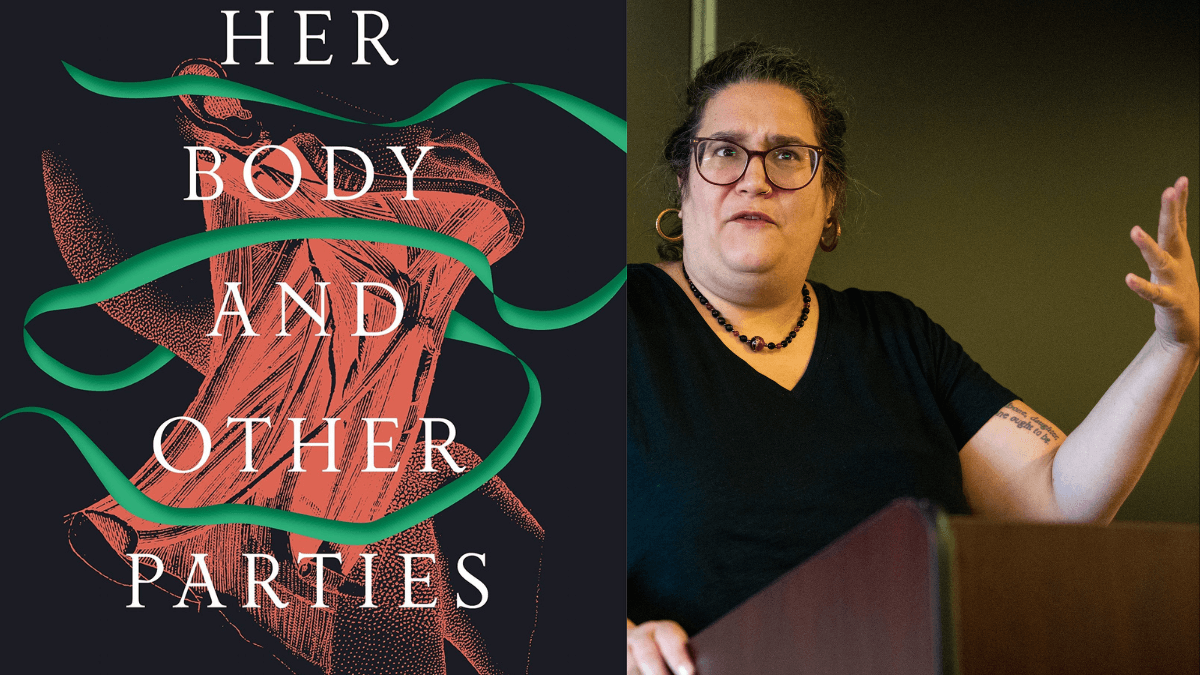

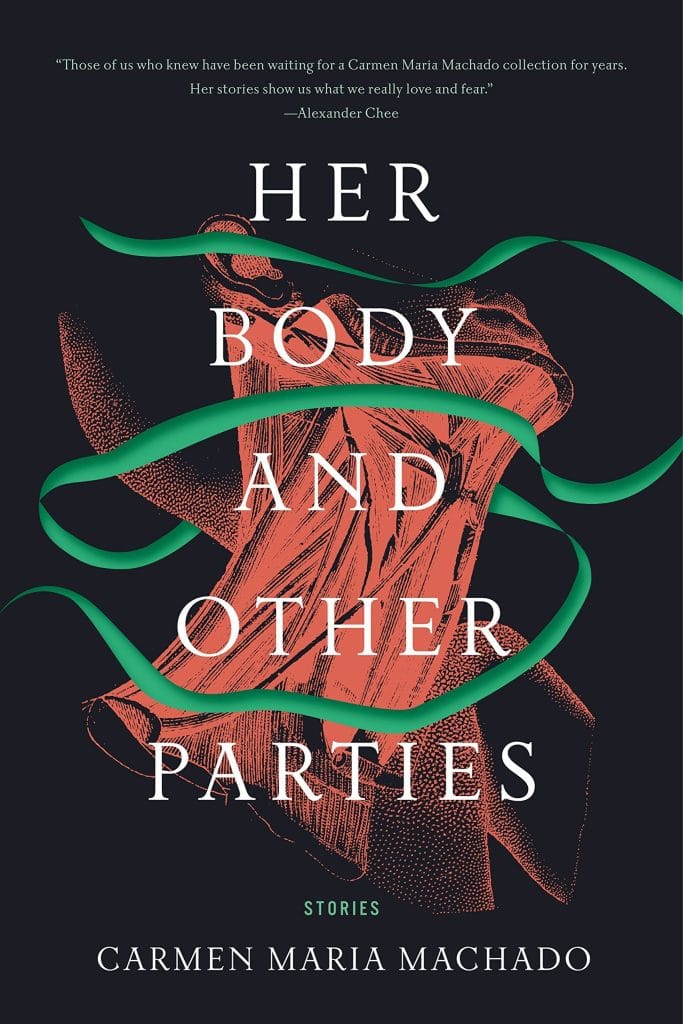

Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties masterfully fuses genres like horror, fantasy, and realism to delve into the layers of gender, sexuality, and the female experience. Through her nuanced and imaginative storytelling, Machado takes on the journey of women navigating trauma, desire, and intersections of identity. Her work challenges traditional narrative structures, all the while giving voice to bodies often marginalised by societal norms.

Carmen Maria Machado writes from the body—with honesty, vulnerability, and a voice that feels personal and sharp. As a queer woman, her experience quietly shapes the emotional weight of each story. Her Body and Other Parties is made up of eight different stories—The Husband Stitch, Inventory, Mothers, Real Women Have Bodies, Especially Heinous, The Resident, Difficult at Parties, and Eight Bites—each one looking at gender, trauma, and the strange violence of being seen, or not seen. In The Resident, for instance, Machado reflects on writing itself, mixing gothic isolation with memory and past hurt in a way that feels deeply raw.

