When we hear the word ‘evil’, imagine ‘evil’, or describe something or someone as ‘evil’, we often think of merciless, ruthless, barbaric or cruel perpetrators. We think of violence, dictators, hatred and atrocities. But for Hannah Arendt, it was the complete opposite. She saw evil in the ordinary.

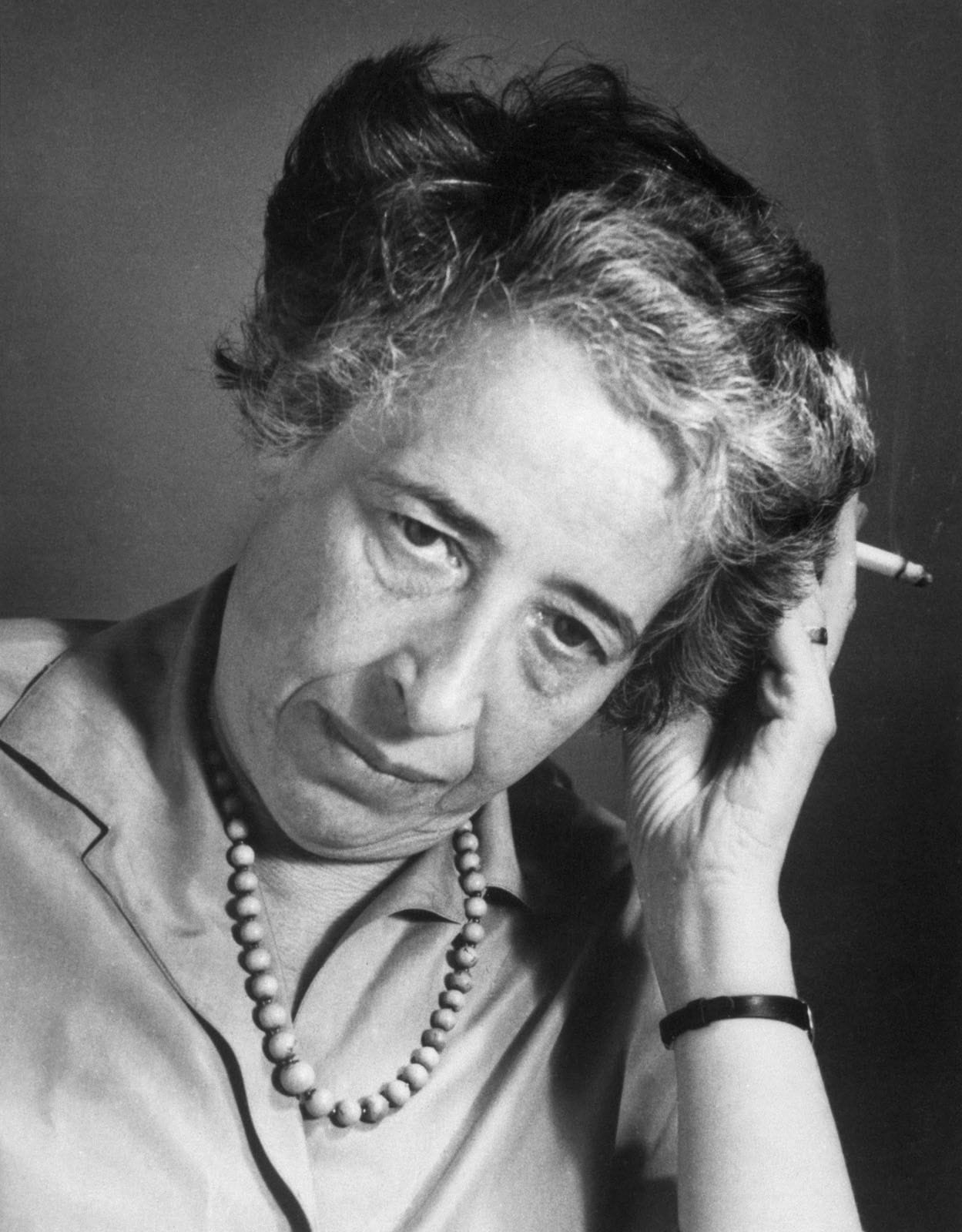

Hannah Arendt is one of the most influential political theorists of 20th century, born at the time of Nazi Germany into a Jewish family. Though she was not religious, merely carrying that identity had deeply impacted her life. Germany which was in a state of turmoil post World War I, saw the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party. It was marked by extreme forms of nationalism, expansionist wars, and systematic oppression of Jews and minorities. Minorities under Hitler’s regime were stripped of rights, subjected to physical violence and deep humiliation, and later deported to the concentration camps to carry out their genocide, which would later be known as the Holocaust.

