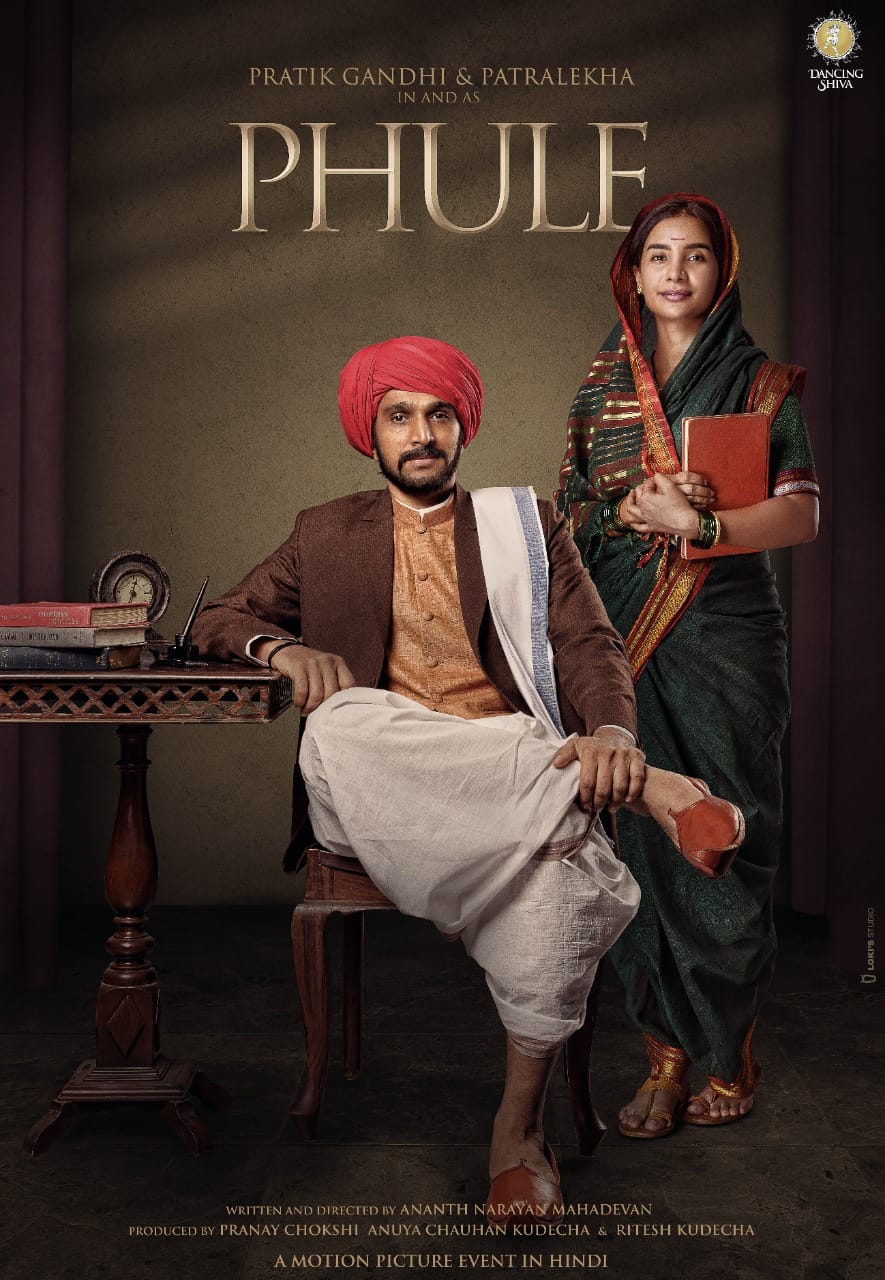

In April 2025, just days before its scheduled release, the Hindi film Phule—based on the lives of anti-caste reformers Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule—was asked to cut out key references to caste.

The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) asked the filmmakers to remove terms like “Mahar,” “Mang,” “Peshwai,” and even “Manu’s system of caste.” These were labeled as “sensitive.” The voiceover on the 3,000-year-old history of caste slavery was softened to say only “ancient.”

This might be a small change. But it tells a much bigger story—about how caste power still controls what can be said, seen, or remembered in India. Especially when those speaking up are voices from the minorities.

What was removed—and why it matters

The cuts ordered by CBFC go straight to the heart of what Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule stood for. Their life’s work was to challenge caste hierarchies and fight for the rights of Dalits, Shudras, women, and all those excluded from education and dignity.

To tell their story without naming the very systems they fought—Manusmriti, untouchability, Brahminical control over knowledge and power—is not just censorship. It is erasure.

Removing scenes like the one showing a man forced to wear a broom tied to his waist (a symbol of caste-based humiliation) and replacing it with a more “neutral” scene of cow dung being thrown at Savitribai is more than just a visual change. It takes away the sharp, lived reality of caste oppression and replaces it with something vague—something easier to digest for the savarna gaze.

Caste is not a ‘sensitive term.’ it is a system

The CBFC’s decision came after protests by organisations like the Brahmin Federation and the Akhil Bhartiya Brahmin Samaj, which claimed the film was “one-sided” and would create caste-based tension. Their argument was that the film made Brahmins look bad and ignored the Brahmins who helped Phule.

