My friend loves to rock high heels. At 5 feet and some few inches, she is preternaturally short, but her penchant for skyscraper heels has nothing to do with her height. She is a dancer who is fabulously proud of her ability to sashay around in 5-inch stilettos and tends to wear them whenever she can. High heels are the equivalent of comfort food for her. But my friend is also 26 years old, which puts her squarely in the middle of the ‘get-her-married-before-its-too-late age’ bracket.

At a strange family gathering (you can count on those to enhance your understanding of sexism), a distant uncle (you can count on them too, actually) remarked on her footwear. The general import of his commentary was that it made sense for her to wear heels because she’s short, and the heels were her shortcut to a tall-dark-handsome type of man. How my friend eviscerated the uncle after his unsolicited critique is not the point (although it might make for interesting retelling). What is important, however, is that he automatically presumed that only two factors motivated her choice of footwear – A) hiding the features that society considers are her deficiencies and B) snagging a man as if he were a trout.

Plenty has already been written about the sexist and post-feminist connotations around high heels. While it is claimed that they are a regressive manifestation of ridiculous and potentially harmful social standards of female beauty, it is also believed that heels are tools that help make women feel empowered. The debate rages on. Op-eds about the social compulsions that command women to brave high-heeled footwear abounded especially when Julia Roberts walked the red carpet barefoot. They became a raging issue when 27-year-old Londoner Nicola Thorp said that she had been denied employment because she showed up in ‘smart flat footwear’ instead of high-heeled shoes.

It is patently obvious that no woman ought to feel compelled to wear high-heeled footwear. But it is equally important that women ought not to be coerced out of heels either. It would be simplistic to assume that it is only the female choice which matters because our choices are often affected by sexist ideas of beauty or acceptability. It is essential to understand how much our choice of heels has to do with patriarchy (How do I internalize thee? Let me count the ways), but if a person (not essentially a cis-woman) knows why they are wearing heels, and what their choice is rooted in, heels can be pretty stupendously empowering. My friend would attest to that.

This incident threw me back to my childhood when I was firmly coached that high heels are the devil. “See how they make your butt jut out,” my grandmother admonished, prompting me to crane my neck unnaturally and see what they were doing to said butt. My adamant butt was unaffected because the heels were exactly 2 inches high.

My mother firmly believed that high heels are awful for the legs, posture and health (there is considerable evidence to prove that) and steered me away from the weapon-like ice pick heels. I grew up wearing mostly flat footwear and I was confident that heels would give me a nosebleed (not just because they put me at a substantially higher altitude, but also because of the very high probability that I would fall down face first).

When I entered college and saw a close friend embracing skyscraper heels with confident ease, I was tempted to try. She enthusiastically encouraged me to try her wedges. I was teetering precariously on borrowed heels when a friend advised nonchalantly: “Please don’t do this; you will break your butt or something.” As unflappably caustic as his advice was, it was almost prophetic. Although I never did break my butt or the vague ‘something’ that my friend warned me off, I fell down spectacularly while I was sporting 3-inch heels. When I rued my inability to carry off high-heeled footwear, I was told that I was tall enough and height-enhancers were superfluous.

