A People’s History of Heaven is a novel written by Mathangi Subramanian, that explores themes of intersecting identities, feminist solidarity, and systemic exclusion. The novel opens in an informal settlement called “Heaven” (Swarga, short for Swargahalli) in Bangalore, which is under threat of being bulldozed to make way for a new construction project. In opposition to this, five young girls (protagonists and narrators of this story): Padma, Banu, Joy, Deepa, and Rukshana form a human chain to resist displacement.

Through this, they not only resist against the government’s apathy, but also the societal norms that constantly marginalise them. This act sets the tone for the novel, which celebrates the resilience, dreams, and quiet revolutions of these young girls.

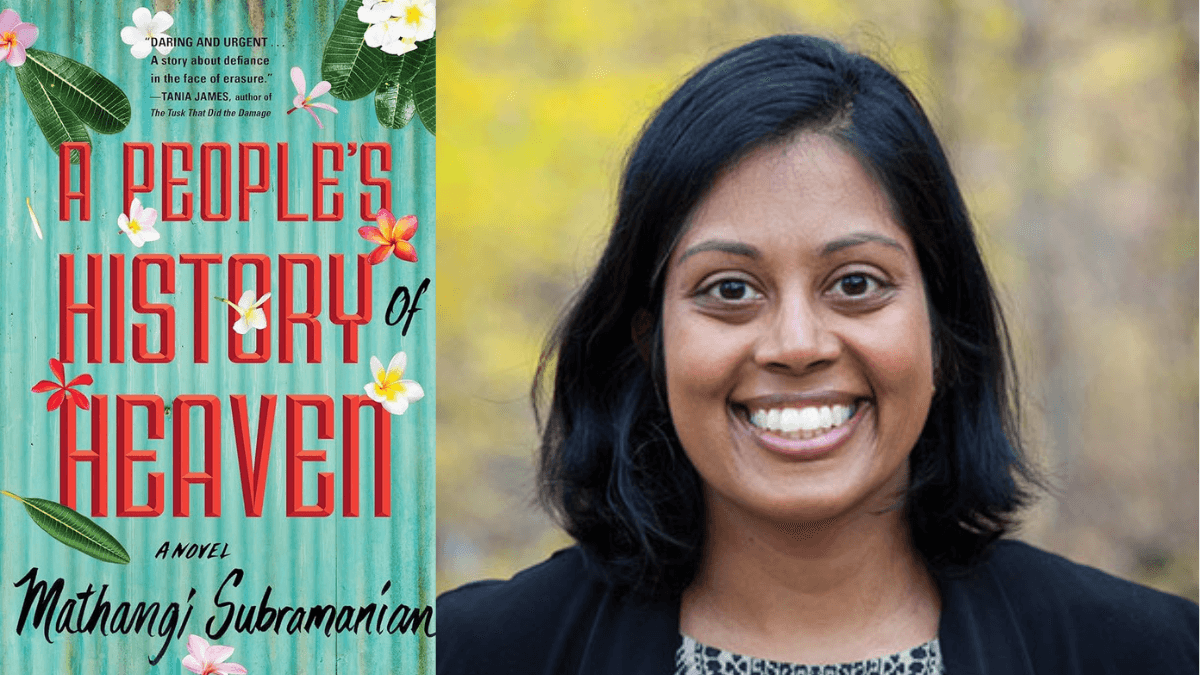

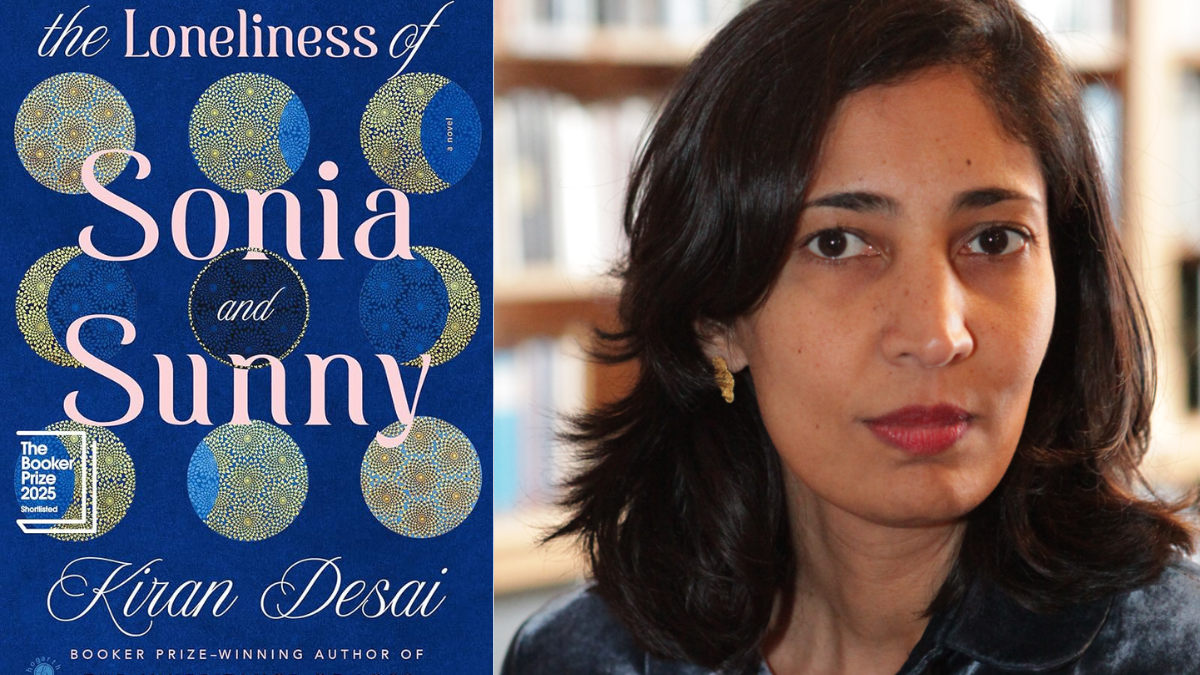

An Indian-American writer and educator, Mathangi Subramanian has based A People’s History of Heaven on her extensive fieldwork working with young girls in informal settlements in Bangalore. Subramanian holds a doctorate in education and communication from Columbia University and has worked with UNICEF and various NGOs across South Asia. She draws from the realities and experiences of young girls of marginalised communities in Bangalore, especially of those in informal settlements.

The protagonists’ cross-cutting identities and spaces in A People’s History of Heaven

