On 20th May, the Bengaluru police registered an FIR against unknows persons regarding a social media account sharing photographs of women passengers on Bengaluru’s metro without their consent. This occured following outrage on social media after the account amassing thousands of followers was brought to public attention.

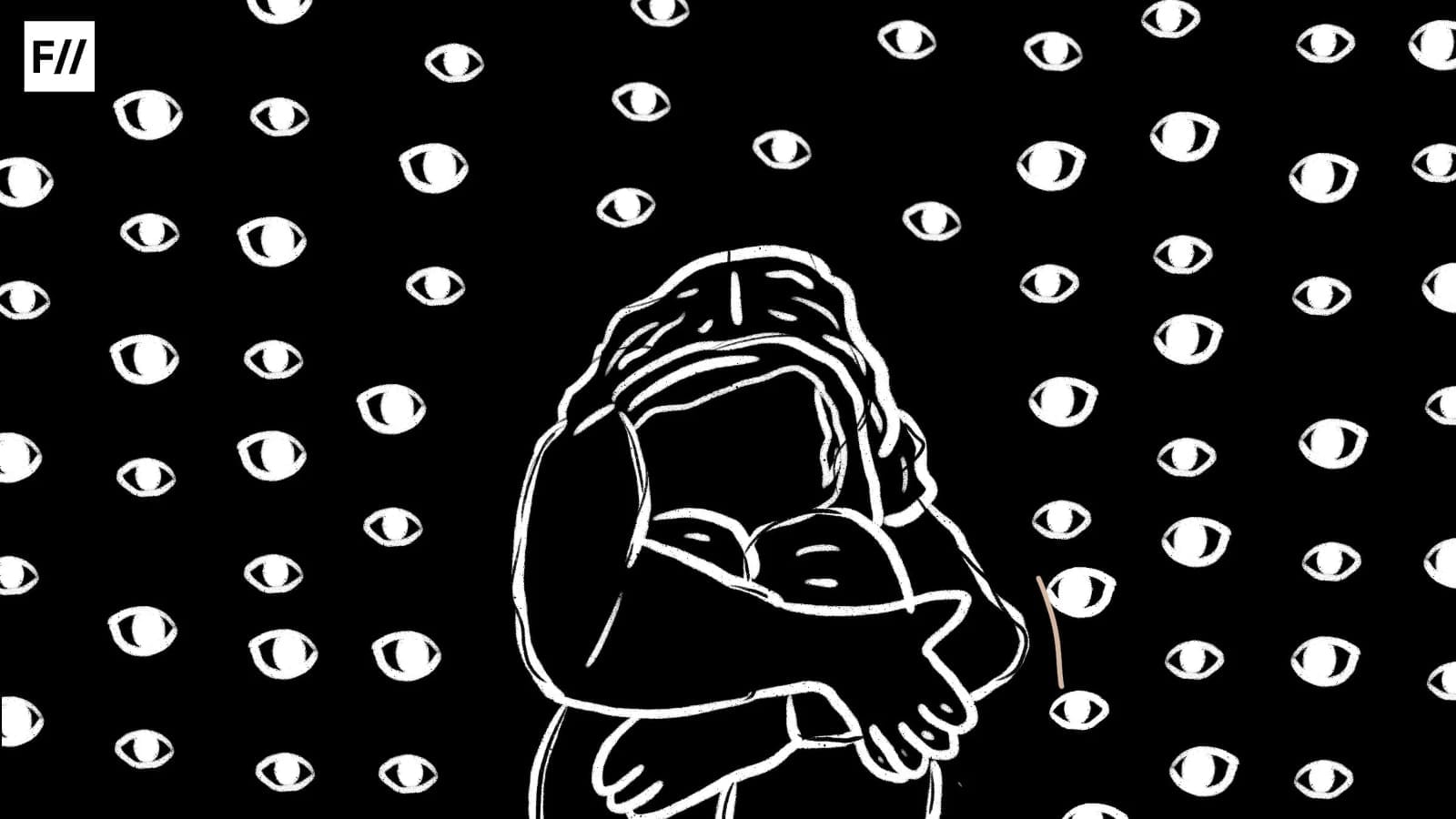

The incident has renewed concerns regarding safety of women in public spaces and brought forth debates regarding objectification of women, specifically in public spaces, and the question of consent. Resentment over the incident has also highlighted women’s long-standing struggle against patriarchal male gaze and its relentless pursuit to objectify women and their bodies across settings and has raised questions about women’s right to public spaces and freedom of mobility.

The incident

The Instagram account by the handle, @metro_chicks was brought to light when X user, Suraj Nair came across the account and brought it to the attention of the Bengaluru police and various Bengaluru based journalists in a call to action. The account, having more than five thousand followers had been secretly recording women passengers without their consent and uploading them on social media. The posts included objectifying shots and clips where women are being followed and filmed without their knowledge, and obscene captions and texts such as ‘finding beautiful girls on Namma metro‘.

