I was brought up in a house located in a conservative area. Since childhood, I have been determined to challenge existing societal norms. In my area, the notion of ‘Shareef Gharana,‘ or respected family, prevails to such a great extent that it reminds me of a couplet by Mustaq Ahmad Yusufi, “Shareef Gharano mai aayi hui dulhan aur janwar toh marr kar hi nikalte hai.“

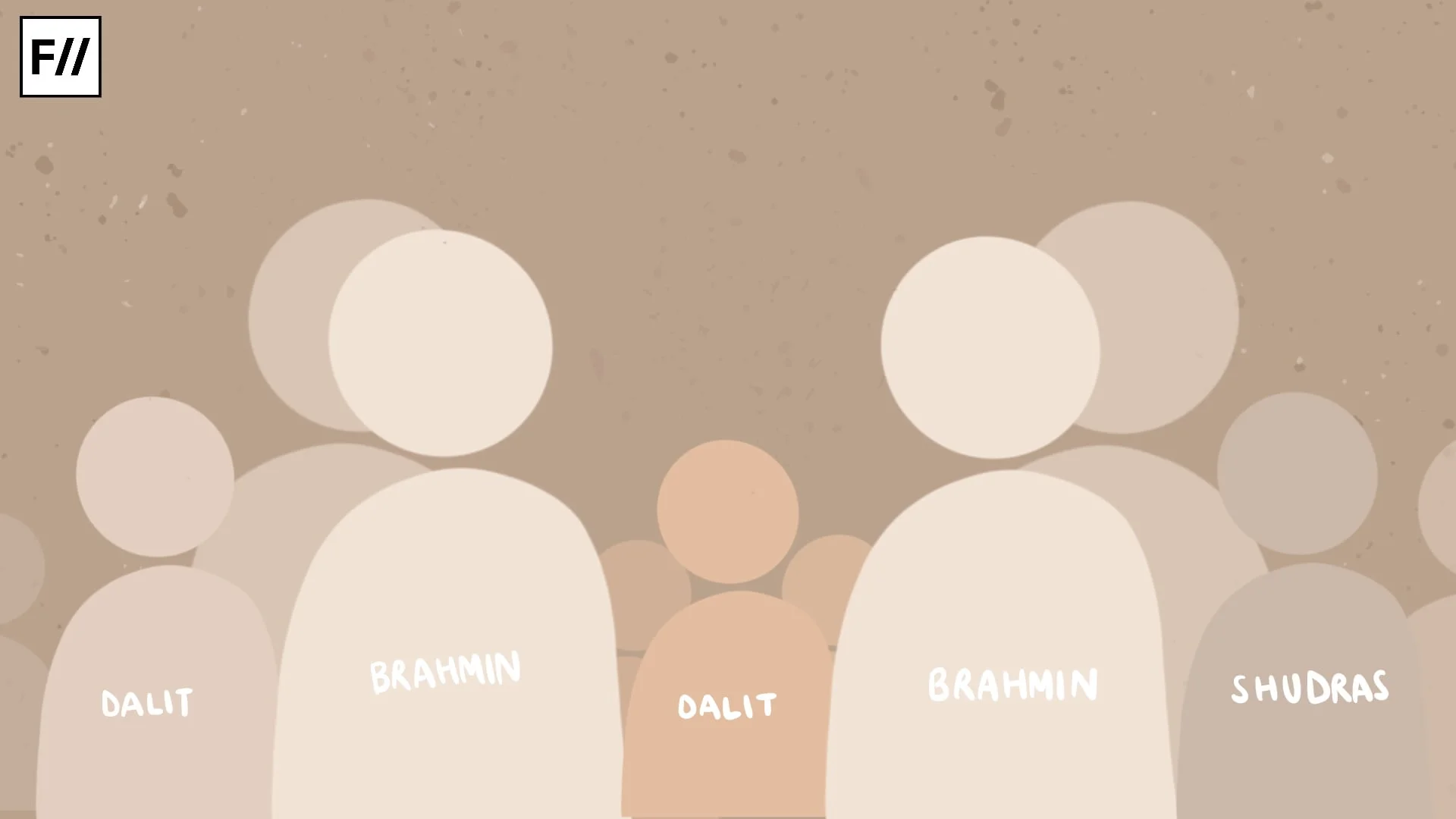

The prevalence of the caste or biradari system in my area demonstrates upper-caste people dominating its culture and norms. The assimilation into their culture creates obstacles to socialisation, development, and growth. It is crystal clear that the upper-caste dominance in an area shapes its culture.

I had my elementary education at an English convent school where I lacked motivation and support from peers and teachers to work on my weaknesses. I would go to a coaching centre to come to par with other students to escape embarrassment in the class and make friends, but as days turned into years, I became a part of a joke at the centre. I remember once I was taunted in the coaching centre’s classroom by my teacher. They said, “Why do you not take up home science and learn some delicious recipes from your mother?“

The taunt shook me to a great extent and made me question my worth because despite making attempts to become good in studies, I could not become a better student. In an attempt to attain formal education, homebound education was being imparted to me. However, my dedication and hard work propelled me to unprecedented heights. In the midst of patriarchal slurs, I was turning into a non-conformist.

Hence, it is evident that homebound education is no longer confined to houses where you live. It has gone beyond its limits and been incorporated into educational institutions. ‘Shareef Gharana,’ and homebound education are interlocked, creating the notion of idealisation. It is largely believed that an ideally educated woman remains at home to raise ideal children and be submissive to her husband’s decisions. It is expected from a girl to give up her aspirations and take up her sole responsibility to maintain household. In fact, I am used to hearing this a lot: “beta, khana pakana aur khilana hi kaam aayega.“

Luckily, I held an agency to get admission to any central university despite the fact that I was raised within patriarchal parameters. It is true I could not develop that attachment with my father, which I wish I could. Though he is not progressive, his perspective to make me educated is not like many other patriarchs.

When I decided to get enrolled at a central university, it was a proud moment for me because no girl in my family had been to a higher educational institution and stayed outside. I chose Aligarh Muslim University, but huge condemnation was lobbed against the decision by my relatives because I was a girl.

Before enrolling at AMU, I was unaware that being expressive in the name of Tehzeeb, as the educational institution is known, is difficult. Reading books and articles helped me embrace sociopolitical consciousness, which allows us to critically understand our social surroundings, take a stance, and remain expressive. In graduation, I studied Islamic Studies, which taught me that education is essential for everyone in order to develop one’s identity and resist exploitation and injustice, and sociology instilled in me its clarity.

During my master’s program at DU, I was able to learn about labour and gender history from some of the most notable historians. From that point on, I became interested in connecting the two to investigate how people are pushed to the fringes. It has become evident to me that being apolitical means missing out on critical analysis in order to delve deeply into the core causes of people’s marginalisation and invisibility.

My changing perspective helps me a lot to grasp Shareef and Tehzeeb, which are used to sustain the dominating power system. That is my feminist joy.

About the author(s)

Nashra Rehman finds her profound interest in addressing the plight of Muslim women and their unappreciated marginalisation. Her focus remains on bringing a novel argument to life.