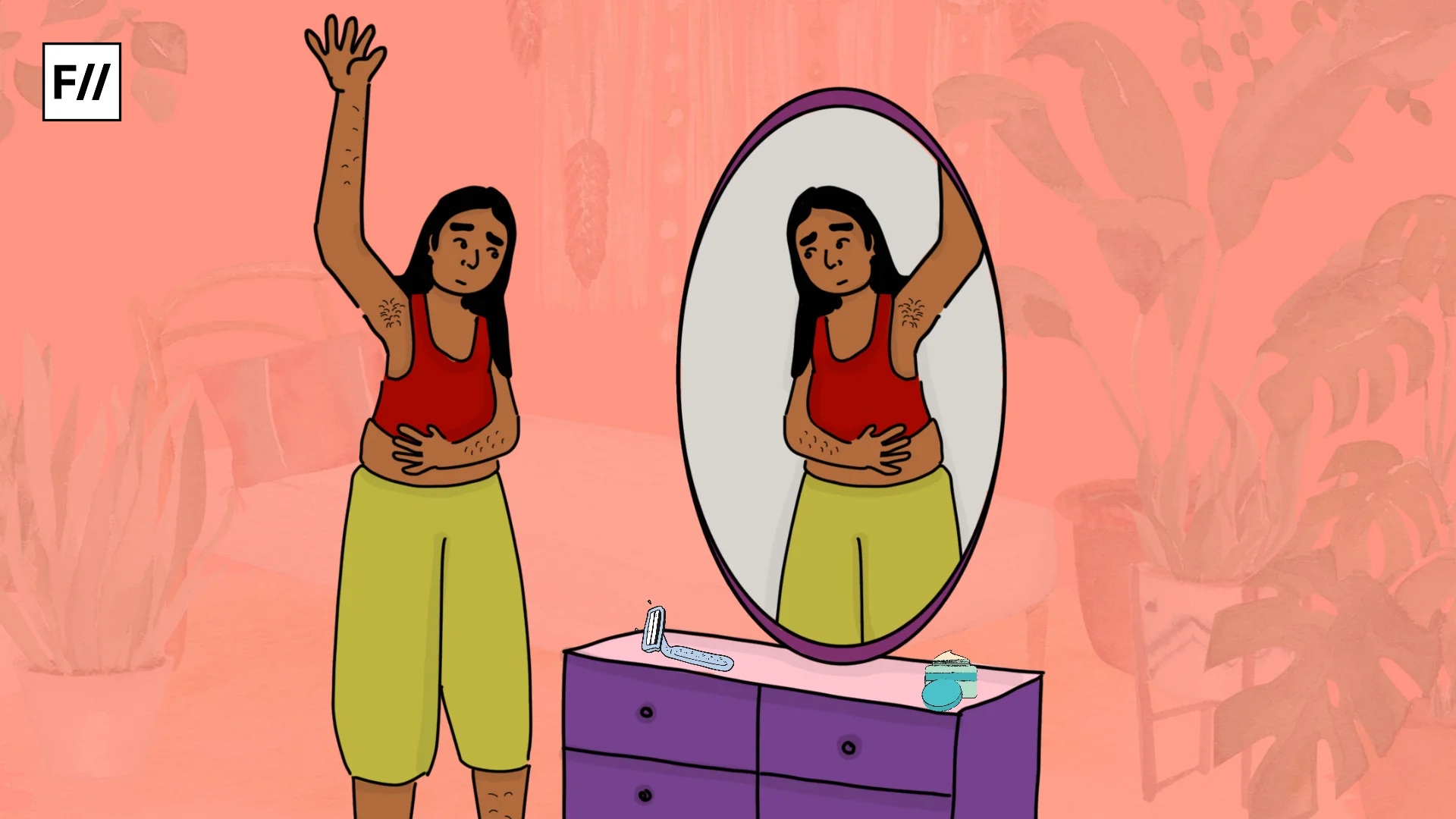

But women do not wear heels simply because they want to look taller. They are part of the armour women wear on a daily basis, like kajal or earrings, which are meant to make them feel confident and sharp. They are a part of our performance of femininity. They’ve not got as much to do with attracting men or confirming to social standards as they’ve got to do with personal preference.

My prosaic and practical choice of footwear (partially motivated by my battleship-sized feet) has often been the butt of several jokes. My friend’s gorgeous heels have been called impractical and harmful. Yet another friend is told not to wear heels around her husband because he’s shorter than her. My cis-male friend would love to wear high-heeled footwear, but doesn’t have access to the kind he fancies. The point is this: gendered and sexist notions enter several nooks and crevices, and they have also wound their way around our feet.

But no one can make you feel like a heel because of your choice of heels.

If I were to jettison awful puns, the bottom-line is this: If high-heeled footwear jibes with your idea of femininity (and feminism), and makes you feel strong and smart, you do you. And if you feel like it doesn’t, there is no cause for you to feel frumpy or inadequate in your beloved flats.

About the author(s)

Damini has recently acquired her post-graduate degree in Communication and Journalism from Mumbai University. Since she graduated, she has been engaged in research work and has presented papers at international conferences. Apart from pegging away at geeky (mostly feminist) literature, she has also conducted gender sensitization workshops. She is currently working as a news curator.