To escape such a fate, Hannah Arendt fled Germany at the age of 27 for her safety.

What she had fled in her youth, she later confronted through the Trial of Adolf Eichmann – one of the chief architects of the Holocaust.

A trial in Jerusalem

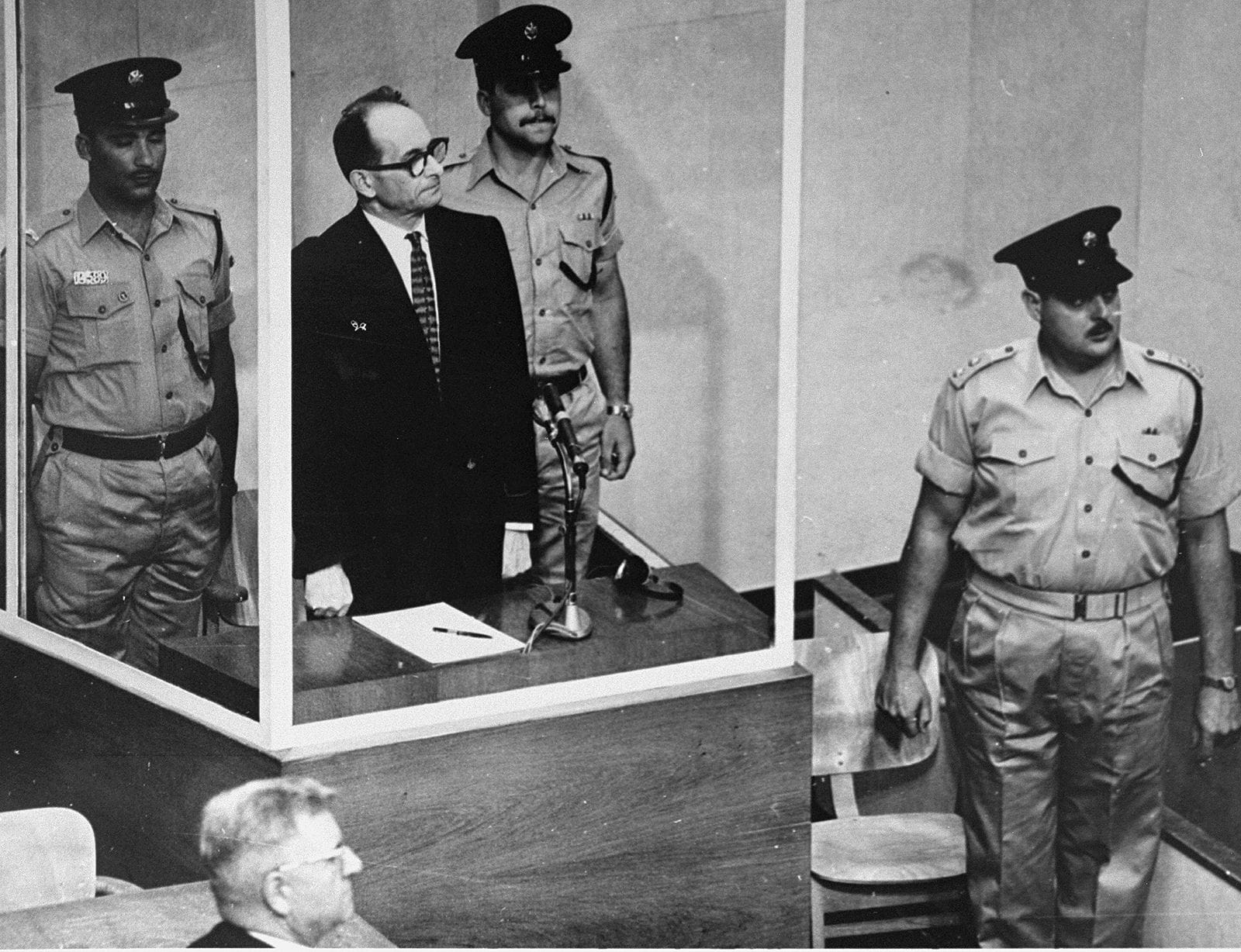

Adolf Eichmann started as a young officer in the Schutzstaffel, a powerful organisation in Nazi Germany, which later became one of the most feared arms of the regime. Within this system, Eichmann had rose to importance and became a high-ranking officer. He was in-charge of transporting millions of Jews across Europe to concentration camps. He made sure trains were running on schedule, that deportations never stopped and the machinery of such a system kept running in place.

Things changed post World War II. Leaders like Eichmann were held responsible for carrying out the Jewish genocide and holocaust, and were brought to trial in Jerusalem.