Their argument was that the film made Brahmins look bad and ignored the Brahmins who helped Phule.

But the point is not about whether some Brahmins supported Phule or not. The point being that Phule’s entire struggle was against a system where caste, particularly Brahminical dominance, was used to deny basic human rights to others.

Taking out that context is like telling a story about apartheid in South Africa without mentioning racism. Or writing about Indian independence without naming the British.

Why the censorship of Phule feels familiar

This is not the first time India has seen such selective censorship. But Phule stands out because it shows how savarna power continues to decide what kind of history is acceptable, and what must be edited, softened, or silenced.

Interestingly, earlier Marathi-language films like Mahatma Phule (1954) and Satyashodhak (2024) did include these caste-based truths. So why censor this film?

One key reason could be language—and reach. Phule is in Hindi. Its audience is not limited to Maharashtra. It is meant for a national audience. And that makes the savarna discomfort louder.

As one academic put it: ‘Let Phule be only for the Maharashtrians. He is not needed on a grand scale.‘

This is a way of keeping radical, anti-caste voices local and invisible. If they stay in regional languages, they can be praised, garlanded, even celebrated. But the moment they speak to the mainstream, they might become a threat.

When biopics become cautionary tales

The film’s director, Ananth Mahadevan, clarified that Phule was based on extensive research and historical sources. Yet, the CBFC demanded major changes—after they had already passed the film with a ‘U’ certificate.

Why the U-turn?

Activists and students say it’s not just about visuals or words. It’s about the message.

Activists and students say it’s not just about visuals or words. It’s about the message. Phule’s writings openly critiqued the Vedas, caste laws, and the Manusmriti. He called them tools of oppression. He used simple, everyday language to speak directly to the oppressed.

That rawness is hard to take for those who want history to be neat, clean, and inoffensive.

Even student leaders from groups like BAPSA (Birsa Ambedkar Phule Students’ Association) say they were unsure if the film would even dare to show the true Phule—bold, angry, visionary. Now, their worst fears might have come true.

Controlling the story, controlling the people: the case of Phule

At the heart of this controversy is a serious question: Who gets to tell the truth in India?

The caste system may be illegal on paper, but its mindset still decides which stories are told and which are censored. Upper-caste groups are not just influencing media or movies—but are shaping public memory.

This kind of control is not about one film. It’s about who gets to define history, whose pain is visible, and whose pride must be protected.

The bigger picture: what the data tells us

While we argue about what can be shown on screen, the reality of caste violence continues offscreen.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), crimes against Scheduled Castes rose by over 13% in 2022 alone. That’s more than 57,000 cases—yet convictions remain shockingly low in many states.

Dalit and Adivasi communities still face not just violence but systemic exclusion—from jobs, housing, education, and justice systems. Many are afraid to even report crimes, fearing no action will be taken.

Dalit and Adivasi communities still face not just violence but systemic exclusion—from jobs, housing, education, and justice systems.

Laws like the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act were created to protect these communities. But implementation remains patchy, and state support is often symbolic. As one example, the Prime Minister washing the feet of sanitation workers made headlines. But does that act replace policy, dignity, or justice?

Why It hurts more when it’s about Phule

Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule were not just reformers. They built the foundation for anti-caste, feminist, and educational movements in India. They opened the first school for girls. They challenged both caste and gender hierarchies—together.

Their words, actions, and dreams laid the path for generations.

So when a film about them is censored, it feels hurt—not just to Dalits or Ambedkarites, but to anyone who believes in equality and justice. It’s not just about a few cut scenes. It’s about whether India is still ready to hear the truth about itself.

The real fight

In today’s India, it is easy to celebrate icons with garlands, posters, and awards. But it is much harder to carry forward their ideas.

We see this in the state’s willingness to demand Bharat Ratna for the Phules on one hand—while silencing their words in cinema on the other. This is not a celebration. It is a contradiction.

We are turning real people into mythological figures—depoliticised, defanged, and made suitable for school textbooks. But the real Phule were not polite; rather, they were loud, clear, and radical.

When we strip away the truth, what survives isn’t memory—it’s a softened story, far from what it really was.

Caste isn’t just past. It’s present.

The censorship of Phule is not an isolated incident. It is a window into the ongoing control of savarna power over media, art, history, and justice.

It reminds us that caste is not just an old system—it is a living reality, shaping whose stories are told and how.

It reminds us that caste is not just an old system—it is a living reality, shaping whose stories are told and how.

This moment asks something of all of us: not just to watch a film, but to ask—Who is allowed to speak? Whose truth is heard? And what are we willing to do when it isn’t?

Because a society that silences its own reformers is not just forgetting its past. It is also failing its future.

About the author(s)

Anushka Bharadwaj is a journalism graduate from SCMC Pune. She is an intersectional feminist with a deep interest in gender, caste, politics, and mental health. When she’s not writing or reading, she’s usually found lost in poetry, dancing to her favourite songs, or discovering new music—always reflecting on the world through stories.