There is a dearth of superhero films featuring women, but Lokah Chapter 1: Chandra is here to change that. An entertaining, fast-paced, genre-subversive film, Lokah is refreshingly progressive and feminist in its politics. It’s not uncommon for superhero and horror films to provide social commentary; however, Lokah qualifies as social commentary wrapped in superhero and horror themes, and in the best way possible. While the film’s feminism is not perfect, the film is still a class apart from contemporary Indian films on similar themes.

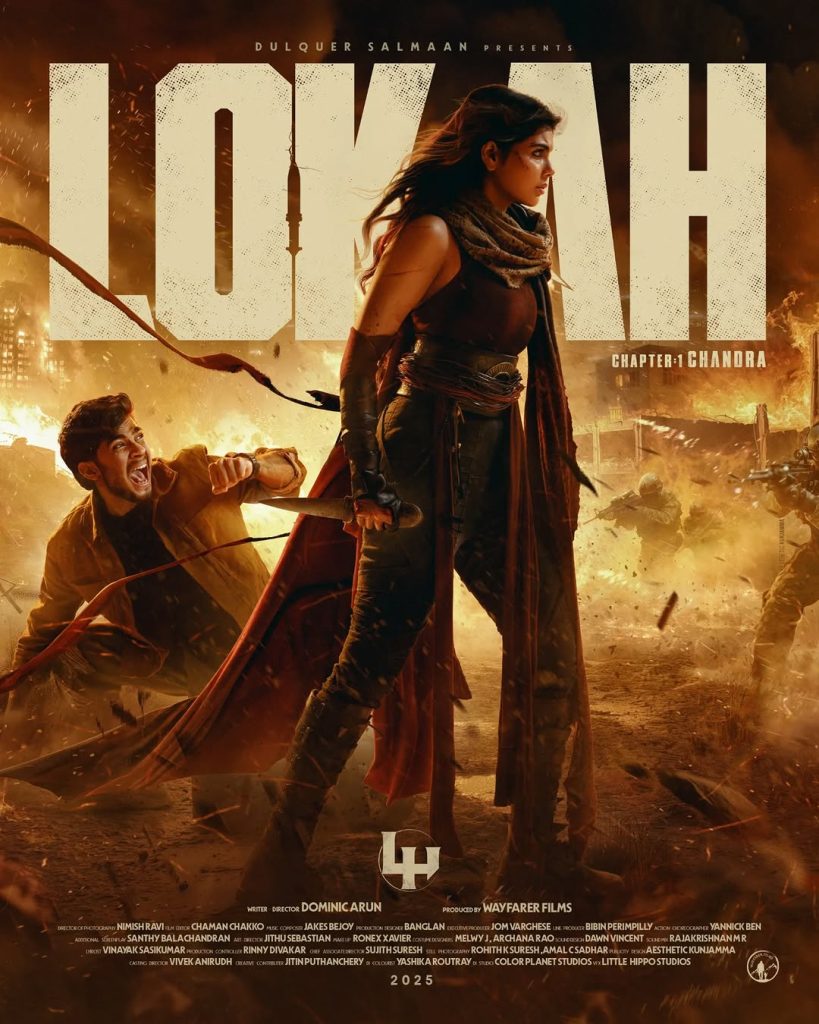

The film, starring Kalyani Priyadarshan and Naslen in lead roles, has been touted as the first Malayalam female superhero film. Priyadarshan plays a yakshi named Neeli (Chandra in the present day), and Naslen plays the unsuspecting Sunny, who accidentally witnesses Chandra’s supernatural abilities and is roped into a chase of cat and mouse alongside her when the duo draws the ire of crooked cop, Inspect Nachiyappa, played to perfection by Sandy Master.

The film has superheroes, action, suspense, social commentary, comedic moments, and horror elements. Lokah cannot be classed into one box or genre neatly, and that’s perhaps where it shines. In not trying to be one thing or confining itself to the limitations of one genre, Lokah leaves room for interpretation, allowing the viewer to take as much as they want from the film and leave the rest.

The myth of Kalliyankattu Neeli

Through a crisp retelling of the myth of Kalliyankattu Neeli, we learn that a young Neeli and members of her tribal community go into hiding to avoid retaliation by a despotic ruler after she and her friends enter a temple, breaking rigid caste rules. While in hiding, Neeli stumbles upon a headless female idol and is promptly bitten by a bat, gaining superhuman strength and speed and becoming immortal.

What follows is Neeli’s transformation into a being that’s part yakshi and part vampire, and an action-packed five minutes where Neeli takes on the king’s men and kills one after the other. By the end of the sequence, Neeli, now orphaned and feared by her community, goes on the run. This was centuries ago. Neeli, who now goes by Chandra, has spent her years since killing bad guys and has now arrived in Bangalore to investigate an organ trafficking ring.