What came as a shock to the survivors was the demeanor of Adolf Eichmann. He appeared calm, he seemed mannered, and it was almost as if he was a part of the civil society existing ordinarily. When the world faces such a man, who had orchestrated such atrocity, they expect to see a raging and frightening man, full of hatred, but it was quite the opposite for Eichmann.

When the world faces such a man, who had orchestrated such atrocity, they expect to see a raging and frightening man, full of hatred, but it was quite the opposite for Eichmann.

He answered calmly to each allegation, and spoke in a tone which flowed like an ordinary conversation. He showed no guilt, no remorse but simply defended himself by saying he was just following an order. This was a man who had not thought of the consequences of his actions at all and for Hannah Arendt, who was covering his trial, his calmness and dullness led to the formulation of the concept of Banality of Evil.

Understanding the concept of banality of evil by Hannah Arendt

The word ‘Banal’ means to be obvious or boring. What Hannah means here, is that evil can look boringly normal.

Hannah observed that Eichmann had not viewed carrying out the Holocaust as something evil or morally wrong. To him, it was just another day at his job where he was carrying out orders. Through his justification, Hannah realised that how simple it was for an ordinary person to become a part of something evil. And this is what she calls the Banality of Evil – that one doesn’t need to be the embodiment of evil to commit evil acts but rather, ordinary people who cannot grasp the consequences of their actions are as much capable of carrying out evil acts.

She describes a state of thoughtlessness, where one cannot bother to think about or are simply unable to reflect whether their actions were right or wrong. Such thoughtlessness, to her, was the real threat to goodness.

