Historians like A.S. Atlekar also glorified the position of women in ancient India, which created new discourses around women’s law and their mobility, which the book explains very lucidly. In her essay on Vedic women and oriental discourses, she also pointed out some points, but here she talks about the context of Marathi society.

All the discourses surrounding women and lowered castes create situations that control their mobilities more. Colonial laws were othering the Indian women, and their bodies became battlegrounds for the British civilisation mission. White men became the saviours of brown women, as pointed out by many postcolonial scholars. On the other hand, the oriental discourses gave more freedom to Brahmins to control their women’s mobility, and these years of early colonialism became a misery for especially widows.

Reform movement and transition of patriarchal orders

Most of our historical consciousness is about the reform movement in the 19th century as the movement that led to modernisation and brought women into better positions, but Uma Chakravarti deconstructed this myth and argued that the reformers themselves had a lot of patriarchal attitudes towards women. She further explores the role of reformers like M. G. Ranade and Pratharna Samaj to reinforce the idea of an ideal Vedic woman. She also mentioned the attitude of early nationalists like B. G. Tilak toward widows; one of the arguments of Tilak mentioned in the book is that, when a widow refuses to marry and tries to inherit her husband’s property, she should be punished strictly.

The book’s major focus during reform time is on the critique of M. G. Ranade; he also had the same attitude toward widows as Tilak. These attitudes come from the larger framework of controlling women’s sexuality and mobility. For these reformers, marriage is the must and the goal of women’s lives; they reinforce the same norms, where women can’t live without their husbands. Ranade also suggests to widows who got married to be pativrata (obedient to their husbands); if they are not obedient, they should be punished.

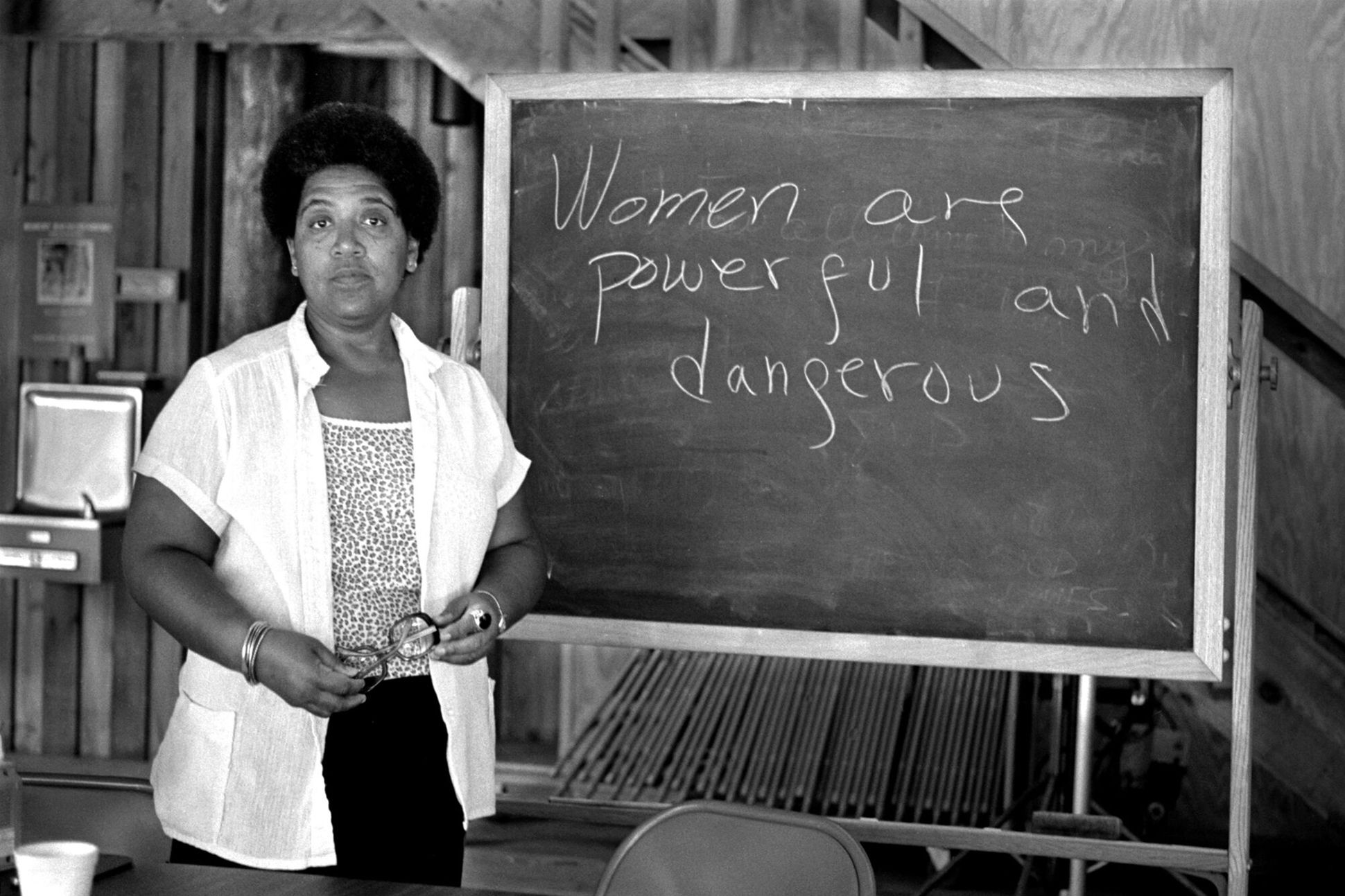

These attitudes toward women led to a new form of patriarchy, where women’s sexuality, their mobility, and their property rights were controlled by the institution of marriage. When one woman did not reinforce these ideas, she became the target of these so-called reformers. Ramabai resisted these norms and parochial reforms; that’s why she became a target of these reformers.