Machado’s stories show how the lives of women are shaped by many things at once, like their gender, sexuality, body, and mental health— bringing intersectionality to life.

Genre as resistance: Rewriting the rules of representation

Carmen Maria Machado disrupts traditional narrative techniques by combining elements of horror, fantasy and realism in one. The blending of genres opens up new narrative possibilities where the fantastical and the real intersect. This way of storytelling allows Machado to examine themes of gender, trauma, and desire beyond the limitations of traditional realism, which often stereotypes women.

By pushing back against traditional norms, Machado offers a layered and deeply personal exploration of the female experience. Her approach to genre isn’t just about style—it’s a form of resistance. Through her storytelling, she captures women’s realities in ways that standard literary forms often fail to do.

In the story The Husband Stitch, for instance, the everyday domestic setting is interwoven with eerie, supernatural elements. Horror becomes more than a genre; it turns into a sharp metaphor for the violence and trauma that so many women face. Here, genre is not just a creative choice; it becomes a way to challenge the very framework of mainstream narratives.

In Her Body and Other Parties, this refusal to follow conventional genre rules feels like a protest in itself—a rejection of the ways literature has historically misrepresented or erased women’s bodies, voices, and identities. Machado uses genre not just to tell stories but to reshape the space in which those stories are told. This helps in the exploration of how the female body, often a site of violence and violation, can also be a space of resistance and autonomy.

The female body: A battleground of violence and autonomy

The female body is a central theme in Her Body and Other Parties, which remains contested, violated and reclaimed. Women’s bodies are shown as sites of trauma but also remain a symbol of resistance and autonomy in stories like The Husband Stitch and The Resident.

Machado examines how societal expectations around beauty, sexuality and identity impose control over women’s bodies. In The Husband Stitch, the narrator’s body is objectified by her husband, who constantly demands more of her. But in the same story, her body also becomes a symbol of resistance, as she claims resistance over the one piece that is uniquely hers—the ribbon around her neck. Machado uses this powerful metaphor to show the female body is not only an object of desire but also where women can assert control over their bodies.

Machado also highlights intersectionality, showcasing how marginalised groups of women experience compound forms of violence. Yet even in pain, their bodies resist and reclaim power, often in subtle and unseen ways. Through her stories Machado reimagines the female body not just as a site of victimhood but also as a symbol of quiet resistance and resilience.

Queer desire and the politics of invisibility

Another key way in which Her Body and Other Parties explores intersectionality is through its depiction of queer desire and politics of invisibility. Queer women, particularly those who don’t conform to heteronormative ideas, face unique challenges in both literature and society.

Stories like Especially Heinous particularly explore how the identity and desires of a queer woman are ignored, challenged or erased both within society and the narrative itself.

Through her storytelling, Machado brings these often silenced identities to the forefront. This not only makes queer desire visible but central to the narrative. Her characters push back against “heterosexual expectations,” claiming their identities through desire. In doing so, Machado disrupts traditional narratives and highlights how queerness intersects with other forms of oppression. The struggles queer women face are also in turn connected to how they carry and express their trauma.

Trauma and memory: Telling stories in pieces

Another key portrayal in Her Body and Other Parties is the portrayal of trauma and memory. Machhado’s characters often face deep emotional and physical trauma, and how they remember and tell these experiences is central to the narrative. Trauma in her stories is not linear and clear but appears in fragmented memories and lingering emotions. Machado resists simplification of trauma but offers a nuanced portrayal, showing how trauma shapes identity and bodily experience.

Machado’s fragmented storytelling reflects how memory often works, especially for women whose experiences are ignored. By depicting trauma in pieces, she challenges simplified or idealised portrayals of it and offers a more honest and layered representation of pain and survival.

Narrative as rebellion: Claiming space through storytelling

Throughout Her Body and Other Parties, storytelling becomes this act of rebellion. The women in Machado’s story are not just telling their stories but taking back their voices, their bodies, and their identities too from everything that’s tried to silence them. And in doing so, they also claim their agency back from all the societal constraints.

Through this act of storytelling, Machado makes a strong point about why representation matters. Women’s stories have often been ignored or twisted, especially those that are queer, non-conforming, or shaped by hurt and trauma. But here, she gives her characters a voice, a space that’s theirs, where they can tell things how they see it. By doing so, she challenges the conventional narratives that have marginalised these voices for an extended period.

Stitching together an archive of resistance

Machado offers a rich , layered portrayal of women’s lives, bodies and identities. By breaking away from conventional form, Machado makes room for stories that reflect the intricate and intersecting experiences of identity and pain. Machado demonstrates how violence and resistance, harmful systems, and the will to survive shape women’s bodies. Through an intersectional feminist lens, she focusses on voices long erased from mainstream literature.

Ultimately, this is more than a story collection; it is a vital contribution to contemporary feminist literature. Machado builds on the legacy of feminist writers that came before her, all the while pushing the canon toward more expansive, inclusive, and experimental forms. In giving voice to the fractured, the queer, and the unseen, she reclaims space and reshapes the future of feminist storytelling.

About the author(s)

Juhi Sanduja is an Editorial Intern at Feminism In India (FII). She is passionate about intersectional feminism, with a keen interest in documenting resistance, feminist histories, and questions of identity. She previously interned at the Centre of Policy Research and Governance (CPRG), Delhi, as a Research Intern. Currently studying English Literature and French, she is particularly interested in how feminist thought can inform public policy and drive social change.