The recent rape incident at Pune’s Swargate bus terminus is not just a horrific crime; it is a mirror reflecting the deep-seated patriarchal structures, systemic failures, and societal apathy that continue to plague India’s approach to gender-based violence. From a sociological perspective, this incident is a microcosm of broader issues: the normalisation of sexual violence, the culture of victim-blaming, and the failure of public institutions to ensure safety for women, especially those from marginalised communities.

From a sociological perspective, this incident is a microcosm of broader issues: the normalisation of sexual violence, the culture of victim-blaming, and the failure of public institutions to ensure safety for women, especially those from marginalised communities.

To truly understand the gravity of this incident, we need to delve deeper into the layers of societal norms, institutional neglect, and the lived realities of women like Lavanya, whose heartbreaking statement—’I lived in New Delhi before this and always thought Maharashtra was safer for women in that way. But look at this—this is almost like the Nirbhaya case‘—reveals the disillusionment many women feel about the illusion of safety in urban spaces.

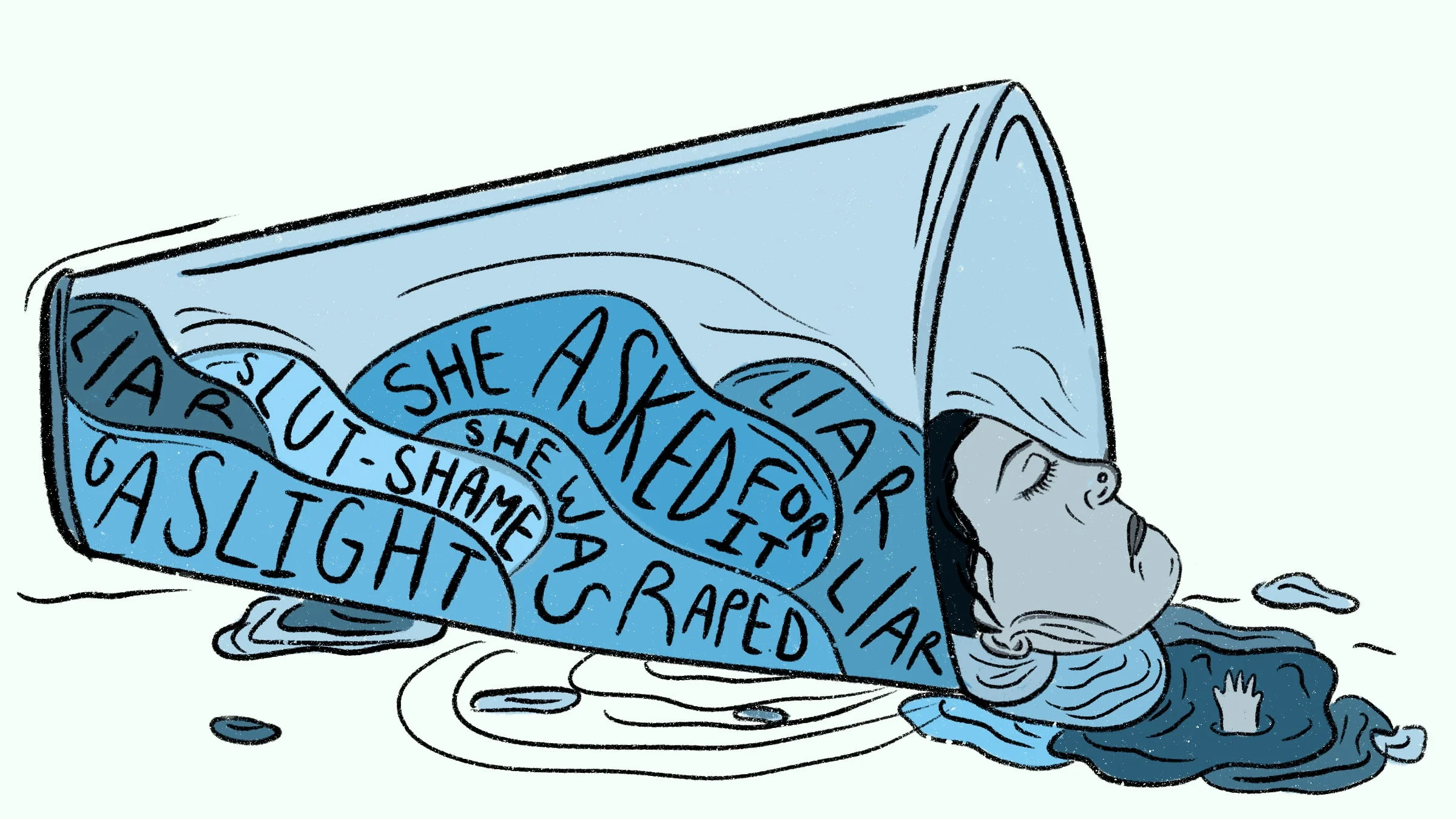

Patriarchal narratives and victim-blaming: the burden of “respectability” on women