Searching for relevance in the present day

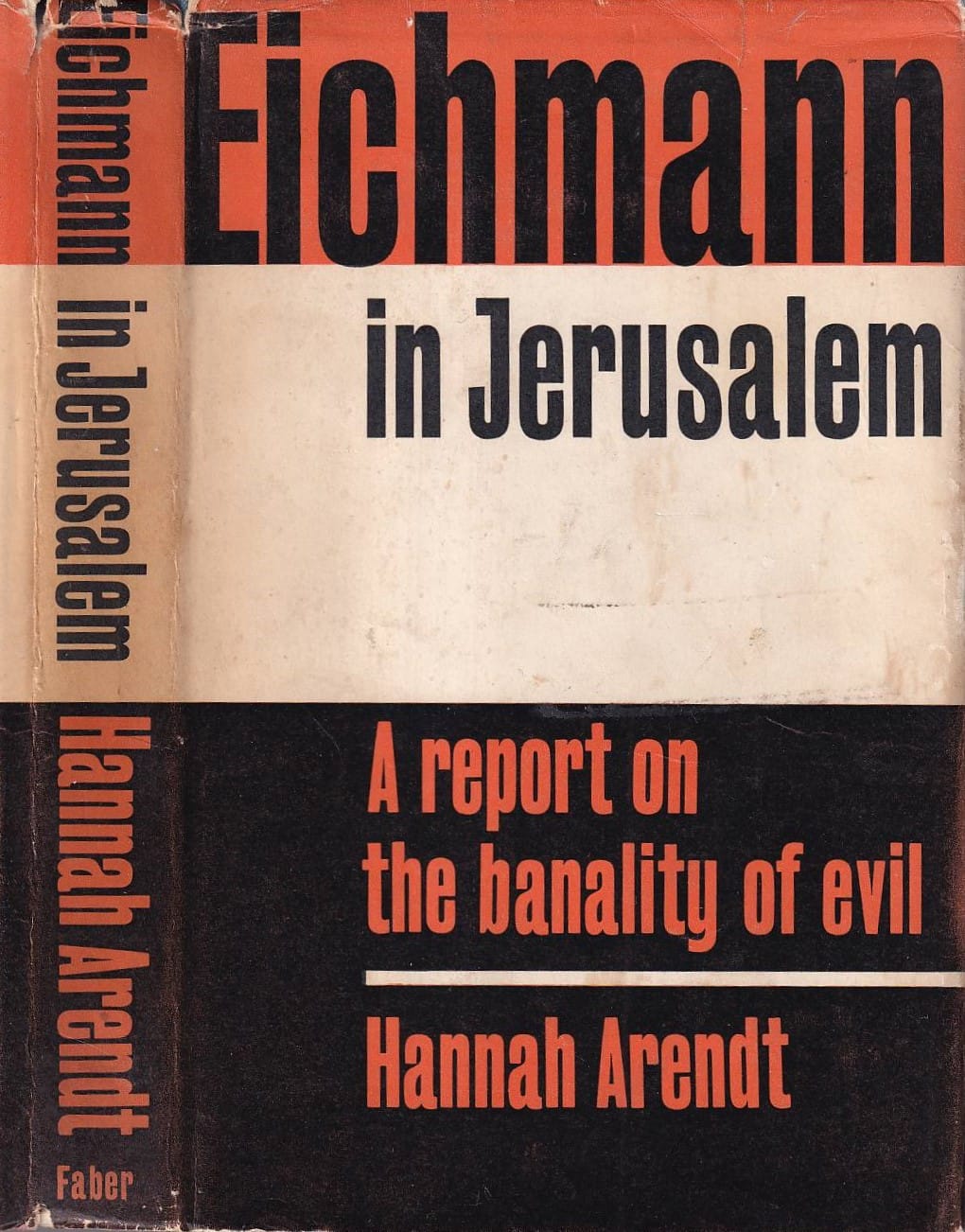

What was theorised in 1963 in the book Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the Banality of Evil is still relevant today in the year 2025.

In countries like Palestine, Rwanda, Myanmar and Yemen, genocides and ethnic cleansing are being carried out systematically for years, and it is quite unfortunate that it has become normalised.

In countries like Palestine, Rwanda, Myanmar and Yemen, genocides and ethnic cleansing are being carried out systematically for years, and it is quite unfortunate that it has become normalised. Authoritarian regimes have been on the rise and violations of human rights in conflicts like the Russia-Ukraine War are being reported on the daily.

Closer to home, the violence that took place in Manipur recently, has landed itself on the list of Genocide Watch – Countries at Risk.

When we look at the case of occupied Palestine, we see how occupation and control are sustained through administration and carefully orchestrated systems of permits, checkpoints, surveillance and ‘legal’ methods which make oppression and occupation appear justified. Beyond bureaucracy, military violence, silence of the international communities and dehumanisation of Palestinians are normalised, and treated as just an ordinary news which one just scrolls through.

Much like Adolf Eichmann, individuals involved in perpetuating such violence on Palestinians justify their actions on the grounds of national security, duties and policy enforcement. Justifications like these make grave violence appear as ordinary within the system, while the human consequence remain catastrophic.

The acts of violence committed on the victims in such a setting is exactly what Hannah Arendt pointed out. Ordinary people, who might just be your friend, colleague, neighbor, classmate if it weren’t for the situation, are the ones committing ethnic crimes and violence by turning to perpetrators. She argues that such people do not have a sense of morality but rather caught up in orders from higher ups. They don’t raise questions, or simply, dehumanise the ‘other’ side.

Hannah Arendt on Zionism as a Jew

The Guardian writes ‘Hannah Arendt would not qualify for the Hannah Arendt prize in Germany today‘ as she critiqued the foundation of the state of Israel and the Zionist Movement.

It is worth noting that Hannah Arendt doesn’t exactly fit into being a ‘pro-Palestinian’ or ‘pro-Israel’ in the way we use these terms today. She had supported Jewish presence in Palestine and a Bi-Nation theory, but she later became exceedingly critical of Zionism when it moved towards creating an exclusive Jewish state. She opined in her essay ‘Zionism Reconsidered’, that the creation of Israel, by displacing Arabs, would condemn Jews to a lifetime of conflict but does not advocate for Palestinians explicitly.

In ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’, Hannah wrote that while Jewish people have suffered enormously, their suffering should not justify new forms of injustice and oppression.

In ‘Eichmann in Jerusalem’, Hannah wrote that while Jewish people have suffered enormously, their suffering should not justify new forms of injustice and oppression. Her earlier stance on the creation of Bi-Nation seemed to have been scrapped, as she saw the Eichmann trial as a way to justify the establishment of a Jewish exclusive state of Israel, rather than focusing on bringing justice for the victims and survivors.

She notes that while Zionism was born of Jewish suffering, it might produce the same catastrophe it escaped while making those sufferings banal and ordinary – exactly how it is happening today.

The good and the evil

Hannah Arendt gives an interesting take on who’s evil and who commits evil in the theory of Banality of Evil. She explains that great atrocities like war crimes, genocides, ethnic cleansing are not always committed by inherently evil people but more than often by ‘normal’ individuals who do not think critically, do not have a personal sense of morality and surrender themselves to authority.

Evil is a result of immorality, obedience and thoughtlessness. And to her, this is the real threat to ‘goodness’ that everyone should fear.

About the author(s)

Mema is currently a Master's student at South Asian University (SAU). Hailing from Manipur, her lived experiences there have shaped a deep commitment to the feminist cause. She cares deeply about women and their future, which she tries to convey with her writing. She finds joy in reading, writing and cooking.