‘It’s for your own good‘ is the phrase the men of Seeing Red keep parroting to the women, no matter if it is a father slapping a girl who is on her period for simply wanting a hug, or a husband telling his wife to continue with her unpaid labour to keep her senile mother-in-law ‘pure’, or a husband chastising his wife for wanting to pursue higher education because virtue demands a wife to be less educated than her husband.

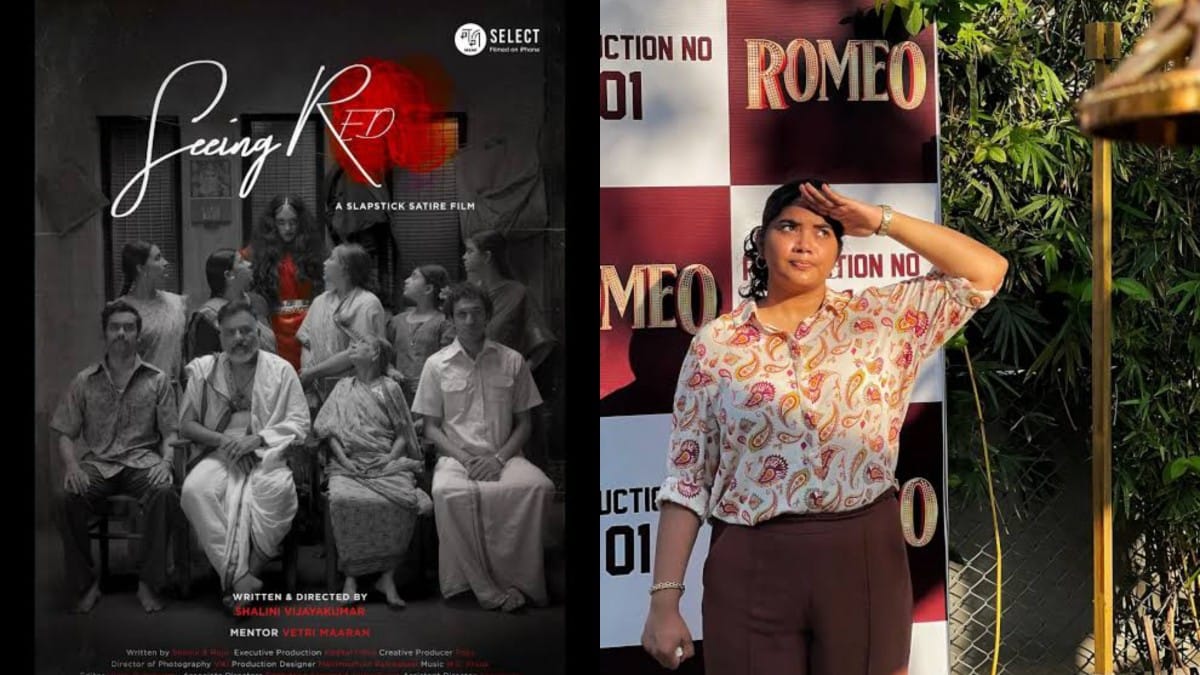

Seeing Red, a short film of 28 minutes directed by Shalini Vijayakumar, tasks itself with outlining the hypocrisy behind such claims where the exploitation and unpaid labour of women is exposed, hidden under layers of societal misogyny and the dogmas of religion and respectability.

Redirection of blame and lack of male accountability

In the poster, there is a Ghost wearing a red saree but only the six women are looking at her; the men look straight ahead at the viewers. The men cannot see the Ghost because they are not suppressing endless rage and wasted potential, they are not preoccupied with erasing their identity.

The familial hierarchy is clear from the get go with the father being the head who gets to slap one son while rewarding the other with his scooter for compliance. Bell Hooks writes in The Will To Change: Men, Masculinity and Love that, ‘In patriarchal culture males are not allowed simply to be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do.‘

This need for men to engage in toxic masculinity in order to perform a masculine identity ensures that the power balance between the men and women of the household is even more crooked where the aggression the son receives from his father must be redirected towards his wife/daughter, often without any consequences.