The comments made by Maharashtra Minister Yogesh Kadam and the accused’s lawyer, Sajid Shah, are emblematic of the patriarchal mindset that pervades Indian society. By suggesting that the survivor should have “screamed” or “resisted,” they shift the burden of responsibility onto the victim, implying that her actions somehow justified the crime.

This narrative is not new; it echoes the age-old trope that women are responsible for their own safety and that any deviation from societal norms—like being out early in the morning or trusting a stranger—makes them complicit in the crime. Such rhetoric reinforces the idea that women’s bodies are public property, subject to scrutiny and control, while absolving men of accountability.

The Marathi saying, ‘Saat chya aat gharaat‘ (Good girls are back home by 7 pm), encapsulates this regressive mindset. It perpetuates the notion that women who step outside the boundaries of “respectability” are inviting trouble. This not only restricts women’s mobility but also normalises the idea that public spaces are inherently unsafe for them. The fact that such attitudes persist, even among those in positions of power, highlights the urgent need for societal re-education and a shift in cultural norms.

Systemic failures and institutional apathy: the illusion of safety

The Swargate bus depot, despite being a bustling public space, was poorly lit and lacked adequate security, making it a hotspot for illicit activities. The presence of abandoned buses filled with alcohol bottles and condoms points to a long-standing neglect of public safety. The fact that MSRTC employees had previously raised concerns about security but were ignored underscores the apathy of authorities towards women’s safety.

Lavanya’s statement reflects the disillusionment many women feel when they realise that the promise of safety in cities or states like Maharashtra is often just an illusion.

Lavanya’s statement reflects the disillusionment many women feel when they realise that the promise of safety in cities or states like Maharashtra is often just an illusion. For many women, especially those migrating from rural areas or other states, Maharashtra is seen as a place of relative progress and safety compared to regions like Delhi, which has been infamous for its high rates of gender-based violence.

But the reality is far grimmer. The lack of safe, well-lit public spaces, reliable public transport, and proactive policing makes cities like Pune just as dangerous, if not more so, for women.

The police’s response, while commendable in some aspects (such as the swift arrest of the accused), also reflects a reactive rather than proactive approach to crime prevention. DCP Smartana Patil’s statement that it is impossible to patrol every corner of the city 24/7, while true, does little to address the underlying issue: the lack of a comprehensive strategy to make public spaces safer for women. The focus should be on creating an environment where women feel secure, rather than placing the onus on them to “scream” or “resist.”

Class and gender intersectionality: the invisible struggles of working-class women

The survivor, like many working-class women in Pune, was a migrant worker relying on public transport to commute. This highlights the intersection of class and gender in shaping women’s experiences of violence. Working-class women, especially migrants, often have no choice but to travel early in the morning or late at night, making them more vulnerable to harassment and assault. The lack of safe, affordable, and reliable public transport further exacerbates their vulnerability.

The incident also underscores the invisibility of working-class women in public discourse. While the outrage over the rape is justified, it often overlooks the structural inequalities that make women from marginalised communities more susceptible to violence. The focus on individual crimes, rather than systemic issues, risks reducing the problem to a series of isolated incidents rather than addressing the root causes.

Political opportunism and lack of accountability: the nexus of crime and power

The politicisation of the incident, with opposition leaders vandalising public property and ruling party leaders making insensitive remarks, reflects the broader failure of political institutions to address gender-based violence. Instead of focusing on systemic reforms, such as improving public safety or addressing the patriarchal mindset, politicians are more concerned with scoring political points. This not only trivialises the issue but also diverts attention from the need for long-term solutions.

The alleged links between the accused and local politicians further highlight the nexus between crime and politics in India. The fact that the accused was a history-sheeter with multiple cases against him raises questions about why he was not monitored more closely. It also points to the culture of impunity that allows repeat offenders to evade justice, often with the help of political connections. This culture of impunity is not just a failure of the justice system; it’s a failure of society as a whole to hold those in power accountable.

