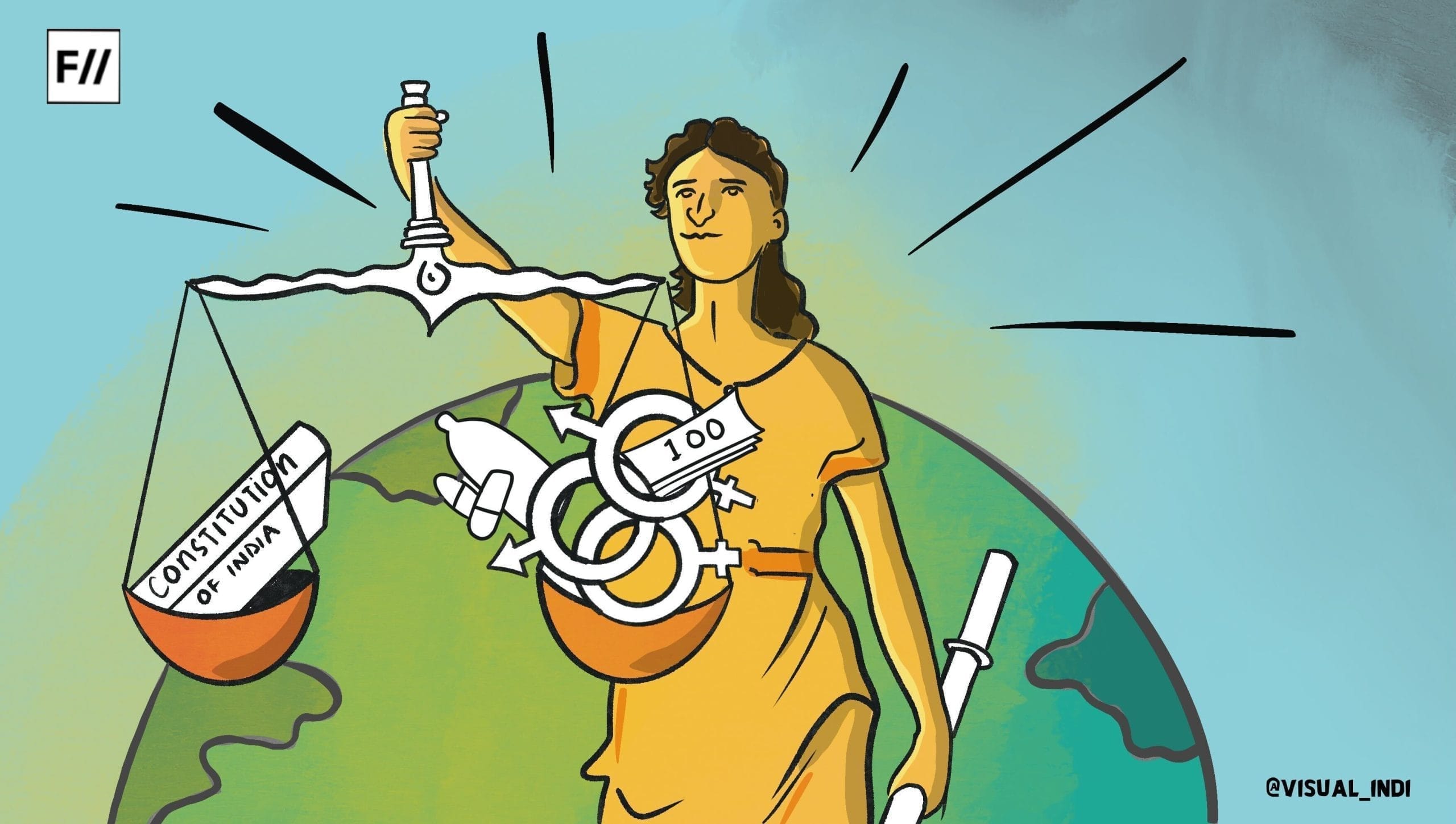

The Bombay High Court’s ruling in UNS Women Legal Association v. Bar Council of India & Ors. (PIL No. 16 of 2017, decided July 7, 2025) has caused ripples across the legal community, drawing attention not only for its immediate implications but for what it failed to engage with. At the heart of the matter was a straightforward but profound question: Does the Protection of Women from Sexual Harassment at Workplace Act, 2013 (POSH Act) apply to women advocates?