Protecting female honour: a disguise to uphold male ego?

The men keep theorising why the Ghost has emerged only to end every discussion by displacing the blame upon women. Shashi Deshpande writes in The Long Silence, ‘A woman can never be angry; she can only be neurotic, hysterical, frustrated.‘

Thus, the final conclusion of the men is that the women ‘must have suppressed guilt‘ which effectively frees them from any accountability. Their narrative is clear from the start as a son says, ‘The women suddenly going crazy is disgrace to us but them being possessed invites pity‘.

Their narrative is clear from the start as a son says, ‘The women suddenly going crazy is disgrace to us but them being possessed invites pity‘.

Seeing Red is exposing from the first frame that all the efforts at exorcising the Ghost that follow are not the desire of men to help the women but more actions that will serve to maintain their crystal clear societal image as a pure and chivalric male lead. No man questions his conduct and we are once again breathing in Atwood’s Gilead where it is outlawed that a man could ever be in the wrong. In such an atmosphere it is only fitting that the only woman who seems to be the voice of reason is shush-ed at every chance, her theories discarded like the whispers of old-wives tales.

Purity and power: intersection of caste and gender in Seeing Red

Aveen Maguire in her article ‘Power: Now You See It, Now You Don’t.‘ explains three faces of power using a sociological model. She says the first face of power is ‘visible in direct action‘ or violence against women in the private or public. The second face of power shows itself ‘in attempts to stifle an issue as it emerges, or in attempts to redefine or reshape an issue into something less threatening‘.

She defines the third face of power as the hardest to discern because it is here where power ‘is used to manipulate people’s perceptions‘ and women are coerced into compliance. Shalini Vijayakumar explores all these facets of power through the women whose stories are being told.

Dhivya has to surrender to her husband commanding her not to pursue a masters degree simply because of his insecurity, he says, ‘No woman should fool her husband‘. It pushes us to question why the male pride is linked with suppression of female accomplishment. Women are not even allowed to dream of having a career but the system of marriage goes unquestioned even if it is a set-up where the husband thrives in his life but never acknowledges it is a kingdom built on the sacrifices of his wife and her unpaid labour.

Hema Manni’s husband says, ‘It’s your duty to care for her (patti, mother-in-law) purity as long as she’s alive‘ when she explains the reason behind why she stopped drying her ritual clothes. He uses her words and twists them to portray as if she wants to forsake her mother-in-law all the while demanding absurdly that his mother would care for her ‘purity’ even if she has gone senile.

It is apparent that the only person invested to maintain this concept of purity is the man yet the labour of doing so is displaced upon the woman. When she complains her voice is squashed with slander and all she can do is fume in silence.

When she complains her voice is squashed with slander and all she can do is fume in silence.

The whole family is scared out of their wits but Krithi still does not enter the prayer room. Frustrated, her mother answers it is because she is on her period. Yet, a second later the father reveals the real reason for this religious compliance from his daughter which was a slap she received that very morning from her father. Why? Because she wanted to go inside the prayer room to hug her grandfather but it cannot be defiled by the ‘impure’ Krithi.

India is a land marked with violence for religious, caste and class sentiments yet period blood outclasses everything and becomes the gravest sin and taboo. The patriarchal society remains preoccupied with the purity of a woman yet this ‘symbol’ of her purity makes her unclean and impure.

Another striking way we can see the obsession with purity in the film emerges through its commentary on caste and religion. The rules the women have to abide by to maintain their purity align with their caste. Even with the threat of a ghost the men cannot allow Vippadi Moorkan into their house because they ‘don’t know his caste or religion‘.

They follow through the absurd suggestions of the bank manager and only agree to let Vippadi in their house after deciding to make the women ‘clean the house with phenol‘. The juxtaposition of the presence of religious activities of puja in the background and the men hurling either abuse towards women or casteist remarks exposes the hypocrisy behind the obsession with purity.