A People’s History of Heaven portrays how each character navigates the intersectionality of their own identities. Each of the girls embodies a layered identity: Joy is a transgender Dalit girl; Deepa is visually impaired; Rukshana is a queer Muslim girl; Padma comes from a rural background; and Banu is an aspiring artist from a traditional household. Their identities are shaped by caste, class, religion, physical ability, gender, and education levels. For the girls, these institutions don’t exist separately but overlap, deeply entrenching their experiences of discrimination.

Subramanian effectively shows how the girls don’t merely experience a singular form of exclusion, but are situated at multiple points of social vulnerability.

Heaven, their residence, is a representation of how government policy and development schemes are absent. Their space (makeshift homes, muddy paths, haphazardly planned streets and houses) is proudly claimed by the girls as their dwelling. The lives of the rich, urban elites in Bangalore are distanced (even though some of the girls’ mothers work for them as wage workers), especially the rich’s lifestyle of education, religion and mobility.

Subramanian paints a picture of finding comfort and belonging in Heaven, one that the rest of Bangalore looks down upon or ignores entirely. Subramanian powerfully decimates the perception that marginalised people have ‘bigger problems to worry about‘ and therefore cannot care about identity, dignity, or expression. Contrarily, the girls’ marginalisation sharpens their sensitivity to discrimination. Heaven is perceived as a vibrant, complex space; not merely a backdrop for poverty but a site of dreams, defiance, and daily survival.