The Court’s answer—an emphatic no—rested on a narrow reading of the Act. The rationale: that since women advocates are not in an employer-employee relationship with the Bar Council or courts, they fall outside the scope of the POSH Act. But in taking this position, the Court overlooked the very architecture of the legislation, particularly the capacious and deliberate framing of its key terms.

Beyond employment: the POSH act’s expansive design

The POSH Act defines an ‘aggrieved woman‘ (Section 2(a)) as any woman, regardless of age or employment status, who alleges sexual harassment in connection with her work. The definition of ‘workplace‘ (Section 2(o)) includes not just conventional offices but also dwellings, unorganised sectors, and spaces visited in the course of employment.

The Act even provides for Local Complaints Committees (LCCs) to cover precisely those sectors where an employer-employee relationship does not exist. By this logic, a woman advocate who is self-employed, working in chambers, courts, or client meetings, falls well within the protective fabric of the statute.

The international lens: gendered harassment beyond contracts

Comparative jurisprudence from jurisdictions like the UK, Canada, and the EU reflects a broader view. The UK’s Equality Act, for instance, covers not just employees but also barristers and pupils, acknowledging the structural vulnerabilities of women in freelance or independent professions. The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits harassment in professional bodies, explicitly addressing harassment in legal and medical professions where formal employment ties are absent.

India’s international commitments under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) also mandate that states ensure protection against workplace harassment, irrespective of formal work arrangements.

The POSH Act was India’s legislative response to Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, which had laid down guidelines recognising workplace dignity as a constitutional right—not a contractual privilege.

The POSH Act was India’s legislative response to Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, which had laid down guidelines recognising workplace dignity as a constitutional right—not a contractual privilege.

The structural loophole in POSH: when independence becomes immunity

By relying on the absence of a formal employment tie, the High Court inadvertently weaponised the independence of the legal profession. The ruling suggests that because lawyers are self-governed and independent, they are exempt from mechanisms that protect dignity and safety. But professional autonomy should not come at the cost of accountability.

This leaves women in the legal profession—who already navigate entrenched sexism, casteism, and hierarchical power dynamics—without any formal redressal mechanism. Informal settlements, whispered warnings, and reputational risks are poor substitutes for structural protection. The judiciary’s unwillingness to read the Act purposively signals a retreat from the spirit of Vishaka and the constitutional right to a safe workplace.

What must be done: towards accountability in professional bodies

- Institutional POSH Mechanisms in Professional Bodies: Bar Councils and Court Bar Associations must be mandated by either judicial directive or legislative amendment to constitute Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs)

- Strengthen and Activate Local Complaints Committees: As per Section 6, every district must maintain a visible and functional LCC mechanism for women in unorganised or freelance sectors.

- Judicial Sensitisation and Interpretation: Courts must embrace a purposive and rights-based interpretation of the POSH Act, especially when dealing with structurally vulnerable professions like law, journalism, healthcare, and the arts.

- Amend POSH to Explicitly Name Professional Bodies: Parliament could consider amending the definition of ‘workplace‘ to explicitly include courts, chambers, and bar associations, mirroring global best practices.

- Independent Oversight: An ombudsperson or appellate mechanism should be established for complaints against ICCs or professional associations that fail in their duties.

Conclusion: a fork in the road

The UNS Women case should have been an opportunity to affirm the inclusiveness and moral clarity of the POSH Act. Instead, it has exposed the fragility of protections for women in independent professions. As more women enter the legal workforce and challenge legacy power structures, the law must evolve—not retreat. If courts and councils cannot offer shelter under POSH, then they risk sending a dangerous message: that professional prestige trumps personal dignity. It is time we chose better.

About the author(s)

Vanita is a lawyer by training and writes stories at the intersection of business & public policy, law, regulations and building inclusive workplaces. She is a Staff Writer for The Ken.