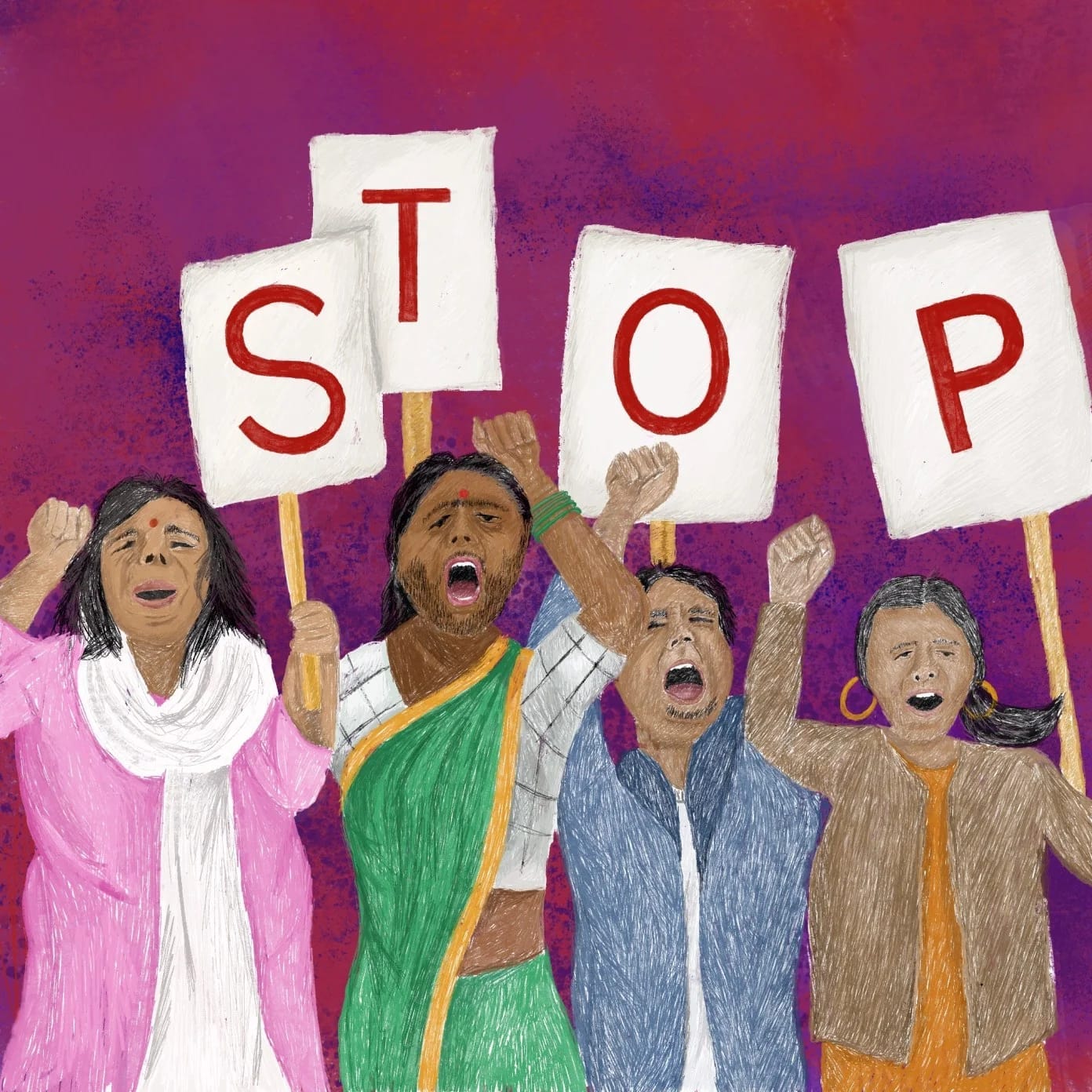

The need for a societal shift: beyond legal measures

While legal measures, such as stricter punishments and faster trials, are important, they are not enough to address the root causes of gender-based violence. What is needed is a fundamental shift in societal attitudes towards women. This includes challenging the normalisation of sexual violence, dismantling patriarchal norms, and creating a culture of accountability where perpetrators are held responsible for their actions.

Activists like Swapanaja Limkar are right in emphasising that the fight against gender-based violence is not just about reacting to individual crimes but about challenging the systemic capitalist patriarchy that perpetuates such violence. Campaigns like the one conducted by the Stree Mukti League, which focus on raising awareness and empowering women to demand their right to safety, are a step in the right direction. However, such efforts need to be supported by institutional reforms and a collective societal commitment to gender equality.

About the author(s)

Shrishti is currently pursuing her Masters in Sociology from Banaras Hindu University. She has a keen research interest in Gender and Digital platform, Gender and Public policy and Media studies.