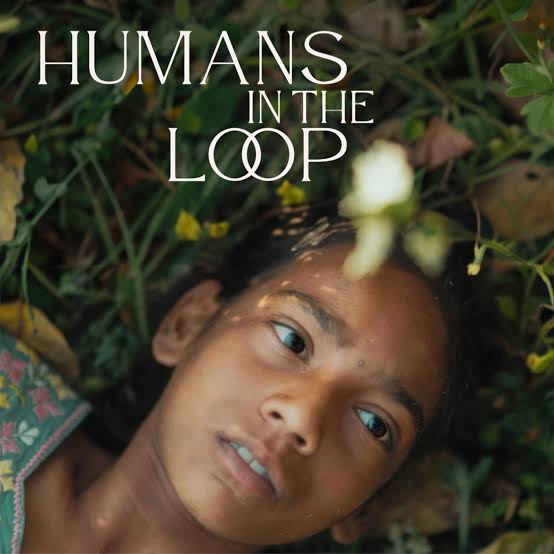

Humans In The Loop is a 2024 independent film which marks the directorial debut for Aranya Sahay. It is unlike any film about AI. This movie sings the songs of the unsung heroes, or rather, the unsung heroines of the artificial intelligence data centres in India. In just a matter of 72 minutes, i.e. little over an hour, the film explores the triumphs and perils associated with training AI and motherhood while also observing the gap between the task-oriented AI and environmentally sensitive regional communities.

The film is inspired by Karishma Mehrotra’s 2022 essay titled “Human Touch”, published on Fifty Two, which is about Human-in-the-Loop (HITL)—a term used in the IT sector for the human labour force directly and actively involved in the operation, supervision or decision-making of an automated system. These tasks involve and are not limited to what’s known as data annotation or data labelling, a task traditionally outsourced to third-world countries like India.

Humans In The Loop: a film that rewrites the invisible

This particular article traces the lives of the many women from underserved backgrounds performing the laborious yet crucial task of data annotation for American and European AI companies. These women have a direct hand at making the technology ‘intelligent’ while navigating their own lives full of prejudices. It is in this larger context that Humans in the Loop is set.

This movie sings the songs of the unsung heroes, or rather, the unsung heroines of the artificial intelligence data centres in India. In just a matter of 72 minutes, i.e. little over an hour, the film explores the triumphs and perils associated with training AI and motherhood while also observing the gap between the task-oriented AI and environmentally sensitive regional communities.

Tucked away from the hustle and bustle of the cities, Humans In The Loop is set in the village near Johna Falls in Jharkhand, beautifully captured by cinematographers Monica Tiwari and Harshit Sahni. The lush green landscape provides a much needed respite from the long hours women-in-the-loop spend in front of their computers, busily typing away, testing CAPTCHAs after CAPTCHAs and teaching AI models how to identify different parts of the human body.

The heart of the story revolves around fictional characters, a mother-daughter duo—Nehma and Dhaanu. Nehma (Sonal Madhushankar) is an Adivasi woman who belongs to the Oraon tribe and has two children from a Dhuku marriage system—a form of live-in marriage which is not legally recognised. Her older daughter Dhaanu (Ridhima Singh) is 12 years old and wants to live in Ranchi with her father (who belongs to the general caste and is about to marry someone in a traditional ceremony) while her younger one is just a year old toddler named Guntu. When the film opens, we find Nehma fighting for the full custody of her children, for which she joins an AI data centre near her village to prove her autonomy in providing for them.

The porcupine and the politics of labelling

Broken neatly into three chapters, we get an insight into how motherhood and data labelling for AI go hand in hand. The film beautifully personifies the AI model, which learns to stand, then to crawl, and by the end of it, to run, as more data is fed into the system.

The task of labelling pests for AI becomes a critical point of contention between Nehma and her supervisor. When the supervisor asks why a caterpillar has not been labelled as a pest, Nehma replies, “That’s not a pest, Madam. It does not harm the plants. I wanted to tell you during the presentation. It’s not a pest. It does not eat the leaves. But only the rotten bits. So that the rest of the plant survives. It does not harm the plants. AI is like a child. If you feed it wrong information, it will learn wrong things.”

With the support from her supervisor (Gita Guha), Nehma excels at being a mother to the AI; however, things at home suffer for it.

Back at home, Dhaanu joins a new school and struggles to make any friends. Unable to understand why her mother has trapped her in this village, she attempts to run away with Guntu on foot to Ranchi to be with her father. When lost in the forest with her baby brother, she comes face to face with a porcupine—an animal that used to visit her mother when she was younger.

AI is like a child. If you feed it wrong information, it will learn wrong things.

The flashes of the genteel animal are littered throughout the film and serve the purpose of showing us that Nehma and Dhaanu are cut from the same cloth and hold the same kind of quiet resilience to society and its made-up rules. The animal is highly misunderstood and even considered ‘dangerous’. However, the porcupine is actually an extremely shy creature; it has a docile nature and doesn’t attack unprompted. The porcupine ends up serving as the ‘guardian angel’ for the pair of siblings, proving that the bond with nature cannot be taught; it is rather nurtured and learned. Perhaps, it is all a matter of how we label things?

The turning point is when Nehma’s supervisor shows her the larger implications of the technology, something we are oh so familiar with: generative AI. When they search for images of beautiful tribal women from Jharkhand, the search result either throws them images of white women in Red Indian costumes or comes out empty, solidifying the gap between the West and us. Nehma feeds the system with photographs taken on the phone by Dhaanu and is able to log authentic data, teaching the AI to recognise people from her tribe, putting her community on the world map.

What’s striking is that Sahay is able to balance all these complicated themes solely on the shoulders of the mother and the daughter, with hardly any men holding any screen presence. Both the actors are charming and hold the attention of the viewers till the end. While the rest of the village keeps a distance, the camera zooms in on their faces, unafraid, breaking the invisible barriers of societal acceptance. The rift that begins between the mother and daughter at the start of the movie comes to a close with a heartfelt acceptance of each other.

In showing acceptance, their labels for each other change, helping them understand what may seem like a threat may not be labelled correctly. Nehma is not some Adivasi woman stuck in a Dhuku marriage; she is a mother who is trying to make ends meet for her children. She is an AI data labeller, a woman with agency and financial freedom to take care of her children. And Dhaanu is not some runaway kid; she is a good student, a good sister, and a good photographer and someone who braves the changes thrust upon her. In a sense, both of them break free from the world that likes to label roles neatly.

Humans in the Loop has won the Best Indian Film award at the Bengaluru International Film Festival (BIFFes) 2025 and has recently won the FIPRESCI India award—an honour it shared alongside Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light. The film has also officially entered the race for Oscars 2026. After its festival rounds all through 2024 and limited theatrical screenings, Humans in the Loop is finally available to watch on Netflix.

About the author(s)

Aarthi (she/they) is a young feminist, currently based out of Jodhpur, who enjoys writing on pop culture and art-related subjects. Through her writings, she attempts to position herself between self-reflection and social conversation leading to the exploration of unconventional ideas. In her free time, she travels, writes poetry, watches films and anime