The myth of Kalliyankattu Neeli is a folk tale about a yakshi (a nature spirit in Indian folklore) popular in Kerala. While the film uses the same name for Priyadarshan’s character, the backstory the film gives her isn’t true to the original. The legend, as told in Kerala, is about the daughter of a devadasi who marries a Brahmin priest and is then betrayed and killed because of this transgression of caste hierarchies, transforming her into a revenge-seeking, malevolent spirit. That Kalliyankattu Neeli is your more traditional yakshi; she seduces and lures men to their death. Priyadarshan’s Neeli is radically different. She’s no seductress or mindless in her rage. In fact, Neeli’s rage, which is always proportionate and never misdirected, exists alongside quite weariness.

Yakshis, vampires, and marginalisation

Marginalisation and the violence inflicted on the marginalised are significant themes in Lokah. The singular event that paved the way for Neeli’s transformation into the supernatural being that she is was when she and her friends, who are marginalised, defy the social and caste order that treats them as outcasts and dehumanises them. Young Neeli and her friends enter a temple that they were forbidden to enter. Upon being discovered, the king, who uses this temple for his private worship, unleashes his wrath on the community for violating regressive caste rules.

The choice to make Neeli a yakshi-vampire-like figure, as opposed to a regular superhero, is telling. Yakshis can be interpreted as a feminist figure; vampires have long been metaphors for marginalisation, exclusion, and the demonisation of the ‘other’. While traditional stories of yakshis position them as monsters or cautionary tales, yakshis have more autonomy or agency than the patriarchy affords ordinary women. They are also allowed to feel unbridled rage at the injustices they face, instead of being forced to suppress it by patriarchal societies that have no space for women’s anger. Yakshis don’t have to perform femininity for the patriarchy or play by its rules.

On the other hand, vampires are forced to live in the shadows. Unable to withstand daylight, they are not just forced to live on the margins of society but also out of its sight. Lokah features a scene in which Neeli and her friends hide behind a tree, watching the king offer his prayers at the temple from a distance. The king seems annoyed by this ‘intrusion’. Not only does he expect spatial segregation from the ‘othered’, but he also expects them to be invisible.

After the community is forced to go into hiding, they take refuge in a cave. While they are ultimately captured, this shadowy, lightless place is, for a brief period, their refuge from the violence awaiting them. In a way, then, Neeli has always been a vampire, long before she acquired supernatural powers. Like vampires, she was forced to live on the margins of society, in the shadows, expected to invisibilise herself. Yakshis, too, live on the margins, much like vampires. Neeli’s defiance of patriarchal and caste norms makes her a yakshi-like figure.

Living on the margins of society, however, also means the ability to sidestep its regressive social norms. They don’t have to play by the same rules of patriarchy, race, caste, or class. Which is why both yakshis and vampires are progressive, even feminist, figures: not only are they not bound by the regressive, exclusionary norms of regular society, but their very existence is a defiance of them. Vampires and yakshis in our folklore, oral traditions, literature, and media are not just adequate stand-ins for marginalisation, but also for the empowerment of the marginalised.

The evils of misogyny

Misogyny and its violence feature heavily in the film. Nachiyappa’s misogyny isn’t subtle or harmless. The first time we see him on-screen, he’s victim-blaming a woman who escapes organ-traffickers, asking questions of her and not the men menacingly stalking her. His anger is palpable when asked to salute his commanding officer, a woman. He strikes terror in his family by positioning himself as the head of the household after his father’s demise.

Nachiyappa is an egomaniacal, corrupt cop on the payroll of a local politician; however, the film is transparent in where his villainy truly lies: his misogyny. At a house party, as a coded warning to Neeli, he asks a male colleague to frisk a woman, relishing in her fear and discomfort. The decision to portray Nachiyappa’s character as a cop was astute. While this is essential to the plot, it also helps put his misogyny into context. The power Nachiyappa holds as a police officer makes his misogyny more menacing and a clear threat. When his misogyny spills over into his people-facing job, it’s clear for viewers to see how harmful his – and all – misogyny is.

However, the one area where Lokah disappoints is Sunny’s voyeurism, which is positioned as charming and harmless and played for laughs. Sunny and his friends spend a reasonable amount of time staring into Neeli’s window, attempting to befriend her when she makes it known she isn’t interested, and pining for her. Further, his friend Naijil’s (Arun Kurian) attempts to pursue Neeli are awkward and uncomfortable, serving no purpose. These moments seem to exist to provide comedic relief, but for a film that’s progressive and feminist in its portrayal of gender and misogyny, banking on voyeurism and awkward pining for the beautiful woman next door for laughs is a disappointment.

However, Lokah’s portrayal of a female superhero is praiseworthy because it doesn’t merely change the protagonist’s gender; instead, it flips the script and sets an example of what a good, nuanced, complex portrayal of a female superhero looks like. Neeli might be a vampire-yakshi-superhero figure, but there is also something deeply human about her. As out-there as her portrayal might be, she remains firmly relatable and sympathetic.

Neeli is not your regular superhero who borders on a vigilante or has the perfect moral code; she’s not sexualised or fetishised, and her powers and abilities are not aspirational. Essentially, she’s not a patchwork of superhero or horror tropes. Neeli is her own kind of superhero, vampire, or yakshi, what have you. This makes her unlike any character to grace our screens, making for a gratifying watch.

About the author(s)