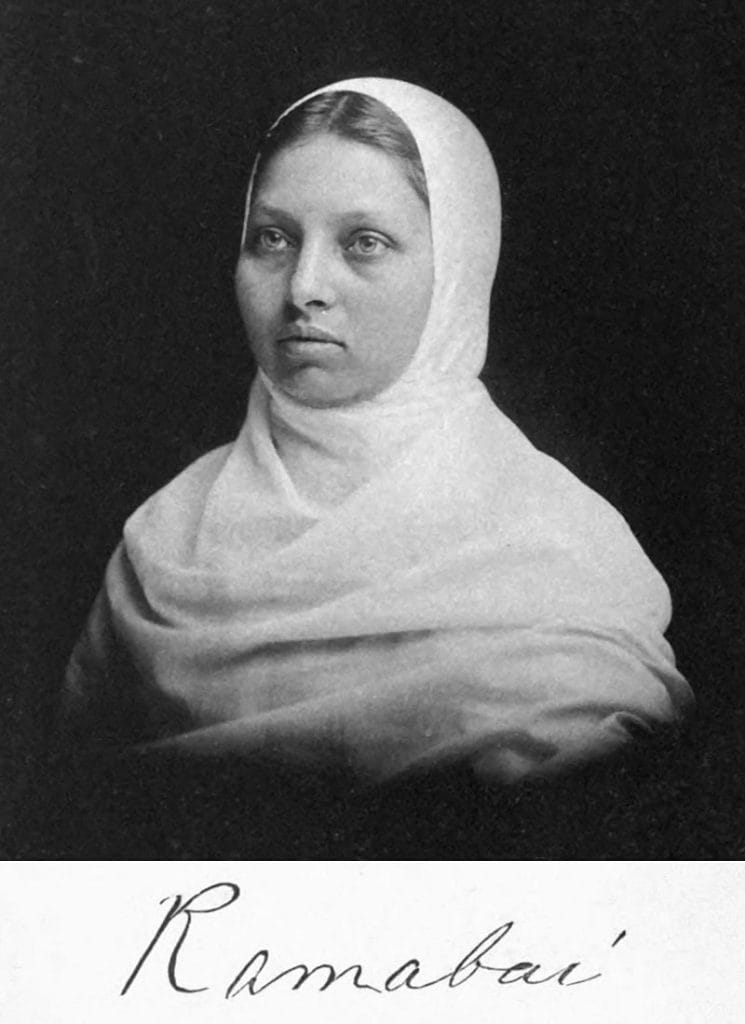

Pandita Ramabai and her contribution to feminist thought

Pandita Ramabai was one of the pioneers of the feminist movement in India. She was the Brahmin widow at that time, and she challenged the patriarchal norms. The book also discusses her relations with reformers like Jyotiba Phule; Phule and Ramabai often worked together to lead non-brahmin reform movements in Maharashtra. Phule opened the first shelter home for women in Maharashtra; he and his wife, Savitribai Phule, worked for women’s education in their entire lives.

.

Ramabai’s conversion to Christianity, often viewed with scepticism by her contemporaries, became a powerful act of self-determination in Uma Chakravarti’s view. This decision also shows profound change in societal norms and underscores the need for personal agency in shaping one’s identity. Ramabai’s conversion and her advocacy for women, especially widows, challenged the patriarchal norms under which she lived. By stepping outside the confines of Hindu orthodoxy, she resisted not only her marginalised position but also the societal expectations imposed by patriarchal norms. Uma Chakravarti shows thoroughly the tensions between tradition and modernity and also posits her argument over how Ramabai’s choices were both personal and political.

Ramabai also, with the help of M. G. Ranade, opened the ashram (shelter) for the widows. But within time, Ramabai and Ranade had some differences, and it led to the blockage of funding for the shelter home. At the same time, Ramabai also faced challenges to get funds from her American followers. The visit of Swami Vivekanand to the USA led to controversy amongst the followers of Ramabai and Vivekanand. Ramabai and Vivekanand had a lot of differences; they never came up with the differences openly and never criticised each other directly. Swami Vivekanand wanted to show India treats her widows with gratitude, whereas Ramabai openly attacked the system that targets women, especially widows. Vivekanand’s followers criticised Ramabai for showing India’s mistreatment of widows.

In her book Uma Chakravarti, which depicts Ramabai’s life sensitively and shows how her loneliness led to her conversion to Christianity, she further argues that Ramabai maintained her independence while opposing her so-called collaborators, the colonial authority, and their policies during the plague epidemic of 1897. Towards the end of the book, she concluded by pointing out that Pandita Ramabai and Jyotiba Phule were reformers who worked for the marginalised and not against the nation, but the nation betrayed them by not giving them importance in nationalist discourses. Uma Chakravarti’s book is a must read and also an important contribution to the fields of sociology, gender studies, and history.

About the author(s)

Faga Jaypal is a final year history student at Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi, with a keen interest in intellectual history, gender and sexuality studies, social justice, and cultural studies. Passionate about literature, books, and museums, he combines his love for storytelling with academic research. Aspiring to become a teacher like Mr. Keating, he seeks to explore history through diverse narratives.