Collective voices as feminist solidarity

The New York Times, in their review of Subramanian’s A People’s History of Heaven, points out the narrative of a collective voice that unites the stories of the girls and their communities. Subramanian’s choice of writing multiple narrators is crucial because it displays a spirit of feminist solidarity, where resistance is collective and mutual support is the key. Another commendable effort on Subramanian’s part, is how she consciously avoids misery narratives in A People’s History of Heaven.

These girls are not mere victims of a broken system. They are active agents of change, who support each other through friendship, strength, support and love.

These girls are not mere victims of a broken system. They are active agents of change, who support each other through friendship, strength, support and love. Their defiance lies in everyday actions like resisting eviction, claiming education, and expressing identity. For example, when Deepa is excluded from a dance competition because of her blindness, her friends affirm her worth without pity. They support one another not with sympathy, but with solidarity.

As A People’s History of Heaven shifts from one girl’s perspective to another, readers witness how the girls view each other with affection, awe, and respect. Joy, for instance, is not merely accepted for being transgender; she is admired for her intelligence and strength. Among their group, feminist solidarity is not a theoretical concept but a lived reality. It is found in shared meals, whispered secrets, fierce protection, and small acts of everyday resistance. In this way, the book subverts the reader’s expectations by offering a narrative of hope rather than despair.

A narrative of seeing and unseeing bias in A People’s History of Heaven

The girls encounter various developmental challenges and structural barriers. The adults around them are portrayed to accept them as inevitable. However, Subramanian shows how the girls see and resist these biases, without fully subscribing to them in A People’s History of Heaven. Certain adults (like Deepa’s mother) embody structural violence, through internalised casteism, ableism, patriarchy, or religious orthodoxy. Yet, the children see the world differently, not because they are unaware, but because they believe in the possibility of something better.

The girls in A People’s History of Heaven can see the discrimination or bias due to their marginalised status, in terms of acts and situations. They are aware of their mothers’ mentalities of it as well, especially the mentality of ‘this is how it is’. But they unsee it, because they do not perpetuate similar social biases.

Deepa, for instance, is denied opportunities at school because of her blindness. But her friends do not reduce her to her disability. They acknowledge it but do not let it define her worth. Similarly, Joy’s transgender identity is not hidden or stigmatised among her friends—it is part of who she is, and it is embraced. Padma reflects on how outsiders do not see beauty in their slum, but she sees beauty in several aspects like the broken rooftops, the hanging saris, and the muddy streets.

Through these examples, Subramanian shows how the girls unsee the societal limitations imposed on them. They see discrimination, but they choose not to reproduce it.

Subramanian’s use of the narrative perspective of children in A People’s History of Heaven is a clever choice.

Subramanian’s use of the narrative perspective of children in A People’s History of Heaven is a clever choice. Their shifting voices provide innocent, yet insightful commentary on their lived realities. The girls are aware of their parents’ tolerances of injustices, but they consciously choose not to carry those biases forward. Their vision is clearer, simply because they do not accept the status quo as unchangeable. Their perspective invites readers to do the same, to question what they see and to challenge internalised biases.

A People’s History of Heaven is a powerful exploration of life on the margins, told through the eyes of those who live it. Along with narrating the story of five girls and a threatened settlement, it also challenges us to rethink the spaces we occupy and the biases we internalise. In doing so, it redefines what it means to see, and unsee, the world around us.

Through her novel, Mathangi Subramanian writes a counter-narrative to the stereotypical portrayals of girls from informal settlements. Instead of framing them as victims to be pitied, she shows them as girls who dream, love, support one another, and refuse to be silenced. It is a view of feminism that is collective and grounded, and of identity that is fluid and strong. In Heaven, we do not just find stories of survival; we find stories of joy, of resistance, of love, and of a future worth fighting for.

About the author(s)

Lakshmi Yazhini is a post graduate student, pursuing an Integrated Masters in Development Studies, at the Indian Institute of Technology Madras. Based in Chennai, Yazhini has an avid research interest in the intersectionality of feminist geography and the state, in peripheral cities. In her free time, she likes to bake, do yoga, read fiction and pen down her thoughts in her journal (which are most often about the micro inequalities around her). Yazhini hopes to explore, write and make a difference about these as a policymaker some day.