The account was brought into the attention of the police only after the post by Mr. Nair triggered an uproar among X users. Following this, an FIR has been filed with Banashanakari police, South Bengaluru invoking sector Section 78 (stalking) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and Section 67 (publishing or transmitting obscene material in electronic form) of the IT Act.

The FIR has been invoked against an unknown person, however, the police has written to Meta seeking the identity of the perpetrator and is in the process of tracking down the IP address of the person running the account.

The incident, however is not a standalone case. It has followed a spate of such voyeuristic incidents across the country. Incidents of men taking pictures of women without their consent has recently surface across cities like Nagpur, Delhi, Chennai and Mumbai as well.

Incidents of women facing harassment in such public spaces is not new. In fact, reports suggest that more than 80% of women commuters have faced sexual harassment while using public transport in varying forms.

Incidents of women facing harassment in such public spaces is not new. In fact, reports suggest that more than 80% of women commuters have faced sexual harassment while using public transport in varying forms. Most women have reported feeling insecure while travelling publicly reflecting a profound lack of gender inclusive public transport system

However, the rise of social media, and widening of it’s user base across India, fueled by the widespread use of smartphones and the internet, has brought out new dimensions of harassment where non-consensual images of women can be easily circulated and accessed. The new digital age has provided perpetrators with unprecedented ease of access to personal content making it easier to exploit particularly women.

Further, the legal system has displayed significant shortcomings and lack of dynamicity when it comes to addressing the new forms of harassment that women face in the digital age the making women in public spaces more and more vulnerable to such forms of harassment

Women, public spaces and mobility: who has right to the city?

The incident is a manifestation of issues that arise within urban public spaces that are not gender inclusive. In fact, scholars such as Julia King have talked about how women’s feelings of unsafety impact their use of public spaces, and how urban design often fails to consider the needs of women and girls. Kristen Day has documented how women’s experiences in public spaces are shaped by their gender. Her work shows that women are more likely to have their personal space invaded and are more frequently touched or harassed in public than men. Using examples, she has documented how urban planning around the needs to men have led to marginalisation of the experiences of women in the city and restriction of their mobility.

Scholar Sanjukta Basu also talks about how safety concerns are compounded by the failure of local administrations to provide reliable public transport, well-lit streets, and responsive policing. Indeed, despite installed security cameras and other such safety provisions, the failure of administration to monitor perpetrators and understaffing has led to the failure of such measures in preventing harassment.

The spike in social media usage and it’s effect on women

As discussed earlier, the ease of access to social media as well as the anonymity provided by these platforms have made it easier for perpetrators to target women, leading to a sharp rise in both the prevalence and severity of online harassment. In fact, Social media platforms are identified as the most common venues for digital gender-based violence, including cyberstalking, hate speech, and non-consensual sharing of images. These acts create a culture of fear and insecurity, deterring women from accessing public spaces or participating in public life.

Threat of nonconsensual photo sharing through social media has emerged as a significantly new form of harassment. Research among adolescents found that 6.5% had their sexual images shared without consent at least once in their lives and about 74% of such victims are women.

In India, itself, almost 83% of urban Indian women have faced online harassment which includes unsolicited messages, lewd comments, non-consensual image sharing.

In India, itself, almost 83% of urban Indian women have faced online harassment which includes unsolicited messages, lewd comments, non-consensual image sharing.

Further, in tandem with internalised norms as well as increased visibility across such platforms, women are often reluctant to come forward due to fear of scrutiny or online public shaming.

Gaps in the legal system

One of the most concerning aspects of non-consensual image sharing is the lack of specific legislation to address this issue in India.

In India, voyeurism, the act of secretly watching a person in a private situation without their consent, is a crime under section 354C of the Indian Penal Code (IPC). However, the act is only limited to protecting privacy of women in private spaces. Further, a Kerala HC ruling in 2024 held that watching a woman and photographing her cannot be considered an act of voyeurism under section 354C of IPC. Thus, no specific laws exist to address sexual harassment through social media.

Further, the authorities treat such cases are reflective of violation of consent if treated within the legal premise. For example, the perpetrator has been booked under section 78 of the BNS for stalking rather than sections 75,77 etc. which elicit ore serious punitive measures. Acts like Information technology act, 2000 also falls short in addressing the complexities of violating privacy.

Legal remedies and policy interventions

Law is often the first deterrent. A comprehensive legal framework, addressing violation of women in public space specifically must be introduced. However, it is also true that the role of district level officials, their gender ideologies, and attitudes toward women play a crucial role in efficiency of such legal systems and the accessibility of women to such remedies. Thus gender sensitivity training across the board of officials, police officers, legislators and administrators is crucial to increase the efficiency of legal remedies and women’s access to them

Finally, urban cities can be redesigned to ensure safer mobility for women by integrating gender-responsive planning, improving infrastructure, and fostering inclusive decision-making.

About the author(s)

Sohalika Shrivastava is a 3rd year student at IIT Madras out and about to carve a niche for herself. In her free time she likes to read about and learn animal fact