Women, rebellion, resistance in Seeing Red

What is the Ghost of Seeing Red if not a materialisation of the bottomless rage these women have been suppressing? Is it not an attempt to travel from the generalised and depersonalised hysteria the men diagnose them with to an understanding and ownership of their anger? Every time the women are wronged and silenced we hear the sound of the puja bell and somewhere hidden in the frame a part of the Ghost surfaces wearing a red saree, the colour that embodies both purity and rage.

As Vippadi arrives ready to whip the women and exorcise the Ghost, the women are left pleading but the dominating, screaming and violent men stand like shrunken mice in a corner. One is transported to the Mahabharata scene where Draupadi was dragged to a sabha filled with men and despite countless appeals her husband stood like cowards in a corner.

There is no need to wait for a godly intervention in Seeing Red because here the women come together, they all see the Ghost and consequently everyone gains a voice.

The Dhivya who could only ‘grumpily fill bath water‘ earlier retorts why the men cannot take the violence they are telling the women to endure because ‘it will be good‘ for them, Hema Manni who was ‘drying the ritual clothes‘ exposes the hypocrisy behind her husband having supreme authority by reminding him that his mother (the true elder of the house) is still alive, and Krithi who was ‘sniffling like a leaking faucet‘ finally comes screaming at her father that ‘all he ever thinks about is beating‘ showing how men use physical and emotional violence to manipulate women into erasing their identities.

Unlike others, Krithi does not feel a bitter sensation in her throat because she is speaking up for herself for the first time. Perhaps the bitterness the other women feel is a representation of their souls dimmed by years of abuse and normalisation of female violence perpetrated by our patriarchal society. In India, seeing rape headlines is as common as watching the sun rise, supreme court judges make statements where the perpetrator is often excused for his crimes without any consequences and the victim undergoes a double-rape.

In India, seeing rape headlines is as common as watching the sun rise, supreme court judges make statements where the perpetrator is often excused for his crimes without any consequences and the victim undergoes a double-rape.

As Roxane Gay asserts in The Careless Language of Sexual Violence, ‘[w]e cannot separate violence in fiction from violence in the world no matter how hard we try.‘ Therefore such a treatment desensitises the population towards violence against women and triggers a victim blaming mentality.

Rage: a space where the personal meets the political

Seeing Red endeavours to break this normalisation of abuse by representing what Judith Halberstam (in their article ‘Imagined Violence/Queer Violence: Representation, Rage, and Resistance‘) calls ‘imagined violence‘, a space where rage becomes political. The power shifts as the whip goes flying into the hands of a woman, they all band together and they scream.

It is not the helpless scream of a victim waiting for a man to save her, it is not the scream of frustration when despite every effort the case of a woman is dismissed and the man goes scot-free with a slap on his hand. This is a roar of female rage where every sentiment of bottled up agony rises up and the men can only cower into the prayer room. The Ghost has finished her work because the women finally “see red” and she leaves for another home, perhaps to help other women see their red.

The music at the end leaves us with a melody that is apt for a song of protest as it says, ‘To bend, bow and take a blow is not truly womanly / To be praised, hailed, and worshipped is not truly womanly / To have my own wants and needs is truly freely womanly‘. Our extremities are exposed where a woman is either treated like an unpaid slave and beaten at the whims of a man or she is deified as a pure goddess where her chastity is conflated into a sign of male honour.

We are also left with an answer as to what womanhood should be which is simply body autonomy, a choice to choose and think for ourselves, a society where our bodies are not male properties where we have to constantly repudiate our existence and fit into the binaries of a slave or a goddess. As Audre Lorde writes, ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare‘.

About the author(s)

Priya Jain has a Bachelors in English Honours from Delhi University. As a writer and poet she wants to strike a balance between cynicism and hope, she wants her work to have a purpose that resonates with people. She is an avid reader of literature written by women and queer writers that challenges gender norms and transgresses societal constructs. Her research interests are intersectional feminism, female rage and queerness