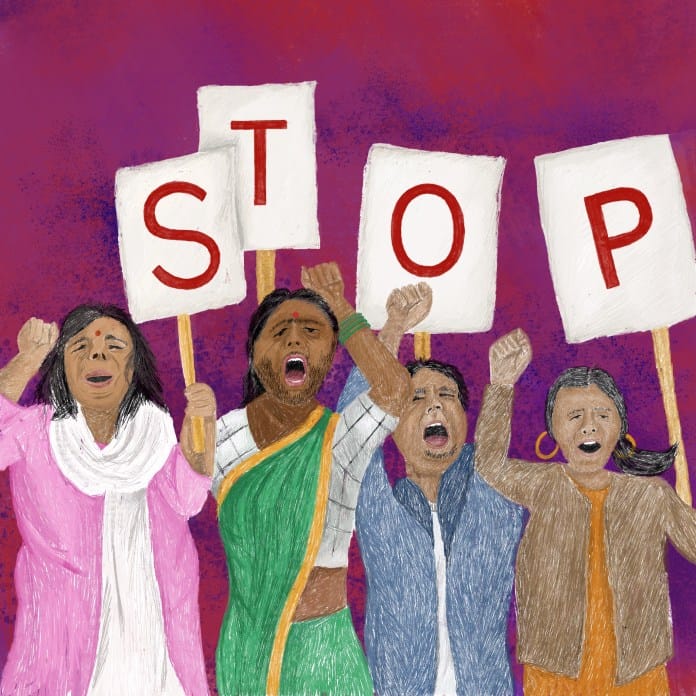

Are women’s issues just used as a weapon to get votes, or do people in power really care? Before we perceive the South Calcutta Law college rape case as another shocking incident, we need to talk about the larger rape culture that exists and affects every part of the society.

A pattern, not an exception

On 25th June 2025, a female student was gang-raped inside South Calcutta Law College. The four accused include an ex-student and non-teaching staff with previous political ties, two current students and the security guard allegedly on duty. This is not the first time such a crime occurred in a supposedly “safe” public space.

Last August, a trainee doctor at RG Kar Medical College was raped and murdered in a seminar room. Despite national protests and strikes by doctors and citizens, little has changed. This piece is a result of negotiating the same power dynamics, and knowing that no amount of awareness can keep us safe from the deeply gendered nature of institutional violence.

As Susan Brownmiller wrote in Against Our Will, rape is a conscious process of intimidation. It is not only the act itself but the fear it generates sustains gender hierarchies. Figures from the National Crime Records Bureau show that reported cases of rape in India have steadily risen since 2012. Yet conviction rates fluctuated between 27%-28% from 2018 to 2022 nationally. Bengal continues to feature prominently in the data, despite its reputation for relative safety.

What has changed, if anything, is the nature of violence. Perpetrators increasingly operate in spaces like colleges, hospitals, and homes, among others, that are considered safe. The illusion of safety has made it easier for institutions to avoid responsibility, even as violence intensifies.

The University Grants Commission (UGC) mandates every college to form an Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) and report sexual harassment data annually. But according to UGC records from 2022-23, out of 1472 universities and 45,000 colleges across the country, only 238 universities and 372 colleges submitted annual sexual harassment reports. Many do not constitute ICCs at all. In this landscape, their role often becomes performative.

Despite the legal mandate under the POSH Act, the failure of many institutions to constitute or publicise ICCs reflects a broader absence of gender-sensitive leadership.

Despite the legal mandate under the POSH Act, the failure of many institutions to constitute or publicise ICCs reflects a broader absence of gender-sensitive leadership. This order, like other government directives, appears to be limited to pen and paper. These laws and rules will remain mere formalities unless there is strict monitoring and punitive system.

Who gets believed? Respectability and blame in rape cases

Sara Ahmed, in her book Complaint!, argues that institutions are designed not to act, but to delay. Complaint becomes a slow, exhausting process that wears the complainant down. In such spaces, it is easier to withdraw. A 2022 survey found that only 15.7% of cases of harassment resulted in complaints. This silence is not passive but the notion of the “ideal victim” reinforces this.

After the South Calcutta Law College case, MLA Madan Mitra said, ‘If the girl had not gone alone, this wouldn’t have happened.‘ For the same incident, MP Kalyan Banerjee questioned, ‘If a friend rapes a friend, who can protect her?‘ These statements blaming the survivor reinforces the old cultural belief that only women who are modest, careful, weak and not alone can be seen as ideal and real victims. If a survivor fails to meet these expectations, the blame shifts to her. This is a form of symbolic violence. Bourdieu described it as the slow, invisible process by which social hierarchies are internalised.

MacKinnon argues that rape is not just about sexual violence, but about power and inequality. It is a way to maintain male dominance by using women’s bodies to remind them of their subordination. She shows how rape laws are shaped by the male perspective, where women’s consent is often assumed or ignored depending on their relationship to men.

In institutions already marked by hierarchies of caste, class, and gender, rape becomes a method of enforcing order and punishing those who step outside it. This reflects what feminist scholars describe as the ‘pedagogy of violence.’ Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality reminds us that survivors are not all treated the same. Violence against women is experienced differently based on caste, class, and community. If the survivor comes from a non-dominant background, her access to justice becomes even more precarious. Such cases, particularly, never receive attention or redress.

Reform, resistance, and the hope that follows

Debates on justice for rape cases often shift to demands for stricter laws or the death penalty. But legal reform alone can never affect how rape is understood or addressed. Scholars like Foucault have argued that defining rape as assault de-sexualises the act and may reduce stigma. But it also strips away the cultural context in which such violence occurs. As Smart and Helliwell have shown, rape is not just physical violence but is about shaming, silencing, and controlling.

As Smart and Helliwell have shown, rape is not just physical violence but is about shaming, silencing, and controlling.

Moreover, respectability politics continues to shape who are believed, protected, and perceived as “ideal victims.” This is why sexual violence persists even after protests, judgements, and reforms. Because the body and presence of the woman is still understood as the problem.

PM Modi’s vision of Viksit Bharat@2047 is for India to be a developed nation by 2047. As part of this vision, the Government of India’s Nari Shakti policy of women-led development is committed to improving women’s lives in the country but there has been limited success in India realising these goals for women’s empowerment. According to the World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report (2025) India ranks 131 out of 148 countries. Gendered violence remains endemic. If this does not change, India will struggle to meet the Sustainable Development Goals that depend so heavily on gender equity.

The absence of women in decision-making roles, even in fields where they constitute the majority, reflects a systemic erasure of female agency. In Indian medical colleges, while women now outnumber men in classrooms, their visibility sharply declines in leadership and boardroom positions. ICCs in educational spaces must be functional, independent, and accessible. Awareness sessions must go beyond tokenism. Faculty must not just be informed but also trained. And student voices must be prioritised. Safety cannot be built on surveillance by CCTVs or fear. It must emerge from trust, justice, and the dismantling of hierarchy. To resist this culture of silencing is to protect the idea of education itself, because if knowledge is power, then institutions that punish women for seeking either must be challenged. Long-term structural change, thus, requires interdisciplinary collaboration.